I am a physician, trained in pediatrics. I am also a black belt, trained in Tang Soo Do Moo Duk Kwan, a Korean martial arts discipline. While I have been a pediatrician for more than 20 years, I have only been a Black Belt since 2022. I am not one of those people who wanted to be a doctor since childhood, but I have always wanted to be a martial artist. What I did not appreciate until recently, however, is their philosophical relationship and the skills needed to be successful in both.

Doctors, starting in medical school, hear an enormous amount about the “art of medicine.” In a recent article, Dr. Jesse Shaw describes medicine as “the application of scientific data to treat disease” while art is more subjective, based on creative interpretation. He notes that perception of art is based on the lens of the viewer, influenced by personal events and life history.

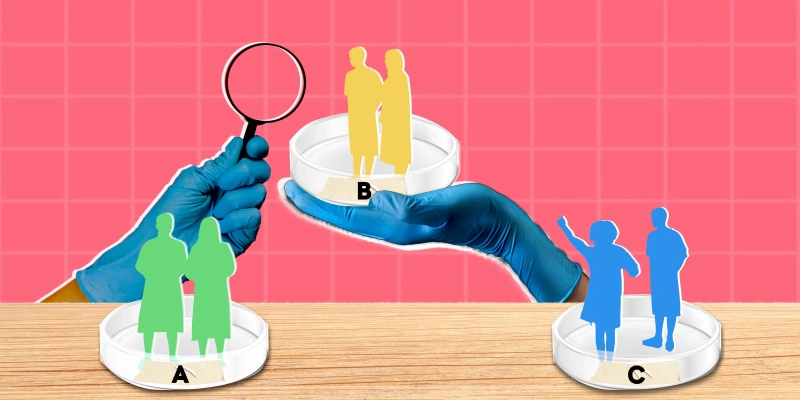

Dr. Shaw rejects the “art of medicine” concept, because he realizes, like I do, that it is often used a throwaway excuse for doing whatever you want for your patients, rather than using evidence-based standards of care. Through my martial arts training, however, I have come to realize that, just as the martial arts exist in the interface between mind and body that elevate them to an art separate from their military and self-defense applications, the “art” of medicine exists in the interface between science and humanism. We cannot separate our understanding of health and disease from the personal beliefs and frameworks that influence both.

One of my karate masters has a saying: To think outside the box, you must first build the box. Medical and martial arts training both begin in similar ways. In medical school, you start with anatomy and physiology, biochemistry and genetics, learning the building blocks which prepare you to study how these processes go wrong in disease. Similarly, in Tang Soo Do, you start with the basic forms, learning the techniques that establish muscle memory as the foundation for later skills.

Both martial arts and medicine have complex origins that can seem far removed from their modern practice, yet that evolution occurred very much by design. The East Asian martial arts use Zen Buddhist and Daoist philosophies to teach their practitioners to consider the physical and spiritual aspects of the self as one unit. Suspending rationality allows the body to react more immediately to its changing environment. This transition allowed skills originally designed for combat to evolve into a pathway toward self-development.

When I started medical school in 1995, the study of humanism in medicine was still in its infancy. The program at Yale University, for example, exposed students to art and literature to help build their skills in empathy, reflection, and psychosocial awareness. The skill of interpreting works of art, as the early adopters believed, would help medical students and residents to better describe what was happening with their patients. It would further help them to understand their patients’ own experience and interpretation of illness and disease. Thus, like martial arts, the art of medicine exists where the physician uses cultural competency to support, improve, or enhance patient health.

Pediatricians know that it is impossible to separate the art and science of medicine. Providing immunizations requires understanding the psychology of vaccine hesitancy. Family history and genetics influence the risk of hereditary diseases. Cultural beliefs underpin parental understanding of child development. Despite the complexity and importance of our role, however, pediatricians are gravely undervalued in health care. As a result, we are among the medical specialists most affected by moral injury and burnout, despite our (chosen) obligation to support the mental health of our patients.

I started martial arts training at a time when I needed an outlet for my own mental health challenges. I first tried yoga, which I enjoyed, but I struggled to turn off my mind while holding poses. In karate, I release my mind to develop pathways of muscle memory that maintain my focus and control. In an essay for the Association of Renaissance Martial Arts, author John Clements states, “… the activity goes beyond scientific application of effectiveness and into the realm of meeting the individual practitioner's motives and goals.” We each define the trinity of martial arts along the spectrum of our own needs.

When I am in the dojang, Dr. Clare disappears, and I become Mrs. Ticknor (it’s still all about the honorifics, after all), as much as those parts of my psyche are inseparable. Our Tang Soo Do student creed says, “I intend to use the skills I learned in class constructively and defensively, to help myself and my fellow man and never to be abusive or offensive.” That is awfully similar to an oath I first swore 25 years ago, when I received my Doctorate in Medicine: to help the sick, to abstain from their abuse or harm. The martial arts and the pediatrician unify to guide my patients and myself toward our healthiest futures.

How has your sports background helped you in medicine? Share in the comments.

Dr. Kimberly Clare is a pediatrician in Poughkeepsie, NY. She enjoys reading, crochet and the New York Times Sunday crossword but her real passion is karate (black belt in Tang Soo Do). Dr. Clare is a 2023–2024 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

Illustration by Diana Connolly