The dad sat heavily on the edge of his chair in the exam room, dropped his head into his hands, rubbed his reddened eyes and shook his head. “She just won’t sleep,” he explained of his bubbly toddler, who at the time of the appointment was jumping and climbing around the room. “It’s affecting the entire family. She turns on the lights to wake the other kids up, and if we take her to another room, she cries … something’s got to change.” He wanted an explanation, I wanted to make sure I didn’t fall behind with this being scheduled as a 15-minute appointment.

I can’t remember the exact words that I told this father or the exact plan I offered, but years later, I see it a bit differently when considering the empathy it may have lacked, coming from a young clinician without kids of her own. In retrospect, I had no underlying schema of being up all night with fussy babies, of balancing the demands of different family members with conflicting needs, of developmental regressions, of the feeling that you must be doing something terribly wrong as a parent, or else …

At the time, I probably thought this father was in fact doing something wrong. After all, my future kids, I assumed, would never (fill in the blank). A colleague I held in high esteem once offered that being a parent made him a better pediatrician, but it didn’t work the other way around. The statement, at the time, seemed like a conundrum: How could that be so? However, over many more years of pediatric care and raising my own kids, I think I’m closer to understanding it. There’s a big difference between approaching things through your head, and through your emotional experience. As a pediatric clinician, it’s only been through sleepless nights and what feels like never-ending temper tantrums with my kids at home that I’ve been better able to meet parents with the message that we’re in this together. Curiously, the reverse example of this logic rings somewhat dull.

I suspect many of us, as clinicians, have patients in our memory that when evaluating from the rearview mirror we would have said or done something a little differently. For me, for no particular reason, this patient is one that sticks out in my recollection. I wish I had a second chance to go back to this dad and say something different, or at least something more. Maybe my actual clinical plan would have been the same, maybe it would have been different. But most importantly, I would have approached it more from the position of “I’m on your team.”

The question becomes: How does this lesson translate to the rest of clinical practice? Is the answer for every clinician to have the same experiences as their patients: have kids, or have cancer, or be diagnosed with a chronic disease? Obviously not. The point is not that we go through the exact same things, but rather acknowledge that most of the diagnoses we make are in fact embedded in emotional journeys. There is no treatment plan to substitute for the need of our patients to tell their story and for the receiver to acknowledge that the story is hard, worrisome, annoying, confusing, etc. In an attempt to humanize medicine, we can remind ourselves that all these experiences are in many ways universal. Even if we haven’t experienced the same exact reality, we can offer “me too” in that we understand the prickliness of the emotions themselves. So, I propose adding a pause before jumping into a diagnosis and treatment plan:

Tell me more.

I want to hear about that.

What has this felt like to you, your loved ones, your friends, your colleagues?

What worries you about this?

So … decades later, here’s my revised attempt at meeting with a dad of a toddler who won’t sleep:

I nod my head emphatically and put my hand on his shoulder. “That is SO hard, I bet you’re absolutely, crazy exhausted. I remember that well!! Tell me what you’ve tried, tell me what’s going on at home, tell me how the other family members are reacting.” And then, I look at the toddler jumping around: “What do you think? Are you tired? Are you frustrated? Let’s all work together to figure this out.”

Today, I keep this patient’s encounter in my back pocket, to remind me in my day-to-day patient care to pay attention. When I see the signs of emotional struggle — the heavy eyes, the quivering voice, the shaking head — I aim to try and understand and acknowledge the described details of the experience. Hopefully then, when the patient leaves the clinic, they leave with a diagnosis, a clinical plan, and the feeling that someone else really cares about their story, whether or not they’ve lived it, too.

What have you learned from being a parent? Share in the comments.

Kyra is a pediatric NP who trained in Denver, CO and now works in a neighborhood community clinic in the Bay Area. She loves having the opportunity to interact with families and their community as a whole. In her free time, Kyra enjoys spending time with her two kids doing anything that requires being outside in nature. Kyra was a 2021–2022 Doximity Op-Med Fellow and continued as a 2022–2023 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

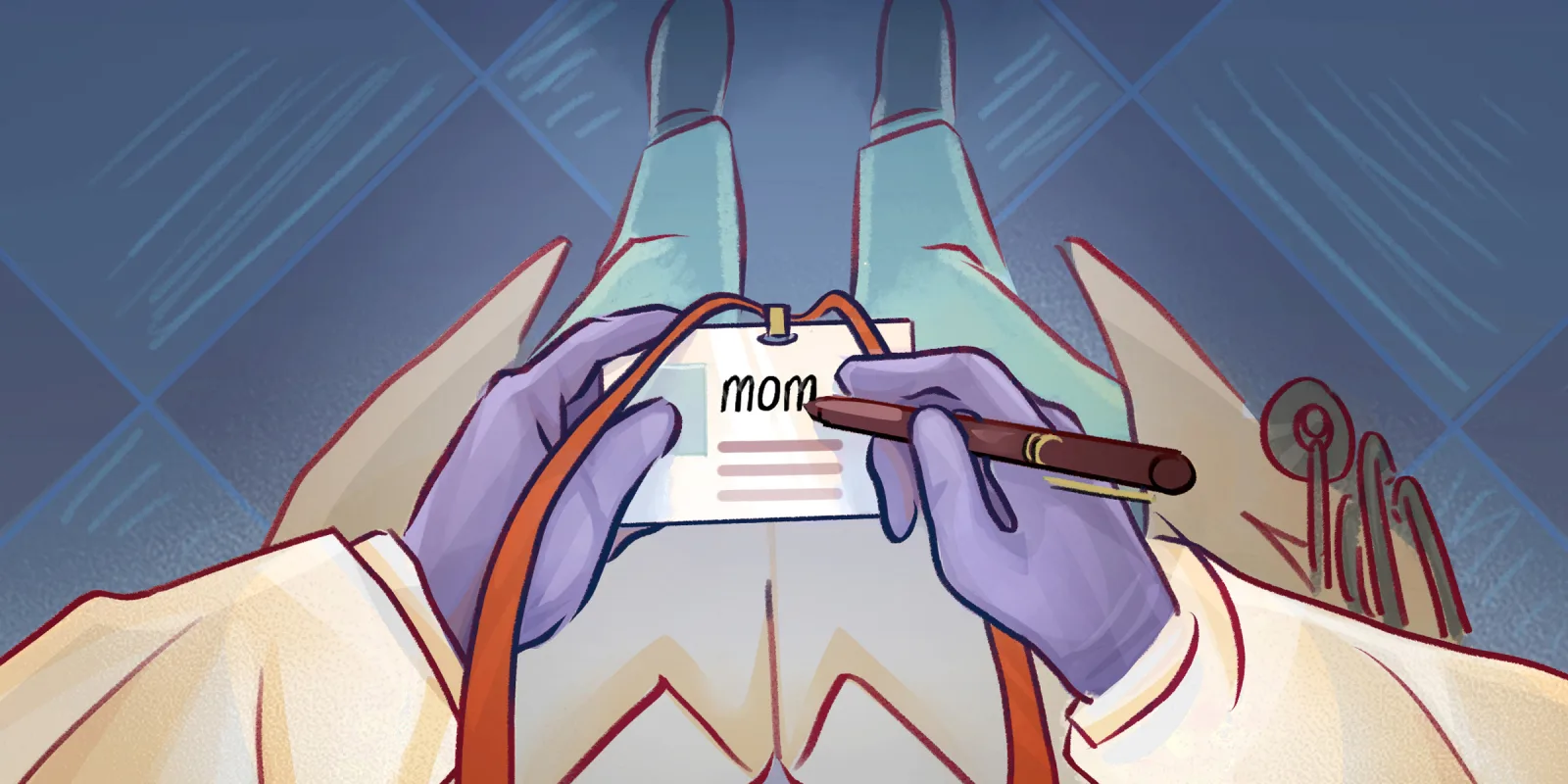

Illustration by April Brust