The summer of 2015 was the first time I fasted while away from home. I had three roommates and no kitchen. Huddled in the foyer of my dorm room, I quietly ate a banana, a pack of small chocolate chip muffins, and Stacy’s Pita Chips along with some hummus as my sehri, a predawn meal for Muslims fasting during Ramadan. I would pray, go to class, study, work on my papers, and break my fast with something from the dining hall. The novelty of fasting alone for Ramadan quickly wore off. I missed my family. This would be a recurring event over the next nine years as I fulfilled my premedical requirements, gained research experience, and crept toward a career in medicine.

Ramadan is one of the five pillars of Islam, a period of 30 days in which able-bodied Muslims fast from dawn to sunset and reflect on their purpose and relationship with God. In 2024, the first day of Ramadan in New York was on Monday, March 11 — the same day medical students across the world, including myself, found out whether or not they matched into a U.S. residency program.

I awoke at 4:30 a.m. that day along with the rest of my family, switching on the string lights and turning on the TV to watch ARY Digital’s “Shan-e-Ramazan” in the background. We ate, we prayed. And I refused to go back to sleep. Paralyzed, I could do nothing but anxiously wait for an email that would, for better or worse, change the trajectory of my life.

I matched. My mom cried. And at around 7 p.m. we broke our fast. No one could stomach the small slice of tiramisu that my dad had brought from my favorite bakery.

Then came the agonizingly long wait until Friday, March 15 at 12 p.m. In retrospect, the irony was obvious. Ramadan is a time of patience, introspection, and a call to improve one’s spiritual connection while maintaining a regular daily routine. And yet there I was, an impatient heretic, single-mindedly focused on another higher power who would deliver a message of great importance. This was it. My supposed “vocation.”

From my understanding, in Sunni Islam, there is no concept of “vocation” — a term originally rooted in Christian theology to refer to religious leaders or clergy who remove themselves from secular, everyday life and instead devote their time to serving God via the church. Even during Ramadan, the holiest month of the year, Muslims do not sequester themselves away from the world to focus on perfecting their religious knowledge. Rather, they strengthen their spiritual resolve ideally not only through prayer, but by facing everyday challenges head-on and engaging with the community to create positive change via charity and human connection. There should be no sense of superiority from one person to another, only a mutual effort toward understanding.

Perhaps that is why I have difficulty identifying my medical career with my “vocation.” Over time, society has come to associate the term with health care professionals, who are expected to remove themselves from their daily lives and serve the patient. Physicians are saviors, or heroes, dropping everything in order to help people in times of crisis. Indeed, as Sister Jane Dominic Laurel notes, physicians “[bind] themselves to a fundamentally altruistic ideal of service to others … and a reverence, gratitude, and responsibility for the specialized knowledge that has been entrusted to them” via the Hippocratic oath.

There is no denying that the practice of medicine and pastoral care are connected. Both medical and spiritual healers visit the dying patient, who receives not only care of the body, but also of the soul. Paul Kalanithi mentioned this link himself in his 2016 memoir “When Breath Becomes Air,” stating he “sought the pastoral role” through the practice of medicine.

While in medical school, I have heard educators and supervisors speak of the field with religious undertones to instill a sense of pride, accountability, and perhaps fear, into the hearts of medical students — emphasizing that their decisions as clinicians would impact patients in either the most beneficial or disastrous ways. “Technical excellence,” Kalanithi wrote, becomes a “moral requirement.” Such a mindset not only enacts the idea of medicine as vocation, but also centers physicians within patient narratives. Some view this concept as beneficial to the individual practice of physicians, allowing them to thrive via intrinsic motivation and ensuring a just future.

However, there are others who use this narrative of vocation for moral grandstanding. The blood, sweat, and tears — the suffering you experienced — to get to the point of being a physician must surely mean something, right? After all “rejoice and be glad, for your reward is great in heaven, for so they persecuted the prophets who were before you,” wrote the apostle Matthew. However, rather than providing introspection, the religiosity of medicine may pander to a false sense of moral entitlement and egoism among its devotees, thus limiting self and collective wellness in the field. Indeed, physicians found to have high, but fragile self-esteem were more likely to respond to subtle threats to their ego with greater defensiveness and “self-perceived invulnerability to conflicts of interest.” Such an outlook is bolstered by moral typecasting from the public and can in turn lead patients to hesitate to collaborate with their clinicians for fear of retribution. Both online and in person, I have also witnessed colleagues and superiors dismiss nurses, PAs, pharmacists, and others who question their medical decisions. Even among different specialties, physicians utilize religious language to challenge the word of others. “Surgeons are the god of doctors,” one attending said to me, “because we think differently.”

Nowadays, physicians are more willing to disentangle themselves from the term vocation, challenging the value tied to physician identity and relegating their work to simply a job. The reasons as to why are varied. Some wish to push back against the insurmountable expectations of care from the medical community and patients. Others see no value in the term when the health care system as a whole is not conducive to care.

As an incoming PGY1, I wonder about my own relationship to the field. Like the nuns and priests who live and serve in their house of God, so too shall I eat, sleep, and breathe within the walls of a hospital. And already I feel a sense of guilt, shame, and distress at my inability to know all. However, today, as I break my fast anew, I know it is neither my job nor my right to know all. Rather, it is through the unknown that I recognize my duty to work with others for the benefit of both patient and clinician.

How do you view the intersection of medicine and religion? Share your experiences below.

Soubhana Asif, MS is a medical anthropologist and fourth-year medical student at New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine. Her interests include community psychiatry, cross-cultural practice, and racial justice. She is a 2023-2024 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

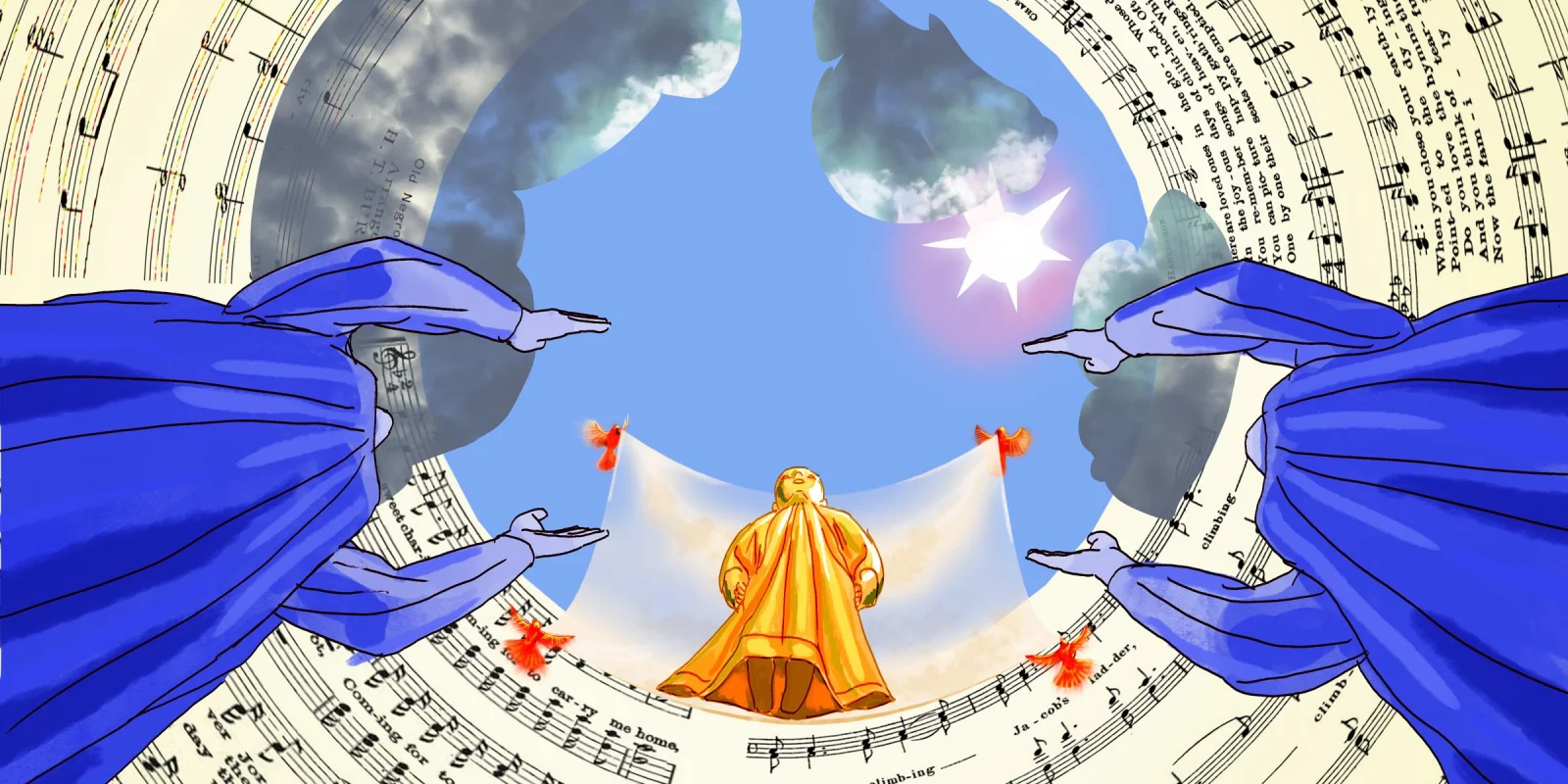

Illustration by Jennifer Bogartz