“This is a 17-year-old boy who came in as a category 1 trauma yesterday for a rollover MVC with bilateral uncal herniation, epidural hematoma and subdural hematoma currently intubated and sedated with propofol and fentanyl.”

As the overnight resident presented this patient on PICU, we could clearly see everyone’s bright early morning smiles fading slowly and starting to understand the grave consequences that were anticipated in this severe traumatic brain injury. We could see the wheels churning in the doctors’ brain, emotions churning in parents’ minds and tears pricking at the eyes in the rest of the family. Family understood how severe this injury was, but they kept saying, “We are hopeful.”

In the upcoming days, we would talk about the numbers and adjustments we would want to do that day. We would talk about how many boluses of the sedative he needed. We would talk about his central DI, terrible gases that he had and various ventilator settings we wanted in order to correct for those numbers. Then we would translate everything to the parents. We would tell them that we needed to decrease his metabolic needs and give as much oxygen as possible to his brain. Eventually we would ask, “Is there anything else that we can do?” Every time we would hear, “You can’t give me the one thing that I want and that is to bring my son back.”

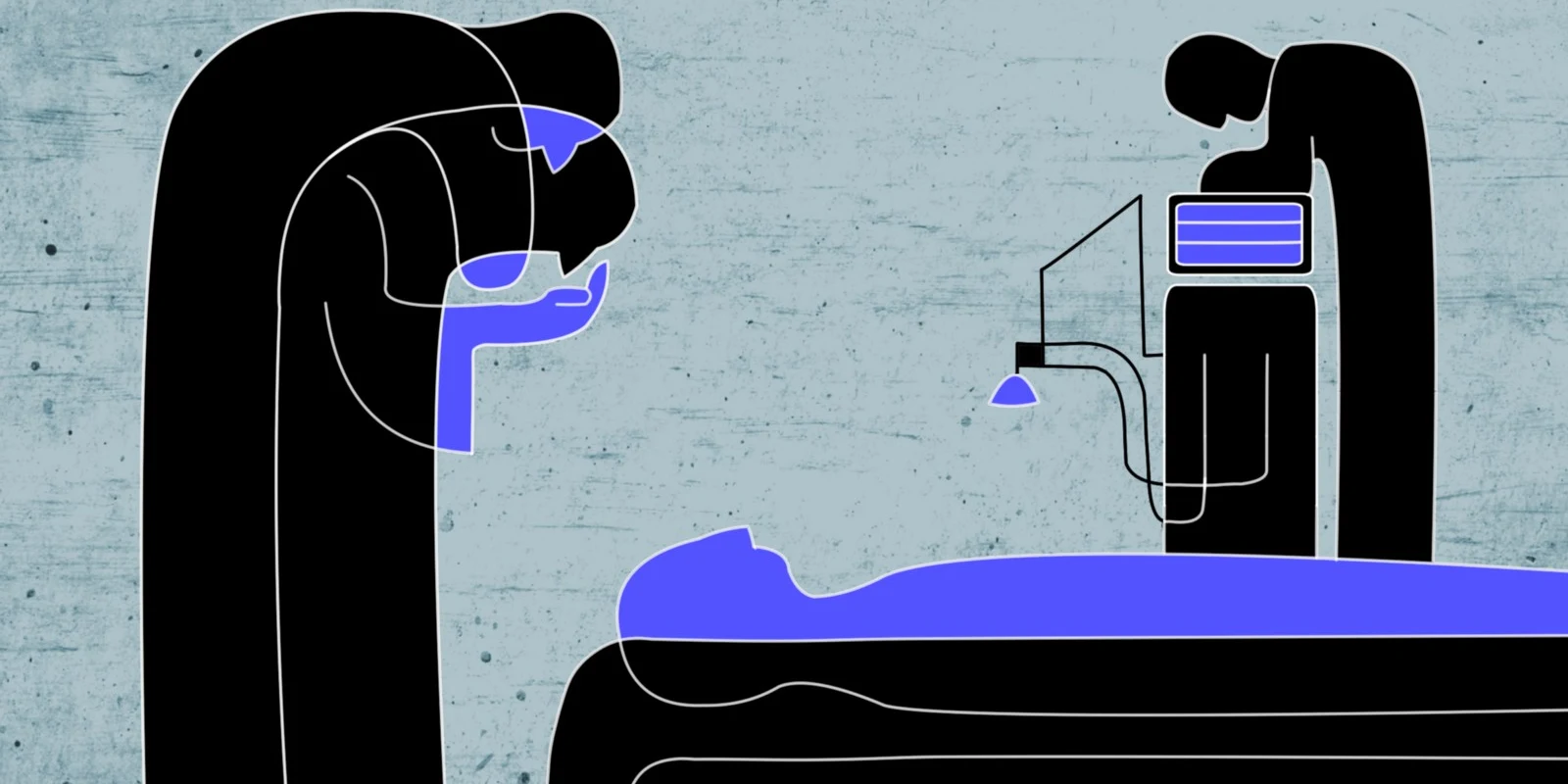

His central DI eventually resolved. His epidural hematoma was eventually drained by neurosurgery, although reluctantly. His requirement of sedation medication worsened. Now he was on 4 drips to minimize any extra energy expenditure that could worsen his numbers. He had a monitor placed in his skull to measure pressure inside the brain. Medically, there was no change in his outcome as his pressures continued to show worsening signs of brain injury.

Over the course of the next week, we saw the family, a few of them driving from faraway places. We saw his grandfather balling his eyes out, “He had his whole life ahead of him. Why him and not me?” he would ask every time. We saw his girlfriend, by his bedside, for the majority of the day, shocked and quietly looking for any changes in his breathing pattern. We saw his mother, running in from her bed sofa, hoping for a miracle with every beep of his ventilator or ICP bolt.

The attendings would lead multiple discussions with the families, privately, about withdrawal of care. We would talk, multiple times, about needing compressions or shocks to keep his heart alive. All these meetings would end with “We are still hopeful. Our son is a fighter. He will survive this.”

As the week progressed, I kept seeing his “normal” photos. They made him a collage with lots of happy faces with friends, family and feline. I grew fond of this family and was proud of them to show their sick son that he was loved and supported.

10 days and multiple drips of propofol, fentanyl, rocuronium, versed and vasopressin drips later, he was noted to have a perfusion pressure of 30. His heart rate was in 30s. His ICP bolt kept beeping when it read 30s. This was an uncharted territory for me. Being a pediatrics resident, I was lucky to not face so many deaths in my short career of 1.25 years. However, here I was, frequently bringing up words like “devastating outcomes,” “neurologically impaired,” “severe brain bleed” in front of parents.

Finally the day (or night) came. I was on a PICU 24 hr shift and I knew that he would either pass away or be very close to it by the end of that shift. That evening, I had a chance to seriously sit down with the parents. I asked them the uncomfortable questions, looking for comfortable answers about doing uncomfortable things to their son’s body to keep him alive. We talked, at length, about chest compressions, shocking, or emergency airways. As I continued to talk about these things, I could not help but tear up a little. I could not help but notice that in their agonizing questions was the undertone of their child’s survival. We made a decision that tomorrow we would withdraw all his support and extubate him.

“So are we good for the night?” his dad asked me about 30 minutes after that conversation. He seemed distraught, but tried to keep a strong face in this situation. Mom, obviously overwhelmed emotionally and fatigued mentally just nodded and smiled as I talked with them. I told them that I did not expect anything to happen overnight as long as he was on these medicines and as long as he was sedated. Then I saw his dad, agonizing over writing his home phone number on the board in case they needed to be contacted.

That was the moment when I could no longer hold back my tears. Here was a dad, just like how he had done all his life, making sure that his child was well taken care of. We had known his phone number ever since his son was admitted, however, here was a patriarch doing everything in his power to make sure his son’s caretakers knew how to reach him. That reminded me of my own dad trying to make sure that my chemistry teacher knew that I was weak in organic chemistry.

The next day, when I was supposed to be off, I continued to “stalk his chart” to see where he was progressing. After hitting refresh, I came across the attending note. Time of death: 1632.

Working with, or against death, is part of our lives in the hospital. Providers also go through 5 stages of grief when they know the severe outcome. However devastating these experiences are, they are important as a resident. These experiences are constant reminders about why parents do what they do to make sure their young ones are cared for, even though they might be breathing their last few breaths.

Dr. Shubham Bakshi is a 2nd year pediatrics resident at Baystate Medical Center. He finished his medical school from Northeast Ohio Medical University.