As I scanned items at my local grocery store self-checkout counter, I was reminded that every item has a Universal Product Code (UPC), consisting of a bar code and 12-digit number. In much the same way, procedures and services in the health care system have associated codes that form the basis for payment and reimbursement for services rendered in the modern health care system. The American Medical Association’s (AMA) Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) is the most widely accepted medical nomenclature in the U.S. CPT codes are used to identify professional services and to report those services in a way that can be universally understood by institutions, private and government payers, and researchers. While there are general guidelines about how to code for services, there is huge variability among practitioners in coding for services and little formal instruction about what is appropriate.

The AMA first published CPT terminology in 1966. By 1983, CPT was adopted as part of the CMS Health care Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS), cementing this system as the most widely used and accepted procedural nomenclature in American health care. CPT codes are now updated annually by the CPT Editorial Panel, an “independent group of expert volunteers representing various sectors of the health care industry” that is appointed by the AMA Board of Trustees. CPT codes are used for processing billing, payment, and claims, conducting research, evaluating health care utilization, and developing medical guidelines and other forms of health care documentation. Additionally, CPT codes play a critical role in the creation and adoption of new medical devices and procedural techniques. Without an applicable CPT code for a new device or procedure, a practitioner cannot bill or be reimbursed for that work. Numerous novel medical devices have failed transition to market due to lack of an associated CPT code, and this becomes a critical consideration for companies looking to successfully bring new innovations to market.

Despite functioning as a widely used, “universal” coding system, there is enormous variability in coding practices among surgeons and proceduralists across the country. Practices vary widely depending on practice environment, practitioner familiarity and training, region, medical specialty, and more. Procedural coding is at the discretion of the practitioner, and of billing/claims specialists that comb through procedural documentation to process and send claims to insurances. While there are general guidelines about how to code for services, there is little formal training in coding and most learn on the job. This is surprising given that these codes form the basis for payment and reimbursement.

As a resident physician, I am the first to admit that I have limited experience with the nuances of procedural coding. Yet as I start to learn more about this aspect of health care in preparation for practice, I have been surprised by what I’ve seen. I often retrospectively review operative notes dictated by attendings, as I find this helps me better understand procedures and helps in crafting my own operative dictations. At our academic medical center, some attendings include CPT codes in their operative reports, which I have found both informative and confusing. For example, I have performed exactly the same procedure with two different clinicians and seen a vastly different list of CPT codes for that procedure. One clinician may claim only 30520 for septoplasty. The next may claim 30520, 30802, 30200, 30930, 30465, and 64440 for seemingly the same procedure and add a “complexity modifier” which states the case was above average complexity. Of course, there are additional layers of oversight that determine which of these codes will actually be claimed and subsequently reimbursed by the insurer. Yet the difference between a minimalist and maximalist approach to coding can be stark and lead to huge financial and productivity discrepancies over the course of a career.

Coding practices can have huge implications on the cost of health care and the earning potential of physicians. As illustrated above, CPT codes dictate payment for services in health care. Beyond this, CPT codes are directly correlated with RVUs, which are used to adjust physician compensation and quantify clinical productivity, and can affect career promotion, salary, and bonuses. The “fee-for-service” model in American health care, which incentivizes doing things to patients, is intimately associated with procedural coding. This is one reason some hospital systems have tried to unbundle clinical “productivity” from salary. Coding differences also lead to disparities in payment. A simple, routine 4-hour sinus procedure can be assigned a value 3-4 times that of a difficult, complex 4-hour oncologic resection, due to differences in coding and reimbursement. These sorts of discrepancies are a key reason why some sub-specialties are particularly lucrative.

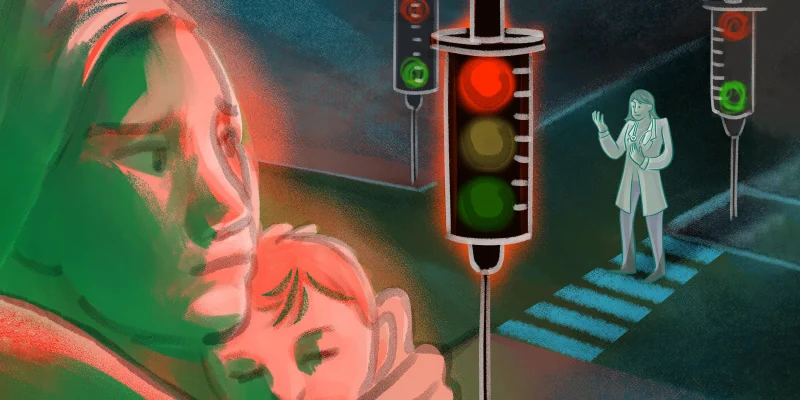

Given all these intricacies, coding can be ethically complex. There are significant incentives for practitioners to code aggressively. Yet should all physicians code to maximize their reimbursement? At what point does it cross the line to apply a certain collection of codes to a procedure, or to add on a nerve block or an endoscopy not because a patient really needs it, but because they might just benefit from it and doing so will increase payment and RVUs? Audits and insurance reimbursement denials can occur, but this is highly variable.

As I’ve moved through surgical training, the importance of understanding the nuances of procedural coding has come to light. Differences in CPT coding among practitioners can have huge implications for all parties involved. Despite this, best practices remain somewhat of a mystery. Additional education and training about procedural coding would likely decrease variability and improve equitability in physician reimbursement. Until then, I’ll relish in the simplicity of scanning the UPC code for a carton of eggs at the cash register and knowing exactly what I am purchasing and how much it will cost me.

What are your thoughts on CPT codes? Share in the comments.

Dr. Benjamin Ostrander is a current otolaryngology resident at UC San Diego. He loves beach days, long bike rides, cooking elaborate recipes, and playing music. Ben is passionate about art and design, creativity, surgical innovation, and global health. Ben is a 2021–2022 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

Image by UnitoneVector / Getty