A Poem & Conversation With David Watts, MD

This is part of the Medical Humanities Series on Op-Med, which showcases visual and literary art by our members. Do you have a poem or visual art piece you’d like to share with the community? Send it to us here.

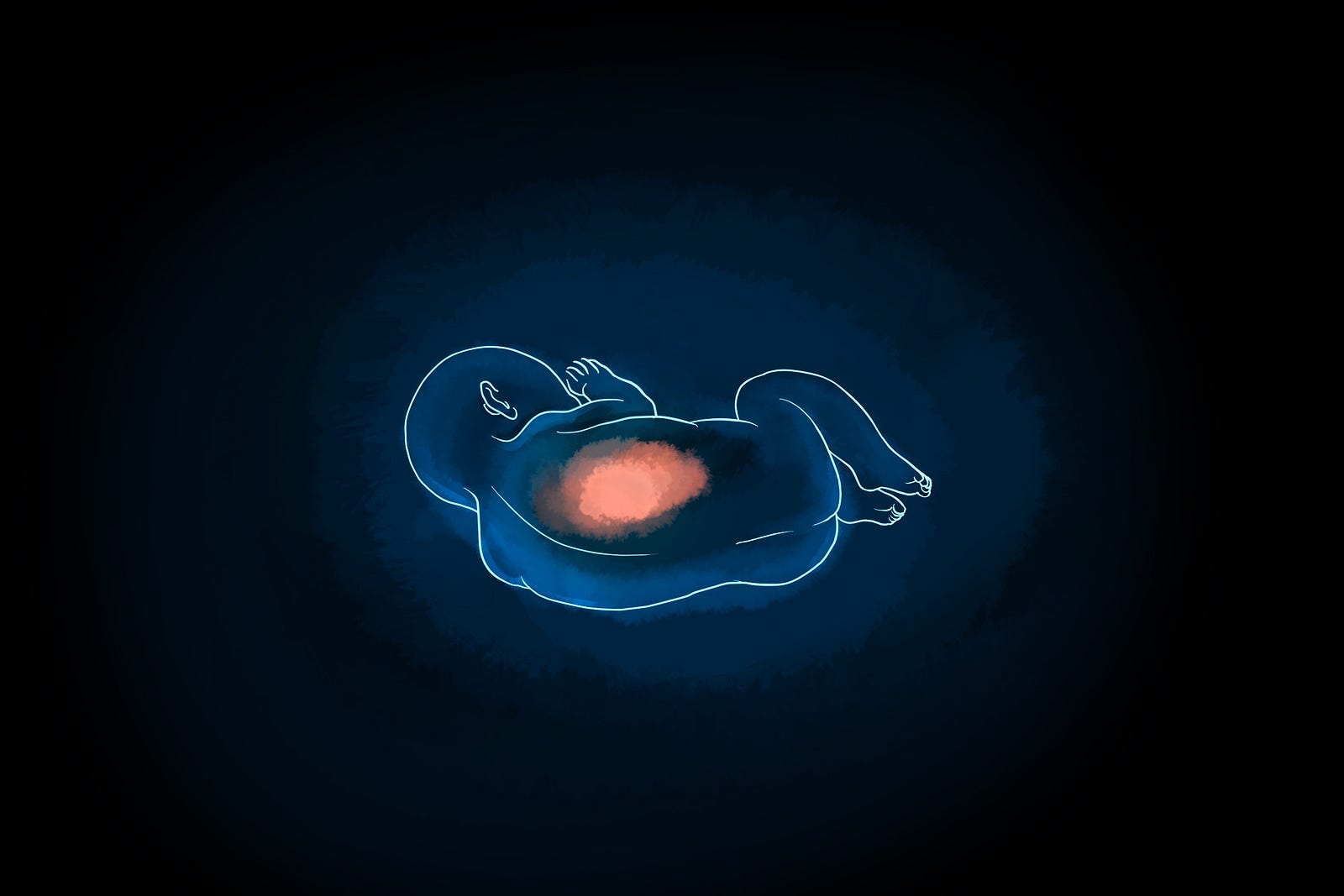

Apnea

They said it was normal

for premature infants to stop breathing

sometimes.

And though I'm sure they meant to reassure

it didn't feel like comfort, exactly.

If I thought about it from a place

outside the moment

I might believe

he would be all right.

But to see this small baby

not breathing. . .

I said I was afraid

we hadn't done enough

to make him want

to live

in this place of raw light,

plastic isolettes,

oxygen streaming

through the silicon tubing.

So I sit beside him

and make small human noises

against the whir and whine

of intensive care.

I clear my throat,

clack my tongue,

I make those "Oh my soul" sounds

you understand in conversation

without making out the words.

I wrap my palm

around his rump

so he can feel

the warmth of my hand

claiming him,

rocking him slowly

into the family.

from Taking the History, Nightshade Press, 1999.

What inspired this piece?

From the moment he was born I knew he was an old soul. As I stood by watching the flitterings of his anxious eyes I could see behind the dartings and jumpings that he was telling me he had forgiven it all in advance. Such a massive courage from such a small, thirty-second week premi, little larger than the palm of my hand! I wanted to celebrate his spirit, his anxious moments at the precipice of life, his urgent reachings for the attachment to love and understanding that would keep him in this world.

Why did you choose this form for this topic?

Poetry was my medium, my entry into the writing world. I had spent years slogging my way through bland poems reaching for something of importance. This opportunity and the connection it called forth in the form of this tiny, struggling infant seemed like the perfect moment for a poem. The poem urged itself on me. I didn’t have to think. The words just poured out.

How did you get into poetry? How does it relate to your medical practice?

I came to poetry out of an uncertain necessity. Stress, strife I thought I could handle, then my health failed. Instinctively I started writing poems. The poems were awful but therapeutic. Then I reasoned that if i was going to write poems it would be better if I knew what I was doing. Right? So I went back to college at night for a MA in English and Creative writing and attended the Squaw Valley Community of Writers umpteen times.

You run a workshop group at UCSF called Parnassus Poets. How did that get started?

I believed that it was important for a health sciences campus to offer something of humanistic value to nourish the starved (theoretical) “right hemisphere.” I kept the workshop open to folks on campus and abroad. It’s been going for over 30 years now and has produced many publications. More importantly, provided a place for creative minds to come together and thrive in a nourishing environment.

How have you balanced a career in medicine with the writing and publication of several books of poetry and fiction?

Once you get bit by the bug you’re done for. My antennae are constantly up, and I write whenever there is a moment wedged between things. I think my unconscious mind is working on the food I give it with the initial prompt so that when I return, the next stanza or paragraph drops easily to the page. It’s a schizophrenic lifestyle but stimulating, and I think that the two sides feed and nourish themselves on each other. The addiction means that when one publication is launched and there is a brief period of rest, then I find myself thinking about what the next project will be. The result is that I am grounded, more balanced, and, I must say, very content.

David Watts, MD is a gastroenterologist at UCSF. His most recent book of poems, Having and Keeping, was runner-up in the 2015 Brick Road Poetry Press contest and published as an Editor’s Choice in 2017. Previously, he’s published six books of poems, four anthologies, two collections of short stories and five novels. He is a classically trained musician, a physician on the list of Best American Doctors, and a retired television/radio host and NPR commentator. He has an active practice of medicine at UCSF and teaches poetry at the Fromm Institute. His lectures in medical schools and his essays deal mostly with the importance of humanistic values in the practice of medicine. He lives in Mill Valley, California with his family.