My mother’s was a quiet, peaceful dementia. I don’t recall her ever being agitated or angry. She just faded away. Her physical illness — polycythemia, a blood disease — she could comprehend, but her mental decline was more difficult for her to grasp. That is, she noticed it at first but later became oblivious.

My cousin Emily was the same way. She was frequently confused, with obvious memory loss but never agitated. Like my mother, her maternal aunt, she remained calm and placid. She knew she had lost her memory, but she accepted it. “Harry is my memory,” she once told me, referring to her husband of 50 years.

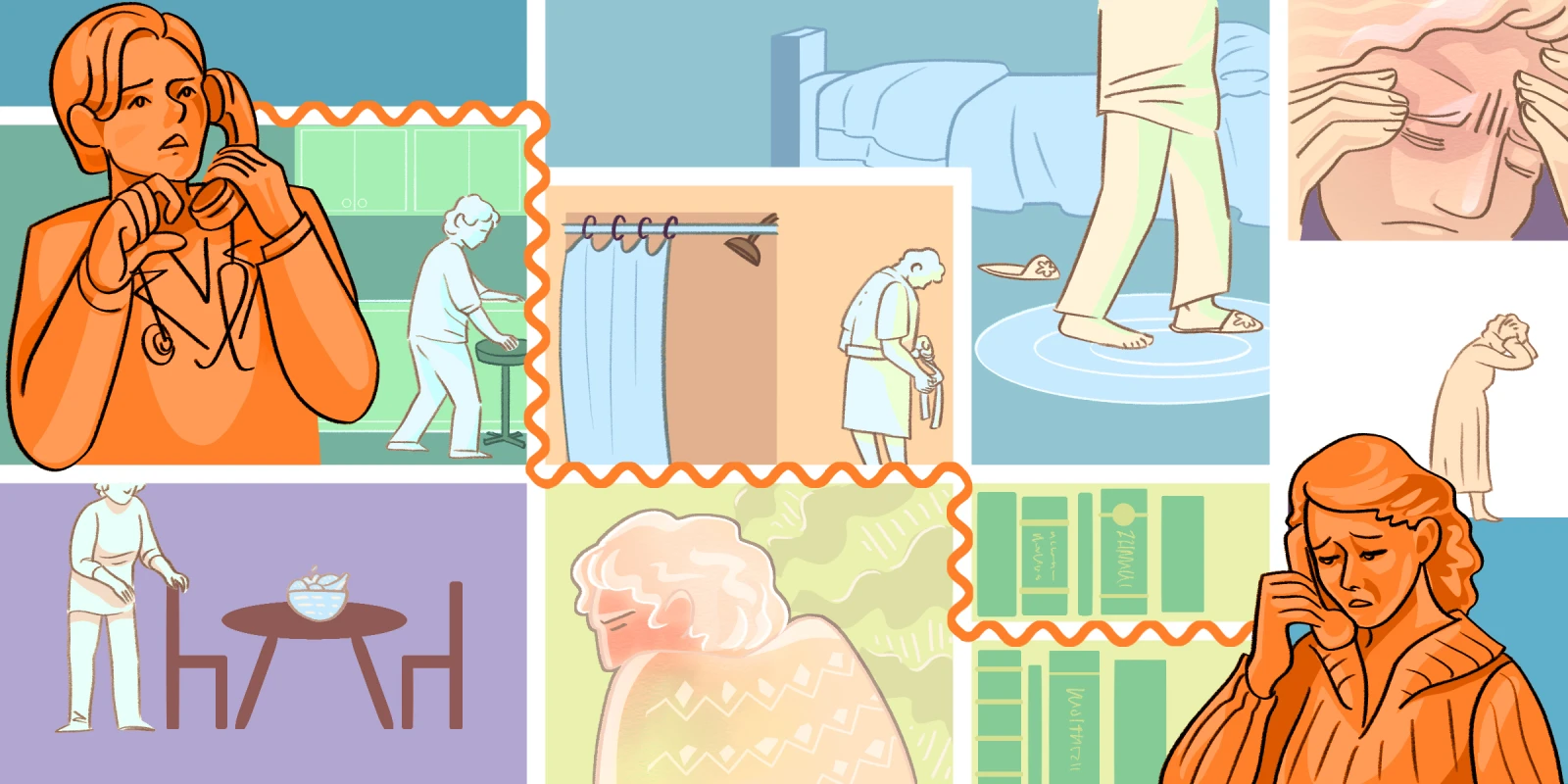

Dementia and Alzheimer’s are sneaky illnesses. We can do a lot of work to put them off, but if you’re not prepared, by the time you notice the warning signs, it may be too late. I have seen it firsthand with my mother and cousin, and now I see it with friends and patients, too.

When I first met Jill, her husband had already started developing symptoms of frontotemporal dementia, or Pick's disease, a condition distinct from and, fortunately, much less common than Alzheimer’s. It is marked by changes in personality and behavior. One day my friend’s husband would be perfectly normal, the next he would be someone else entirely, a total stranger — a doppelganger, she said. There is no known way to prevent, retard, or reverse frontotemporal dementia, only to manage the symptoms.

As for my patient Mary, she knows she has Alzheimer’s. Under my care, and with the able and dedicated assistance of her paid caregiver, she is fighting it tooth and nail. Unfortunately, the disease had a considerable head start. When Mary first came to me some 10 years ago, I didn’t yet know about some of the protocols that claim to reverse and prevent cognitive decline. There are numerous journal articles outlining nutrition, exercise, sleep, brain training, hormone replacement, and dietary supplements to try. Many participants report returning to normal function. Now that I do know about the protocols, I can advise her — better late than never; the battle is joined.

Recently, a former patient named Madeleine returned to me after a hiatus of several years. I have always loved Madeleine and was delighted that she called. Madeleine’s immediate concern was asthma — shortness of breath on climbing the stairs. Those problems responded promptly to immunotherapy. As we spoke, however, I noticed another problem — she was having trouble expressing herself, difficulty finding the right words. Indeed, Madeleine herself was concerned, remarking that it was starting to interfere with her social life. I ordered a panel of blood tests. When I got the results back, I didn’t know where to start — everything was off.

As a physician, I’m often torn between reviewing my patients’ labs in advance or looking at them while speaking to the patient, thereby enjoying their immediate input. Both have advantages. In this instance, I reviewed them first on my own. As I did, I made a list, suggesting a remedy for each test that was out of normal bounds, some prescriptive and some over-the-counter. At our appointment, I presented the list to Madeleine.

It was overwhelming, she complained. “Can’t we do one thing at a time?”

What was I thinking? Starting 20 new supplements or prescriptions at once is too much for anyone, let alone someone with cognitive challenges. Besides, often you don’t need to correct every wrong test. Fix one thing, and the others fall into place.

And that’s how we arrived at our new plan of weekly sessions — I call them my Wednesday afternoon happy time because I enjoy Madeline’s company so much. At each session I make one new suggestion. It’s been a month since she first called me, and already she’s noted an improvement. “I’m not saying ‘Um’ anymore!” she exclaimed. “I’m finding my words! I can talk again!” Hallelujah!

I had thought the cognitive decline wouldn’t improve as quickly as her asthma did, but it seems I was wrong. What I wasn’t able to do for my mother and my first cousin, I now hope to do for Madeleine, and every other patient who walks in my door.

Marjorie Ordene, MD is an integrative physician practicing in Brooklyn, NY. Her essays, short stories, and poetry have been published in various magazines and anthologies including The Sun, Tablet, Lilith, and Michigan Avenue Review. All names and identifying information have been modified to protect patient privacy.

Illustration by April Brust