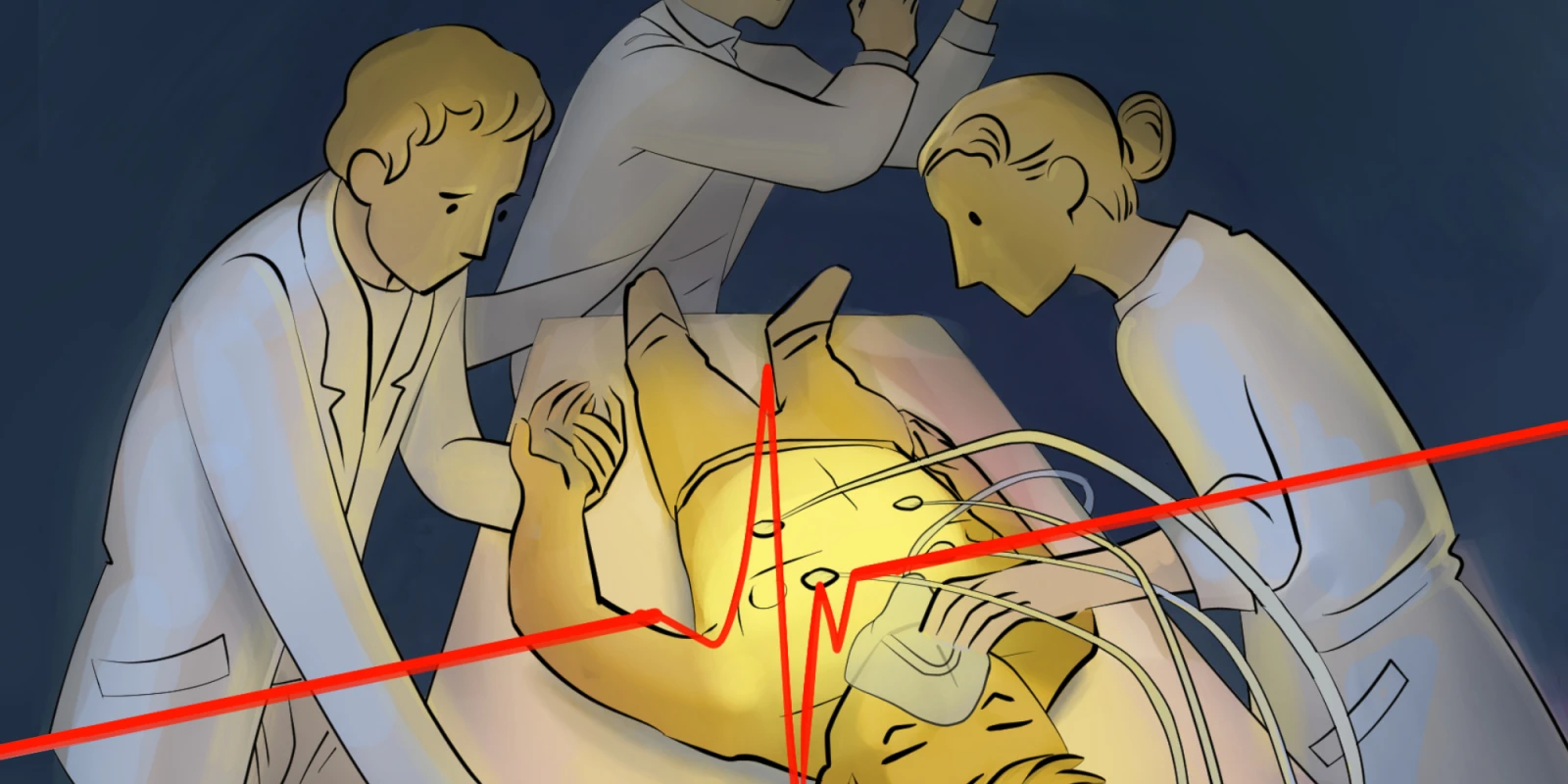

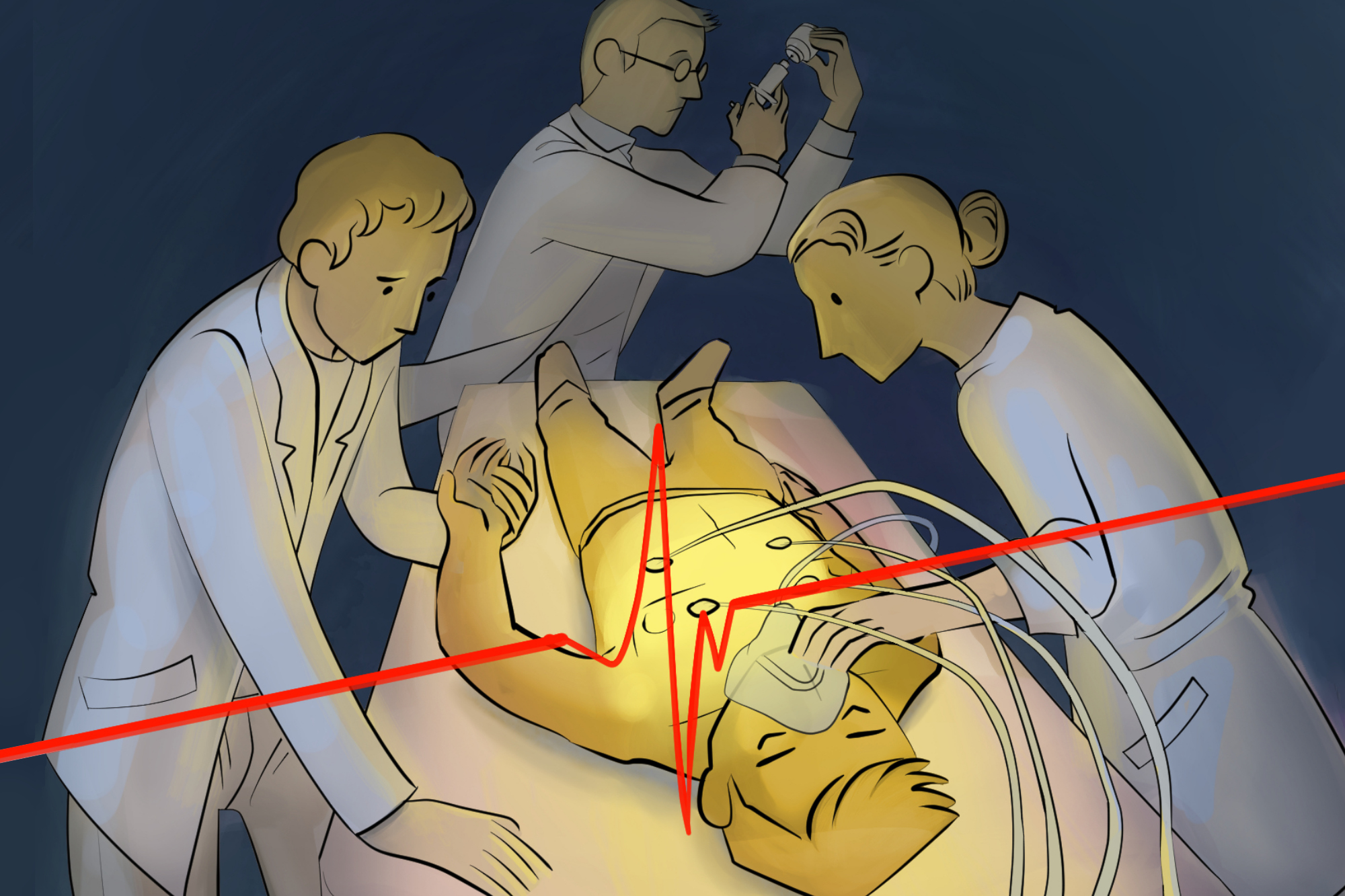

They were both dying.

Ms. Jones* was in her late 50s, and had been fighting cancer for the last half-decade, albeit unsuccessfully. This latest hospitalization was the result of an abdominal viscus with countless perforations, being inoperable and kept at bay for now with antibiotics.

Mr. Smith was just north of 80, and had spent the last handful of weeks at an outside hospital suffering from pancreatitis and all of its morbid sequelae. He had been intubated at least once during this time and was completely exhausted by the painful chore of “being kept alive,” in his own words.

Ostensibly, they were both dying.

There were no therapies left to offer Ms. Jones. She had completed chemotherapy and was not a candidate for surgical intervention. This perforation would be a terminal event. When it became clear that Ms. Jones was not going to rise above this insult, she elected to change her code status to “Do Not Resuscitate” with certainty.

Whenever this happens, there is, for lack of a better word, a certain “satisfaction” that we so often experience as clinicians. While patient’s autonomy trumps all — never needing to defend the election of a particular status — code status changes that seem so much more rational to us as clinicians make us feel like everyone is doing the right thing. After all, what is the utility in performing chest compressions and pushing epinephrine in someone who is slowly, yet actively dying? Barring the painful scenario of keeping a patient physiologically alive until a distant relative comes to say goodbye, these efforts are futile.

Ms. Jones was put on comfort care and was discharged very shortly thereafter to home hospice, allowing her to live out her final days at home, comfortably surrounded by family. No futile surgeries performed, no needless intubations, no daily venipunctures, no repeated trips to the CT scanner — just a comfortable bed and morphine PRN.

As we peer down the hallway to a room where Mr. Smith sits, we see quite the opposite story. Despite a month of hospitalization for this octogenarian, no progress had been made. He was still suffering, in both visceral and emotional pain. As the necessary antibiotics and TPN were leading to fluid overload, his pleura were filling with fluid. Our ICU team had a lengthy discussion with him about his goals of care during his lucidity. He explained that he would not want to spend a single day in rehab, let alone be intubated or receive chest compressions. He would rather die than have to go through any struggle; this past month in the hospital had been enough. As there was no path for him to get home other than through tremendous rehabilitation efforts, even with his mental faculties, the case seemed clear cut.

But his primary surgical team saw things differently. Hanging onto singular metrics like an improving white count or rising P/F ratio, they persuaded him to “give it 48 more hours” to see if he’d improve. Sure enough, during that time, he became delirious and had increased work of breathing. Meanwhile, his wife wanted “everything done to keep him alive,” in her words. As I entered the room to perform the intubation, he had a look in his eyes as if to say, “no, not again” to these futile attempts. As a mere resident on the team, I voiced my concerns in acting against his wishes, but ultimately my hands were tied. Mr. Smith was re-intubated. He died a few days later.

The moral conflict weighed on me much more than the ICU call schedule. I thought back to my doctoring classes in medical school — how autonomy was stressed above all else. His recent election to become full code along with his wife’s assertion that everything must be done certainly muddied the waters. In my mind, however, it was clear that Mr. Smith didn’t want any of it.

What are the take-home lessons from these similar yet different experiences?

First, it is essential to make sure all members of a care team are on the same page and deliver the same plan to the patient. While we wouldn’t change a code status ‘behind the back’ of a primary team, we were looking at Mr. Smith through a lens of futility, whereas his surgery team thought he could certainly get over this ‘bump in the road’ to improving his health. All of this was a moot point to us in a patient who would prefer to be dead than at a rehab facility. The chances of even making it to rehab were slim, and to the patient, even this wasn’t worth striving for.

Secondly, it is crucial not to let the minutiae cloud the big picture. As I have learned in my limited amount of time in the ICU, minutiae are all around us. It is this attention to detail that keeps patients alive and is necessary for their overall care. But hanging onto a lab value that looks better today than yesterday, in a patient who has been suffering is a recipe for delaying the inevitable.

Third, as an OR-based resident simply rotating through the ICU, I realized I am not a great prognosticator. Surely, ICU attendings who have been at it for decades can probably lay eyes on a patient and have a good sense of an endpoint. But people whose course looked declining and futile to me could bounce back over 36 hours and be healthy enough to leave the ICU. This makes it all the more difficult to decide which patients to perform relatively aggressive measures on.

Fourth, we must be mindful of the terminology and verbiage we use amongst ourselves and around families and patients. I found some of the jargon in the ICU off-putting. While colloquialisms can normalize these heavy and difficult experiences, to say that Mr. Smith’s wife wanting to go “full court press” never felt right to say even among our ears only. Explaining that the BAL sample came back with gram positive rods, or that the HIDA scan was equivocal means nothing to most lay people. Let them know that there a chance the patient has pneumonia, or that the gallbladder scan didn’t give us the information we were hoping for. What families really care about is whether or not the patient is getting better. Keep it simple.

Lastly, despite being clinicians, our families, friends, and even us will one day be patients in need of end-of-life care. When this day comes is completely unpredictable — that is why it’s essential to understand everyone’s wishes and advocate to make sure that the patient’s desires are the ones that we strive to act out.

These conversations are never comfortable to have amongst our own family members. However, a little bit of difficult discourse now in order to elucidate our loved one’s true wishes can prevent immeasurable pain and anguish when they cannot speak for themselves. Whether we are acting as family members or as doctors, it is selfish and immoral to put our own wishes and desires ahead of a patient’s needs.

Brian Radvansky, MD is an anesthesiology and critical care resident and blogs at the Med School Tutors’ blog. He is also a 2018–2019 Doximity Author.

Illustration by April Brust

*Disclaimer: All names and identifying information have been modified to protect patient privacy.