Op-Med ran the “First Stab” contest in November 2017. We are excited to announce this as the winning piece.

It was a beautiful day in Texas. At least that’s what I was told. I rarely left the hospital during the daylight and, devoid of windows, I usually created an image in my mind that bordered on fantasy. I was a pediatric surgery fellow. I had completed a busy surgery residency in Houston and had taken care of patients in busy trauma centers for the past 6 years. There was a parade today and the streets were full of families and couples and happy Texans celebrating an occasion I don’t recall or never knew.

A call came from trauma, a young girl, while enjoying the parade, had been stomped on by a frightened horse. I’ve always marveled at horses, and how comfortable parents are allowing their kids to ride and be around such a magnificent, powerful animal. Perhaps it’s because my son was only an infant when I cared for this girl, perhaps it’s that I lived on a farm when I was small and always recognized the independence of animals, their fear, their love, their frustration and potential for tantrums. Regardless, the child arrived in the trauma bay in near arrest. Blood started, chest tube inserted, abdomen massively distended, she coded, we got her back. She coded again, back. Coded again, back, and we ran like hell for the operating room. We packed her abdomen and her poor shattered liver and prayed to every god I could think of. For the time, it seemed we were winning. Unit after unit was pressed into her body, the operating room was warmed to steaming, minutes seemed seconds, seconds seemed hours. Time irrelevant as we struggled to keep her fragile body alive. We began removing packs timidly, terrified that the onslaught of uncontrollable hemorrhage would restart. As the pack was removed from behind the shattered, near particulate liver, I saw straight up the open vena cava and with that, she was gone. Air embolism, I assume, but no effort could bring her back to us, not even for a second. Fatigued, frustrated, devastated, I went to find the parents and bring them, as we commonly did, to the Operating room to see their daughter and say goodbye. This is the part of the job that no one wants. There is no way to do this nicely, gently or kindly. You will say words that no parent wants to hear. For that moment, and likely for many sleepless nights to come, you are their worst nightmare, the face that wakes them from restless sleep, the voice that echoes in their ears. I believe time with the deceased matters. They must know how hard she fought. They must see she tried, we tried. They need to say goodbye. Not that it matters in the end, I guess.

This family, like most, was devastated. They were shocked. They went to the operating room and I left them with the pastor and social worker and went to change.

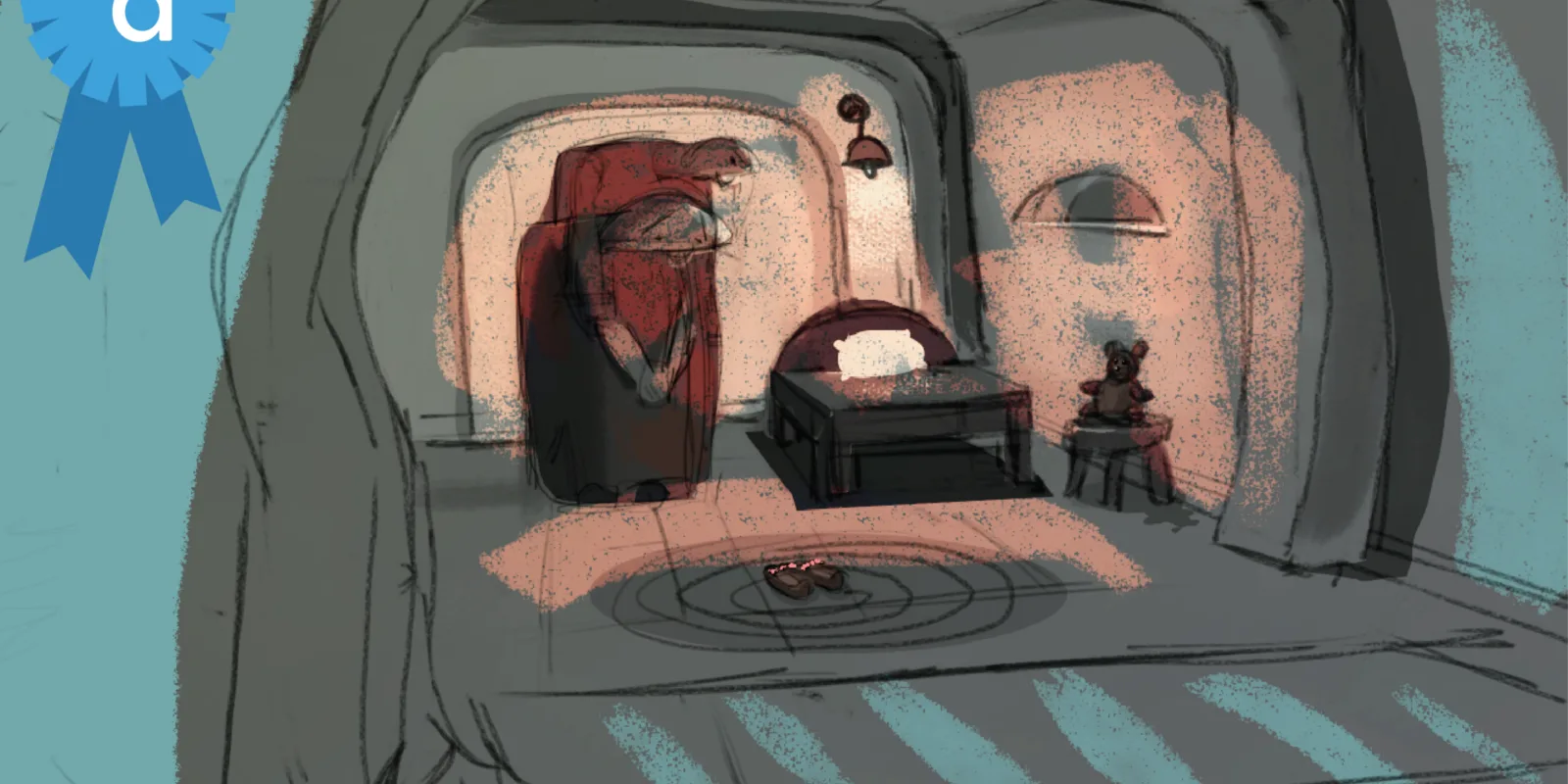

Work, of course, doesn’t stop when your patient dies, and I went on case after case from the early afternoon of the parade to the late night as the hospital darkens and quiets. The buzz of the preop suite quiets down and the lights go out, the recovery room has just one or 2 patients and the day staff has headed home to their families and activities. It was late, maybe 11 pm, when I passed by the dark family waiting room and headed to the surgeon’s lounge to see if any scrap of food remained. Fingers crossed for leftover Cheerios, I noticed someone in the waiting room and went closer to see a couple sitting there calmly in the dark. I opened the door and as they turned I realized it was the girl’s parents. Dumbfounded, I slowly walked toward them thinking maybe they misunderstood, perhaps the social worker didn’t tell them what to do next. Quietly, I asked them if I could help, were they waiting for anyone? The mom turned and said in an even voice, “We just couldn’t go home without her. How could we? To her room, to her toys, to her brother?” It wasn’t possible, after all, was it? And so, they had stayed, there in the dark. And there I stood, helpless, recognizing for the first time, as a doctor, as a surgeon, and as a mom, the tremendous void that is caused by the loss of a child. Never had I thought of going home to the child’s room, to her toys, to her place at the table. What it would be like to not kiss her and put her to bed that night. One child lost is one child too many. That night I learned the value of life, the meaning of love and what it means to say goodbye.

Dr. Holly Neville is a Pediatric Surgeon and Professor of Surgery at the University of Miami. She is a mom of 3, a safety and health nut, swimmer, runner and paddleboarder.