“I’m not feeling well.”

Little did I know that such a statement would radically change our lives. My partner and I would emerge on the other side with a completely overhauled approach to our health and with new revelations on how different the patient experience was from our previous notions.

But before all that, here I was leaving for work. My partner had mentioned that something was not feeling right. After having been together for several years, I knew his micro-expressions intimately: the way his eyes sparkled with joy and the slight brow furrow that appeared when he was in deep focus. And so when he mentioned he was not feeling well with a hint of panic, I knew this was not the extra beans type of unwell. It was an out of body experience as I quickly performed a cursory exam and dropped everything. We immediately headed to the nearest ED.

Over the course of the next 52 hours, as we were met with delay after delay, I began to take mental notes on the experience in order to keep myself sane. Below, I share the step-by-step process of taking my partner to the ER, as well as the takeaway lessons I’ve since incorporated into my own practice.

Arrival

When my partner and I arrived at the ED, we hoped we’d be seen right away. Unfortunately, we spent the next 24 hours in the hallway, surrounded by gurneys without barriers. The same words that I’d recited to patients many times before suddenly felt like a slight: “I’m sorry but the hospital is at capacity right now.” As a family member, I felt helpless. A wall of obstacles stood before us. The wait time. The redundancy. The lack of answers.

As a clinician, however, I felt like I had perspective. I was able to talk my partner through the medical jargon, the inefficiencies of the system. And I was able to empathize with the nurses who were tasked with fielding requests from both the medical team and the patient and their many family members. Two hands can only do so many things at a time. To help the nurses out, I found myself profusely apologizing every time I made a request. I was conscious of not acting like one of those family members.

Visitor Removal

At one point the ED became crowded and the security officer ushered us visitors out. My belongings and myself were directed unceremoniously to the lobby. During that time, I watched courtesy and care take on many forms among the front of house staff, from the apathetic to the empathetic. While I noted some staff would dismissively wave off family members whose question barely left their mouths, the staff with the extra bandwidth sourced additional seats so that families would be able to sit together and comfort one another. These were seemingly small gestures that provided great sanctuary on the island of isolation we inhabited.

I found solace at a small metal table sitting across from an older Spanish-speaking woman. I asked her in my best attempt at Spanish how long she had been there. Prophetically she told me it could have been minutes, it could have been hours.

Every so often as we heard rustles in the direction of the ED, the older woman and I exchanged glances followed by bemused head shakes. It was never for us. I was happy to share in her company as we both waited. She reminded me of my grandmother in her small stature, and sitting beside her was the closest to an emotional reprieve I had experienced so far.

At one point, I saw that the woman was eyeing the vending machine. There was no cafeteria. I reached into my bag and offered a granola bar, which she graciously accepted. She thanked me in Spanish and I nodded back, grateful for how she provided me with a sense of calm in a world both familiar and foreign to me.

Before this experience, I had never thought about the layout of a waiting room — the presence versus lack of food; the proximity versus distance of strangers. But afterward, I can’t unsee how big a difference it can make in family member/visitor comfort.

Reunion

Finally, after eight hours, my partner was allowed to have visitors again. His clinician must have asked him for the name of the person to look for and was told to find Helen. I waited with great anticipation next to a tall blonde woman also anxiously waiting. A clinician came through and immediately beelined to the blonde woman and directed her through the doors. It must be a busy time for updates, I thought to myself. Moments later they both returned — the clinician muttering that she had the wrong person and racing past me again as she scanned the room. I sensed she was looking for me. I introduced myself and she apologized as we walked toward my partner and she debriefed me on the day’s events.

Later on, I mused with my partner how it was surprising the name Helen didn’t conjure up a petite black-haired Chinese woman. It was an honest and innocent mistake, but it made me think about the number of inadvertent assumptions I’ve made in my practice. I once referred to a patient’s sons as “your sons” to her husband. He corrected me by saying they were HER children. Those first moments you develop rapport are crucial. I feel the best way to move forward from such events is to be transparent and apologize. This is what the clinician did, and reflecting back on the experience we greatly appreciated her care.

Day Two

I was not permitted to stay overnight the first evening, so I promised to return early in the morning. I’d heard from patients’ family members before that they were apprehensive about leaving because they feared they might miss out on an update. I now understood what that felt like. Home no longer felt like home without my partner. Sleep felt like a chore and an unnecessary obstacle in the search to find an answer. Usually an avid dreamer, I simply passed out that night from pure exhaustion.

When I woke up, I immediately texted my partner that I was coming with a fresh change of clothes, a warm blanket, and any creature comforts I could find. While discharge planning was not an option yet, it felt imperative that I incorporate elements of home into the hospital experience. This is something I now urge every patient of mine to do: bring something from home for your loved one to remind them of how much they are loved when you can’t be there.

Imaging

When my partner was first admitted, he expected to have a magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography test on the first day. However, this didn’t happen for almost 48 hours. Whenever we asked when imaging would occur, my partner and I would receive a vacant hand wave that indicated “soon,” but that really meant nothing.

After a full day of being NPO after imaging was promised and delayed, my partner began to feel frustrated. It was a physiological response. I could see the bags under his weary eyes. He was trying but finding it difficult to remain optimistic. He expressed that if the teams would be transparent it would make it easier to endure than if they kept promising and delaying.

I learned so much from this feedback. Often patients are not so much frustrated with what is not happening, but with the lack of explanation. They feel like they are being blindfolded in an already pitch dark room. Every moment that there is no update seems like an eternity for a patient, even though it may have only been minutes.

~~~

This experience was a challenging one, and one I hope I won’t have to repeat. And yet, in its own way, it was valuable. Beyond renewing my appreciation for the medical staff who kept us in the loop, even just to say they had no updates, it gave me a new perspective on patients’ family members.

For instance, by the second evening of my partner’s hospitalization, I could feel the toll on my body. The minimal food and sleep, endless phone calls, and emotional drain was a recipe for burnout. The self-care I preached to my patients suddenly became a full time job in itself. I could only imagine the amplified stress of balancing children, pets, and multiple jobs — often the situation for many patients. The experience softened my attitude toward the family members I’d encountered at their wits’ end. Sometimes labeled as difficult during “outbursts,” these families were now more understandable. In the future, they would receive a hall pass from me. I knew they were just doing the best they could.

As a result of this experience, I have tried my best to have my team continuously update my patients and apologize for delays. I also make a greater effort to advocate for my patients. I can say this experience has made me a more empathetic clinician.

There is a certain agony to watch someone you love struggle. Those moments you feel helpless and out of control are humbling. While on the same ride, as a medical clinician you are the captain driving the ship. But as a family member, you are a passenger. It is a privilege to experience the ride through the lens of both.

Have you ever been an ED patient or the family member of an ED patient? What did that experience teach you? Share in the comments!

Dr. Helen Chen is an integrated Geriatrics and Hospice and Palliative Care Fellow in New York City. She is a food lover and is always on the look out for the best bahn mi, falafel, and tacos (although is allergic to red onion and avocado!). Her instagram is @gouda_vs_evoo. Dr. Chen is a 2023–2024 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

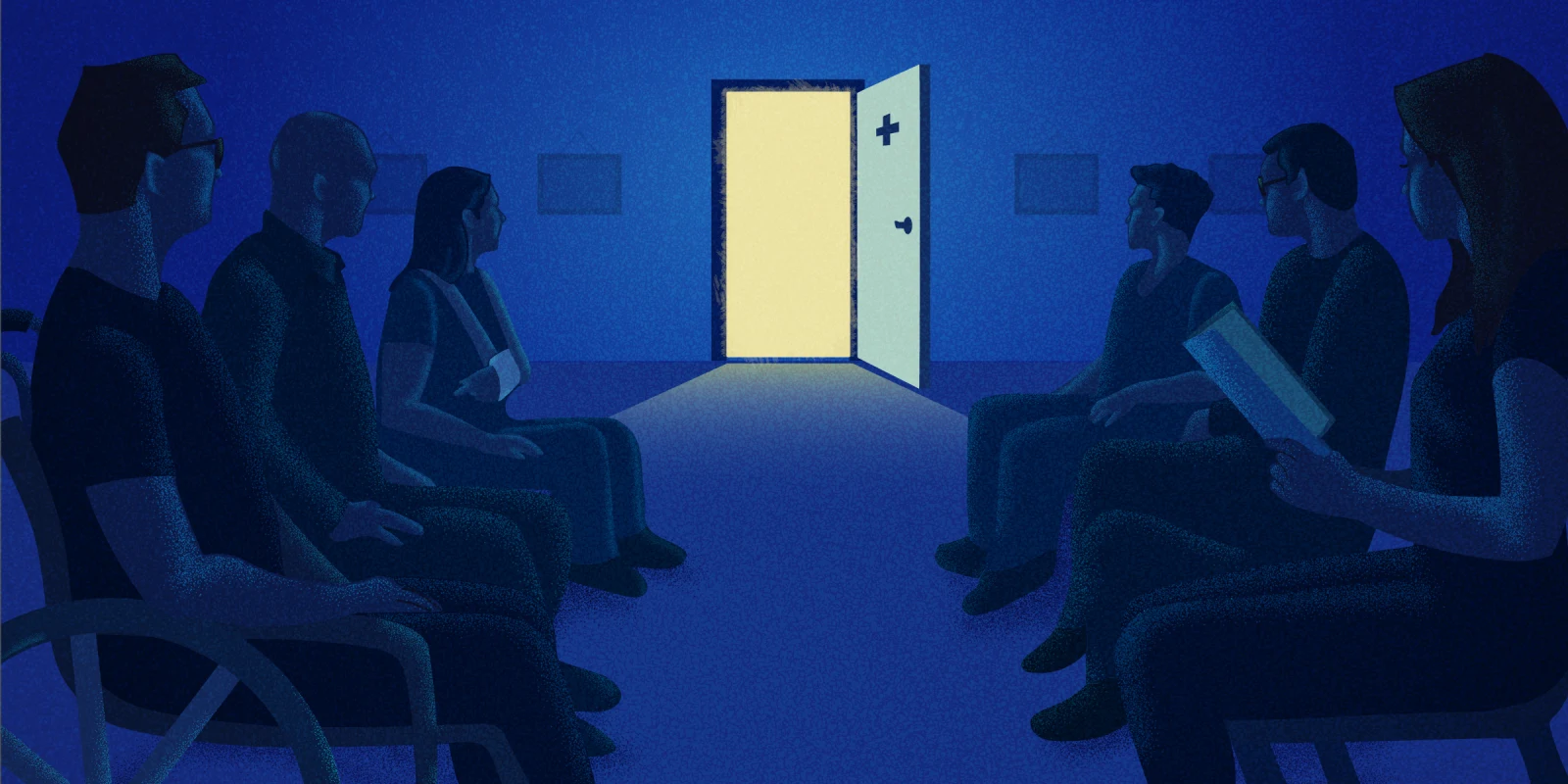

Illustration by Diana Connolly