My first exposure to periviability was during my third year of medical school. My preceptor organized a mock debate, where we explored the ethics of resuscitating an infant born at 23 weeks. Truthfully, perinatal viability had never been anything I had given much thought to. My time working in adult medicine had convinced me that between life and death there should be a space filled with ebbs and flows of life.

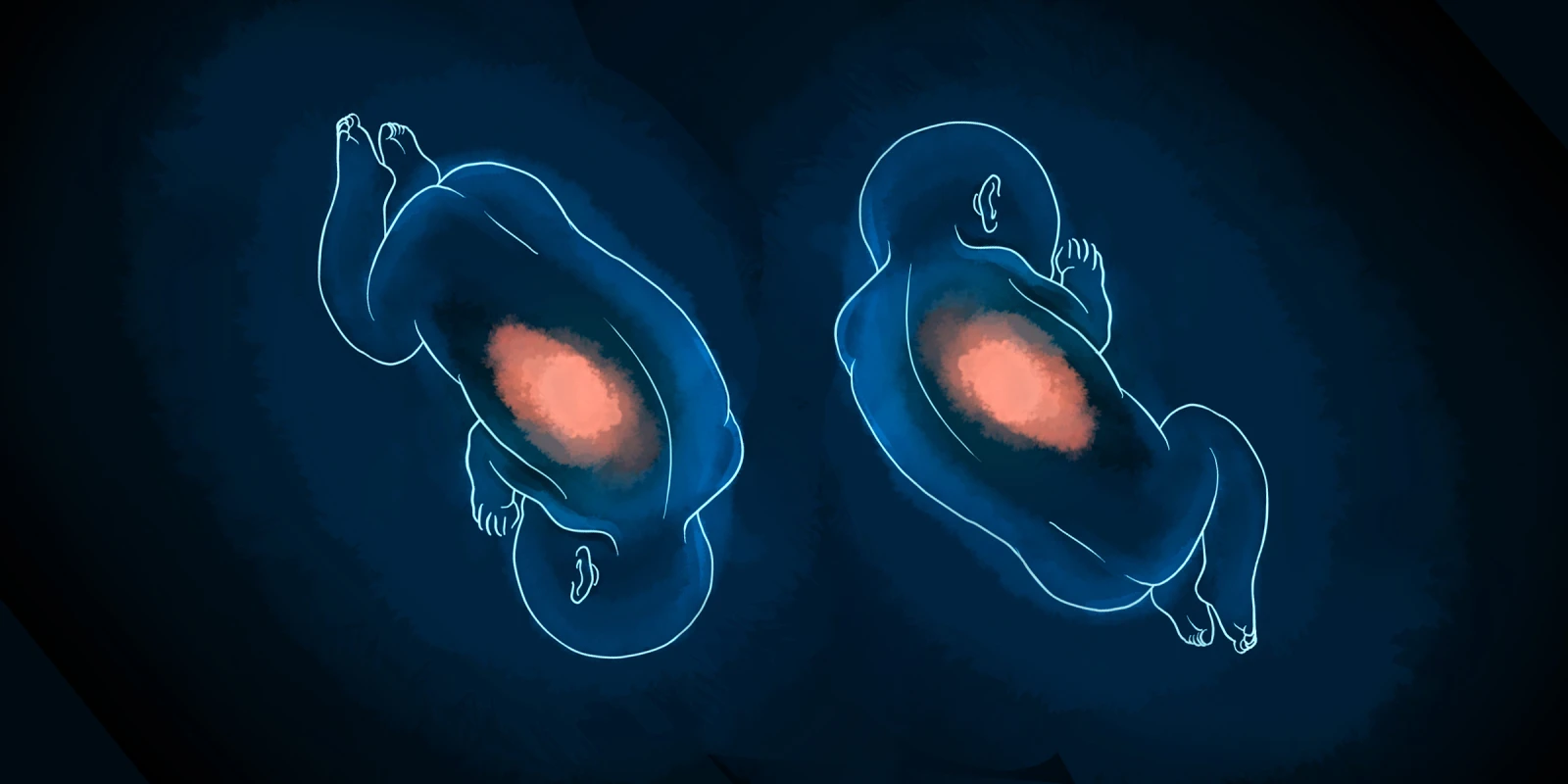

For infants born in the periviable period, life wasn’t about the “ebbs and flows.” It was about surviving until the next day. This concept was still abstract for me, and after my pediatric rotation ended, I assumed it would remain that way. Until one day on my high-risk ob/gyn rotation, when a patient with cervical insufficiency gave birth to twins. Amy and Jericho were born at 22 weeks and two days, and the parents requested life-saving measures.

Our NICU team rushed into action, providing resuscitation and oxygen immediately after birth. When they desatted, the team intubated them. When Jericho’s lungs collapsed, chest tubes were placed in hopes of breathing life into his tiny lungs. Despite heroic efforts, both babies died within 24 hours.

Amy and Jericho’s story isn’t atypical for infants born this young. Caring for infants born between 22 and 26 weeks requires significant hospital resources, and even with these, the mortality rate remains significantly high. In 2017, The New England Journal of Medicine published a multicenter study assessing outcomes for infants resuscitated after birth at 22 to 24 weeks. Infant survival ranged between 30% and 36%, and roughly half of these infants suffered long-term neurological sequelae. Practitioners caring for these infants know their efforts may be in vain and that saving a child may mean dooming that child to paralysis and intellectual disability.

Societal costs of periviable infant resuscitation are significant. One study published in Nature found that the average cost of six months of care for an infant born at 24 weeks is $603,778. Another study analyzed the cost-effectiveness of neonatal resuscitation at 22 weeks by determining quality-adjusted life years. When accounting for the mother's well-being, the study concluded that the best strategy was one of no attempted resuscitation. The disease burden carried by any infant that survived was too significant.

The importance of equitable access to health care is an important part of the undergraduate and graduate medical curriculum. To fight injustice, we must first acknowledge and learn about its existence. I think through this lens, it’s easy to understand the strategy of no resuscitation for premature infants — $600,000 is a significant sum of money to spend on one baby. If used to increase funding for preventative medicine, we could save significantly more lives.

Yet, this self-taught viewpoint of mine fell apart with Jericho and Amy. I couldn’t reconcile the viewpoint that their lives were possibly expendable. They were alive. They were given names. They were loved. Our interventions weren’t done in the name of futility; they were done in the name of hope. Hope that against all odds, Jericho and Amy had a future. A future of ebbs and flows, the same future I take for granted every day.

As neonatal care advances, we will continue to see better outcomes in the periviable period. However, there will always be a periviable period, and with it, there will always be controversy. At what gestational age should we offer resuscitative measures to parents? What truly constitutes futile care in premature infants? Is it fair to the infant to consider societal costs of periviable resuscitation? The decision to resuscitate or not resuscitate will never be one with a right or wrong answer. Rather, it will always be painted in varying shades of gray. Shades of gray that I am still learning to navigate.

Lachlan is a second-year medical student attending the USF Morsani College of Medicine. His interests include neurological research, medical humanities, and running. He is a 2022–2023 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

Illustration by April Brust