Dr. Mike Natter is a first-year internal medicine resident at New York University.

Diagnosed with type 1 diabetes at the age of nine, Dr. Mike Natter was always drawn to medicine. However, growing up as an artist who strayed away from math and science, he never believed he was fit for the field.

Following high school, Natter attended Skidmore University with the intention of pursuing a career in art. He constantly pushed away thoughts about medicine, in fear that he was unqualified for the profession.

It wasn’t until the end of his undergraduate career, when he began excelling in neuropsychology courses, that he gained the academic confidence to give medicine a chance. After a post-bacc program at Columbia, Natter matriculated into Sidney Kimmel Medical College. And, so began his trek towards becoming a physician.

Coming from a background of arts and humanities, Natter reveals that his transition into medical school was turbulent.

“It was petrifying for so many reasons. I had a pretty significant imposter syndrome. When I first went to medical school, I had this impression that I had to mask and hide a lot of my artistic side and cave into the more traditional way of learning medicine like my peers were doing, which, typically, was writing outlines, typing up notes, making notecards, reading, and highlighting. I did that out of fear that if I went about my normal way of drawing, making things more visual, I would fall behind or fail.

Well, it turns out I wasn’t doing so well in school this way. And, worse, I found that I was getting a little depressed, to be honest. Med school is such a high volume of information. There’s so much to memorize, and learn, and do. So, I spent a lot of time in the library — it became quite depressing and lonely.”

By attempting to mold himself into a traditional medical student, Natter abandoned his identity as an artist and sacrificed his mental health. He had lost sight of his creativity, and his grades were suffering for it.

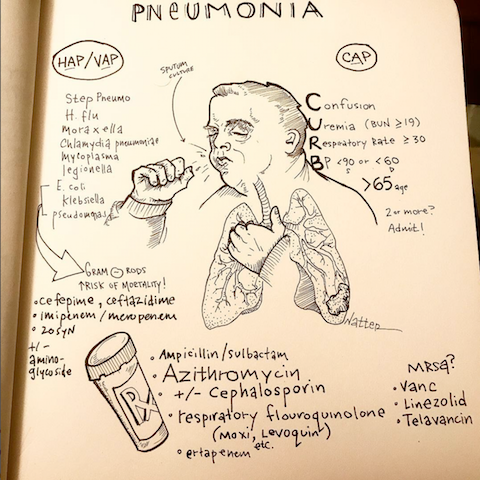

So, after some time, he decided to prioritize his well-being and return to his roots. He traded his notebook in for a sketchbook and began taking notes through drawings, diagrams, and flowcharts. Almost immediately, Natter noticed an improvement in his academic performance, meanwhile watching his happiness levels soar.

“If I didn’t start being true to myself and drawing more, I would not have been happy. And, the beauty of it, for me, was that I was able to combine, essentially, my hobby and passion into a very productive activity for medical school. It wasn’t like I had to trade out time for studying to go paint a picture. I was able to do both at once.

[…] It’s so necessary to do what you love — there’s a saying that ‘a warrior needs to unstring his bow,’ because if you keep it taught all the time, you won’t be able to absorb certain things. So, for me, drawing helps me absorb information. I think there’s something to be said about incorporating things that are not overtly academic into your academic ways.”

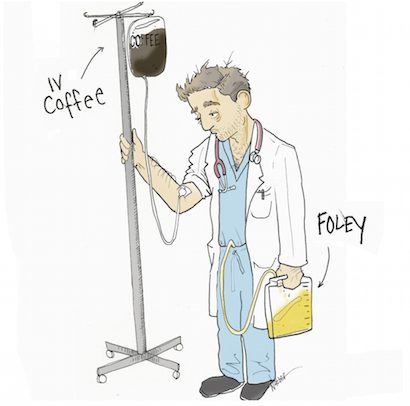

When Natter progressed into the later years of medical school and segued into patient wards, his artwork evolved to serve a new purpose: catharsis. As he started dealing with illness and death, first hand, he drew personal cartoons based on his encounters, experiences, and thoughts. These cartoons served as a coping method for Natter, offering him an emotional and creative outlet from the daily grind of medicine.

But, perhaps, what surprised him most, through this journey, were the reactions of his peers. While he had expected his classmates to mock him for his artistic tendencies, instead they encouraged him and even used his artwork as study material.

“Initially, especially when I first started med school, I would hide my doodles on the margins of my page and hope that no one would see them. And then, I would throw them out at the end of the day. But, when I found that they were helping me, I kept them and studied from them on my own. When they started to become more general and practical, I posted a few of them to my personal Facebook page.

And, it was shocking — when I started to post some of my notes and drawings on social media, my friends and peers and colleagues were also using my stuff to study from. That, for me, was a really rewarding part of it. Instead of this medical community scoffing at this art kid who’s doodling, they very much embraced it. It was very refreshing and made me much more comfortable in what I was doing.”

Natter was then inspired to publically share his drawings and cartoons on an Instagram account. Four years later, he has accumulated over 68,000 followers from around the world. He now partners with Portraits for Good in selling prints of his artwork to support the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation.

Now, as a first-year resident, Natter still manages to engage in art every day. Whether it’s drawing a diagram during a presentation, or sketching a cartoon in between rounds, he notes that art is imperative to his life in medicine. Without it, he wouldn’t survive.

“I draw every day. I have a little sketchbook that I keep in my white coat. Any time an attending gives us a lecture or a med student gives a presentation, or anytime I’m learning something, I pull it out and take notes in visual form. So, that’s more of my personal stuff.

There are also times, where I’ll be in a rotation that affords me a little bit more time. Then, I’ll take the time to really sit down and draw. Most of my illustrations these days are about confronting what I see in a normal day — things that are really tough to deal with — a lot of death and dying and end of life things. That kind of stuff really sits with me. For me, it’s really cathartic and necessary to illustrate and talk about it.

I love medicine. I love helping people and using my knowledge to fix things and think things through, but it’s also extremely exhausting and taxing and debilitating — it’s really hard. Art allows me this balance by talking about it and expressing myself in that language.”