“I will keep them from harm and injustice.” (Hippocratic Oath: Classical Version)

Residency had been over half a week. I had been on my first attending job half a day. My morning terror had waxed and waned; something else replaced it when a staff nurse asked if I had enjoyed the book I had read at lunch, the one I stared at sitting on a park bench across the street from the hospital, taking deep breaths while the words swam on the page.

My two o’clock patient in my new radiation oncology clinic was 54, a twenty-year breast cancer survivor, a producer of pristine mammograms as regular as a clock, every 366 days on the dot. Her waiting room checklist of interval tests and symptoms showed a long column of “No. No. No.” When I saw her in the exam room, I launched into a review of systems, asking her every conceivable symptom she might have had since her last visit a year before with my predecessor. The patient stared at me, bewildered at first and then amused, while I marched through what turned out to be a First-Day-of-Practice-Yesterday-I-Was-A-Resident-and-Today-I’m-In-Charge Anal Compulsive Review of Systems.

After five or six organ systems she simply began laughing, her hands held up in front of her face, “No, doctor, no. No, I haven’t had nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, bloody stools, change in stool size, shape or number; no, I haven’t had any bloating, weight gain, abdominal pain, weight loss, constipation, obstipation, no, I have no new lumps, no new bumps, no belly button lumpiness, no, no, no, nothing!” Also laughing I continued on, helpless to do anything but grind through the list until I got to the finish.

“And no headaches, or floaters, or difficulty with coordination?” I asked. “No, no, no.” “No weakness, or fainting spells or difficulty with gait?” “No, no, no.” “Any tingling or electricity or numbness at all?” And there was just the slightest missed beat when she said, “No, no, no, no, only when I wipe.”

Only when I wipe.

It took a long while for me to move my eyes from the patient to those of the veteran nurse standing at her back. It took me a long period — maybe forever — to review everything I knew about the biology of breast cancer, and how the risk of metastatic disease is always there, and how you’re never really out of the woods, and how breast cancer often has a predilection to spread to bones, and bigger bones at that, and then I started reviewing in my head the nerve tracks from the sacrum and how they influenced sensation in the perineum and finally after a long moment, a very long moment, I raised my eyes and looked again at the nurse and saw the small nod she made with her eyelashes, her affirmation of what we had just heard, and what we both knew it meant.

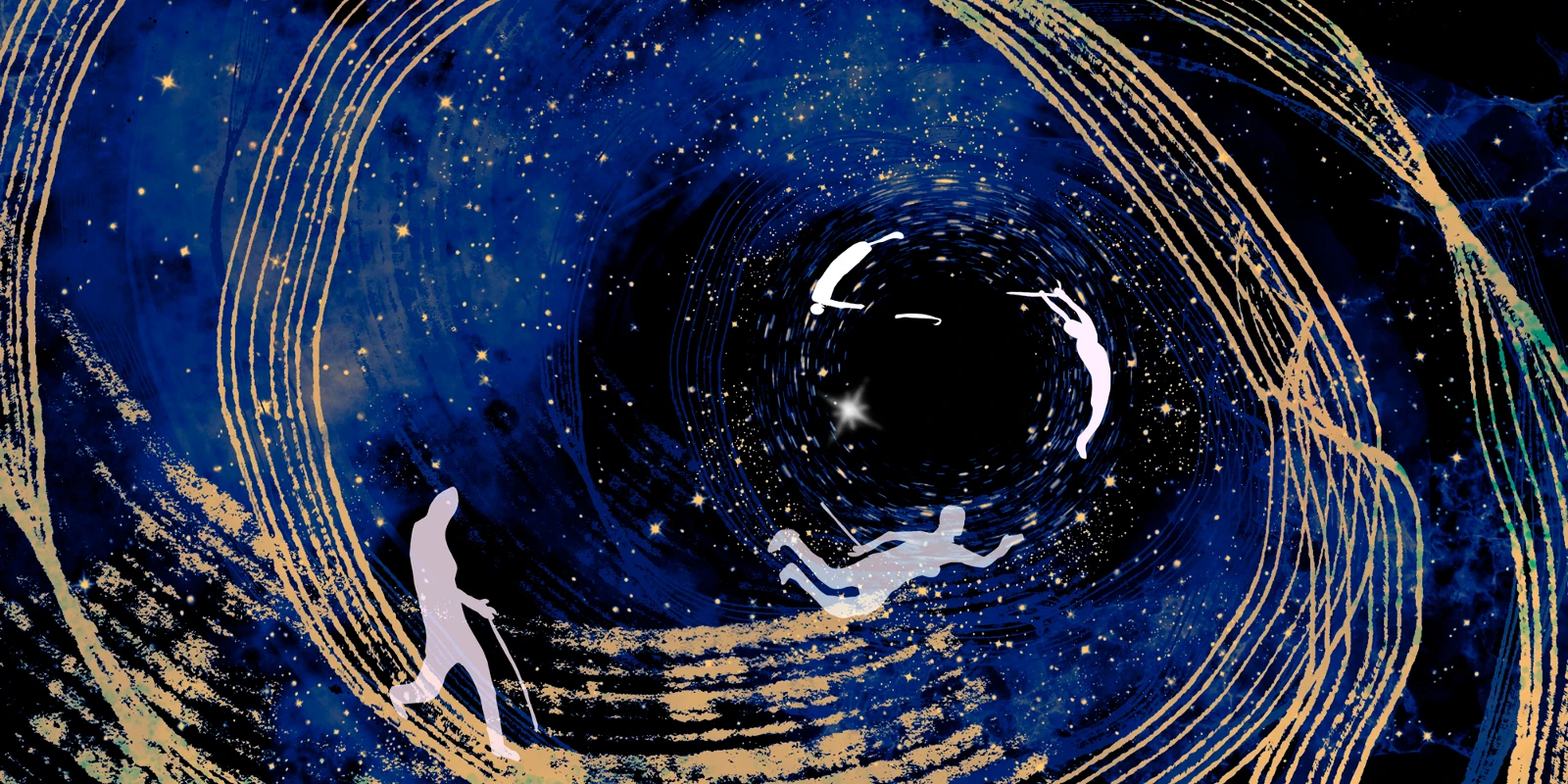

It took a relatively short time to get the scans that showed the lytic lesion in her sacrum, the only metastasis in her body but the first of many; within months her bones looked like stardust. It took less time still to arrange the radiation and get the chemo consult.

She was dead and gone in 18 months, a horrifying blow to us all. She walked the day she died.

Robin Schoenthaler is a radiation oncologist at the Massachusetts General Hospital. She has been treating people with cancer for 26 years and writing about the experience for much of her career. She has been widely published in the Boston Globe, New England Journal of Medicine, Reader’s Digest, Pulse Magazine and has a website at www.DrRobin.org.