Flying can be physically and emotionally challenging, particularly for the elderly and those with preexisting medical issues. Cramped conditions can possibly lead to blood clotting, cabin pressure fluctuations to ear issues, turbulence to nausea and vomiting, the dry environment to dry skin and mucous membranes and possibly dehydration, and the relatively low cabin oxygen pressures to hypoxemia and cardiopulmonary issues.

MedAire reports that the most common in-flight medical events are GI/nausea (31%), neurological, e.g., fainting or seizures (26%), respiratory (7%), cardiovascular (5%), and dermatological (5%).

I have been on numerous flights where the following PA announcement was made: “If there are any medical personnel on this flight, we require your assistance.” This announcement always quickens my pulse because of my concern for needing to address a possible issue that I may not have the greatest familiarity with, being a urologist with focus on the urinary and genital tracts. On a recent flight, a neurosurgeon, a radiation oncologist, and I together attended an anxious middle-aged man having abdominal pain who happened to be scheduled for gallbladder surgery three days later. We deemed him to be not acutely ill and informed the flight attendant, who relayed the message to the captain that neither flight diversion nor calling for emergency services upon landing was necessary. Fortunately, this was an easy one, unlike many other potential situations that can occur at 39,000 feet.

A few months prior, a similar situation occurred on another flight, and I deferred to an EM physician. Sometime after the EM doctor attended to this ill passenger, there was another PA announcement by the flight attendant seeking Gatorade or any form of electrolytes that passengers might have in their possession that could be used for this patient.

I have been disappointed with the disorganized, chaotic, and haphazard in-flight medical assistance state of affairs. As a physician who has been called upon to assist passengers, I have been clueless as to the contents of the airplane’s emergency medical kit. Does it have an EpiPen? A tracheotomy kit? A urethral catheter? Are automatic external defibrillators available on all commercial flights? Is there the wherewithal to start an intravenous line and hydrate a patient and administer intravenous medications? A pulse oximeter? Intubation equipment? What meds are in the kit?

It occurred to me that this process could easily be improved, of benefit to the passenger in need of medical care, advantageous to the airline and crew, and helpful to the physician who would be optimally prepared.

I propose that when a physician books a flight, they should have the option of identifying themself as a physician and volunteering their medical services. Before departure, the flight attendants and crew would have knowledge of the presence of the physician(s), their seat location(s), and the fact that they could be called upon for passenger aid. This would be efficient and would eliminate the need for a PA announcement that a medical emergency is in progress, which can be distressing to other passengers.

I suggest that all emergency medical kits on commercial flights be standardized. Furthermore, there should be adequate medical supplies available in the kit so that the crew does not have to seek supplies from passengers! Importantly, the physician(s) would be apprised of the precise contents of the emergency medical kit in advance of departure and able to familiarize themselves with its contents and prepare in advance for a variety of contingencies.

Mike Arnot, the founder of Boarding Pass NYC, a New York-based travel brand, has written some insightful information about the online emergency medical process that is summarized in the paragraphs that follow. I was not privy to any of this info prior to researching it.

Apparently, the Federal Aviation Administration requires an automatic external defibrillator on any flight that has 30 passengers or more. They also require an emergency medical kit that must include the following items: blood pressure cuff; non-narcotic pain meds and aspirin; antihistamine; atropine; bronchodilator inhalant; epinephrine for cardiac resuscitation; lidocaine; IV administration supplies; Ambu bag; CPR mask. Often airlines will supplement the basic kit with the following: anti-nausea medication; EpiPen; antacids; furosemide for water retention; glucagon for low blood sugar; naloxone nasal spray for opioid overdoses.

MedAire, founded in 1985 by a flight nurse, is an aeromedical organization located in an ER in Phoenix, Arizona. MedAire physicians practice emergency medicine and rotate fielding in-flight calls (approximately 100 per day). When an in-flight medical emergency occurs, the crew is supposed to contact MedAire while also paging to see if there are any medical professionals on board. According to MedAire, aeromedical experts on the ground collaborate with the onboard medical volunteers to assist with the administration of any recommended treatments. However, in all the in-flight medical emergencies I have been involved with, I had never heard of nor had any contact with this organization.

As pilots desire protocol and routine, so protocol and routine should likewise be applied to the process of in-flight medical emergencies. It is my pleasure and privilege to be able to help passengers in need, but the process needs to be optimized. I submitted my proposals in writing to the Federal Aviation Administration but have not received any reply as of yet.

Have you ever had to assist with an in-flight medical emergency? Share in the comments.

Dr. Siegel is a urologist who has been in practice in the New York metro area for 34 years. He writes a weekly health and wellness blog (www.healthdoc13.com) and is the author of several health-related books.

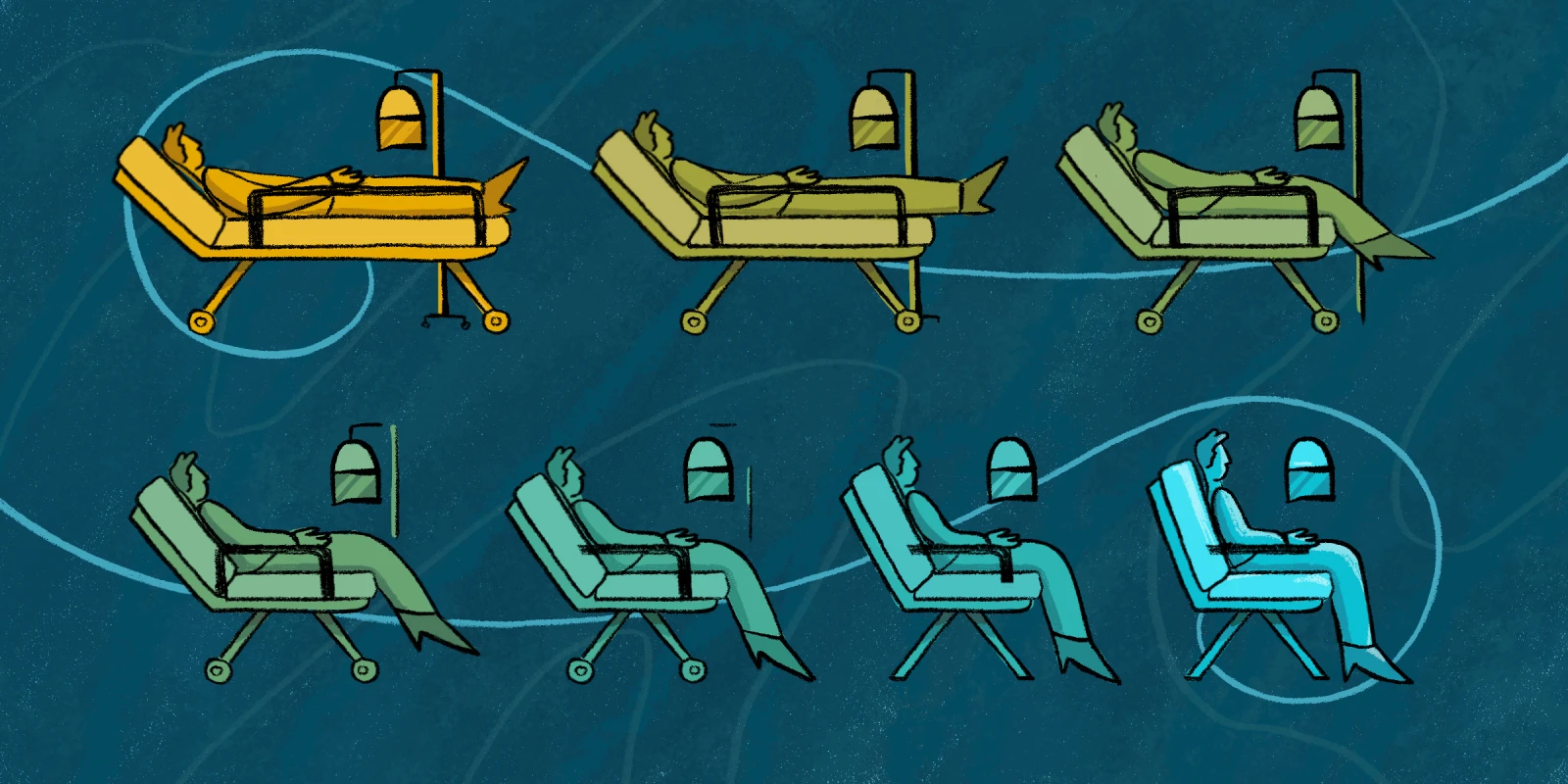

Illustration by Diana Connolly