Fifty years ago, during my third year of general surgical residency, I was assigned an elderly lady in the ICU who was in a coma. She soon developed a fever and I, intent on displaying my competency, pursued every conceivable test, including a spinal puncture. The fever responded to antibiotics, although her overall status remained unchanged. My superiors seem pleased with my efforts, but the ICU nurses did not seem to share the sentiment. The fever recurred several times and on each occasion the patient responded. By my measure, my efforts were successful. But apparently not by the standard of the head ICU nurse, who seemed particularly unimpressed.

After one of my infrequent days off, I returned to find that the familiar spot that my patient occupied was now empty of bed and patient. This was disconcerting, as she was a constant in my world that was otherwise a changing cavalcade of faces and problems.

When I questioned the head nurse about the patient, she replied that one of her nurses had “tripped over” the respirator cord, resulting in the patient's death. I assumed my patient had had some sort of event in my absence, and had been intubated and placed on a respirator. Following my hesitant laughter, supposing this comment to be morbid humor, I once again queried as to what had actually occurred. The head nurse emphatically repeated her answer. But what wasn't said was clearly expressed in her disapproving eyes: “You residents know so much about keeping your patients alive, but you don't know when to let them go.”

After searching my conscience, I found myself not without an element of guilt, seeing my actions through the nurse's seasoned eyes. This lesson would not be forgotten, and the new insight would soon be put to the test.

It was late afternoon nearing the Fourth of July weekend when I received a STAT page from the ER. They informed me of a young patient who had been gravely injured as a result of an explosion while building homemade fireworks.

On entering the ER, a quick survey revealed an unconscious teenager with third degree burns, along with two or three large areas of exposed muscle of his chest and abdomen. I heard the chief resident, a Vietnam War veteran, comment to another one of our surgeons, also a veteran, “He looks like one of our Claymore mine patients in 'Nam.” It seemed that every part of this teenager's body was damaged — but the injuries that left the greatest impression were his obliterated eardrums and collapsed eyes.

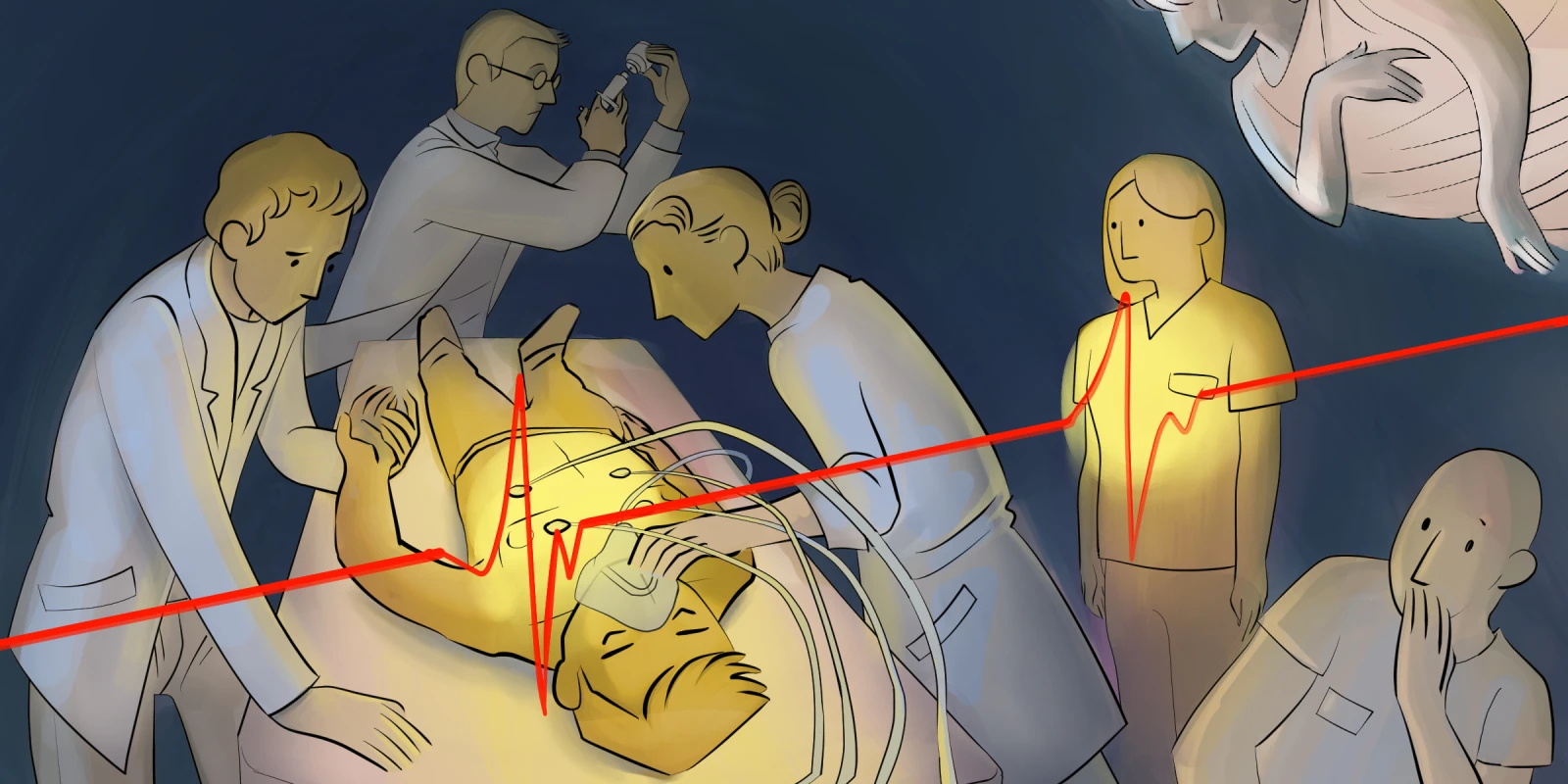

The patient's most life-threatening problems were his internal injuries, which would require emergency exploratory surgery. He was immediately taken to the OR where we explored his abdomen and then his chest. The staff surgeon performed an open massage of the heart, the first time I had witnessed this extreme measure. After repairing as much as possible, we eventually closed.

The patient was transferred to the ICU and the rest of the surgical team drifted away for the weekend. I was unable to leave the ICU at any time because his deteriorating status required my constant attention. While on call, the expectation was that we would work all night without sleep, which was not only assumed but a point of pride in our surgical culture. But as the evening became the early morning hours and I was required to issue an unending stream of life-sustaining orders, I sensed an exhaustion not of the physical but of the emotional kind.

This is the only explanation I can summon to justify my next action. I noted that the ICU bed next to the patient’s was empty and separated by only a curtain. I pulled back the curtain and lay down on the empty bed and closed my eyes. I now had only one medication left in my arsenal. As the ICU nurse called out the patient's blood pressure readings, which were ever lower, I would respond with an order to increase the medication. Eventually, I heard the characteristic sound of a flatline EKG. As the patient was young and previously in perfect health, it would be expected that everything possible would be done to sustain life.

The next course of action would be to call a code and start the resuscitation. In those days before there was a protocol for DNR orders, what awaited was as much an ethical decision as a medical one and it had been made; I would not subject this tattered husk of a human being to that final indignity.

I could sense there were now three ICU nurses who were hovering around the patient, awaiting my order. Arising to the sitting position to meet their gaze, I simply stated, "I'll call the family now,” and instead of questioning eyes or pleas to start the code, I was met with relieved expressions of agreement.

While in training, physicians assume that advice will come from revered professors and valued mentors, but guidance can come from myriad sources in our path though this journey called medicine. And so, a nonverbal life lesson learned from the glare of a hardened ICU nurse steered my decision-making process in these defining moments of a young surgeon’s education. And perhaps in retrospect, I should have recognized the proper course of action from my time in Sunday school where I first heard the admonition from Ecclesiastes that there is, indeed, a time to die.

Have you ever learned crucial lessons from clinicians with credentials different from your own? Share your experiences in the comments below.

Dr. Anthony J. Pizzo, MD practiced plastic surgery for 35 years and is currently retired and living in Tampa, Florida.

Illustration by April Brust