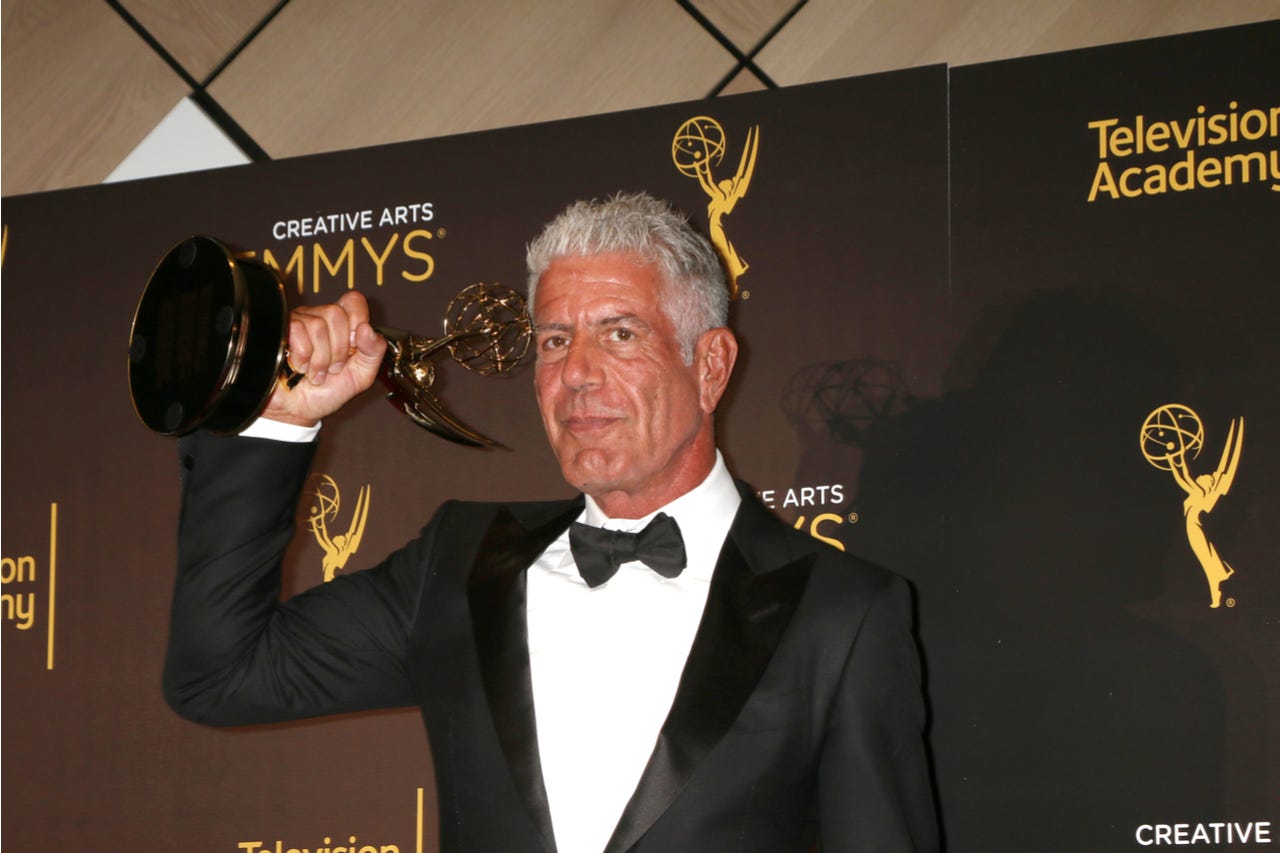

I heard about Mr. Bourdain’s passing on talk radio on the morning of June 8, 2018 at 6AM CST. I was driving from Rockford, Illinois to a Chicago suburb to observe a radical procedure an anesthesiologist has been using to treat PTSD in my never ending quest for newer and better ways to offer relief for my patients (more on that in a moment).

The manner of death was not initially mentioned by the talk show host, and my first (somewhat morbid, I admit) thought was, “No more reservations…” As a fan, I was sad to hear the news, but there was still room in my heart for a little levity. Tony seemed the kind of person that probably would have enjoyed my quip at his expense. A few minutes later the full news report came in that he had taken his own life, the second time a celebrity had done so within the week (and just 1 in 121 that will have occurred in the United States by day’s end). My sadness shifted into melancholy. Suddenly I was struck by the finality of what I had originally been musing as an irreverent epitaph.

It has been said that suicide is a permanent solution to a temporary problem. As a psychiatrist I often feel obligated to say something profound at times like these. But I have nothing.

I have experienced this type of loss up close often enough to know that we are always left with more questions and with little, if any, answers. Try as we do, we cannot predict who and when. As suicide rates in the U.S. have risen by almost 30% in the last 15 years, all we have really been able to do is be present and continue to offer hope.

A few years ago, a young man I had treated since he was in high school took his life. Despite his severe OCD and depression, and surviving the suicide of his mother when he was growing up, he was able to complete graduate school, get married, and find fulfilling employment. Although he moved to another state, he continued to see me for a few years, until he chose to seek treatment locally. Several months after our last session, he called me on a late Friday afternoon in tears. His symptoms had become unmanageable again, as they did from time to time, and he had consulted with a psychiatrist in his area. After reviewing his history and his records, the psychiatrist reportedly told him he was “too sick” and that she could not help him. I inquired about thoughts of suicide (which he denied), made some suggestions to adjust his medications, and asked him to come see me first thing Monday morning. He was gone by Saturday evening. His wife found him. His hope had gone and he along with it.

Although psychiatry as a specialty continues to evolve at a rapid pace, the advances in medication management seem to have slowed somewhat over the past decade. Even as newer antidepressants and other psychotropics are released, what we continue to offer are little more than slightly different ways of slicing the same pie filled with serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine.

But other advances in the field show promise. The rising use of pharmacogenomics, recently tossed onto the landscape as we navigate the often dangerous terrain of writing prescriptions, has been a game changer for many practitioners. Brain stimulation techniques such as transcranial magnetic stimulation offer relief to the treatment resistant or to those who cannot tolerate antidepressant medications. A form of ketamine also for treatment resistant depression is currently in trials for FDA approval. Of course, it is important to proceed with caution as we choose whether or not or how to incorporate these new methods into our practices. But I believe that inaction due to stagnation is an unacceptable position to maintain as well because it stifles hope.

Returning to the procedure I witnessed on the morning of Anthony Bourdain’s death. What I witnessed then was, dare I say, nothing seemingly short of miraculous. “Too good to be true,” said my colleague who observed the procedure with me. Perhaps, but we saw suffering mitigated almost immediately. We were energized by the potential applications for this treatment despite our skepticism.

And so ended another week of battling the disease. In the darkness a glimmer of light — of hope. We have to keep looking for that light. Without it, there are no more reservations indeed.

If you need help right now, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1–800–273-TALK (8255) or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741–741.