“Is it alright if I die now?” Mr. Walker murmured to his wife of more than 50 years. During these final moments, his voice was feeble but his determination to remain lucid against the sedating effects of his pharmaceutical cocktail and waxing delirium was overwhelming. His weak and slurring speech went unnoticed by his wife, Mrs. Walker, who was hard of hearing. Their daughter, standing to the side of the room, repeated tearfully, “Mom, Dad is wondering if he can go now.” Mrs. Walker’s gaze was unwavering, her hands intertwined with his. Perhaps if she clasped tightly enough, he wouldn’t have to go. Her eyes welled up with tears, and reluctantly, but not wholly devoid of relief, she acquiesced.

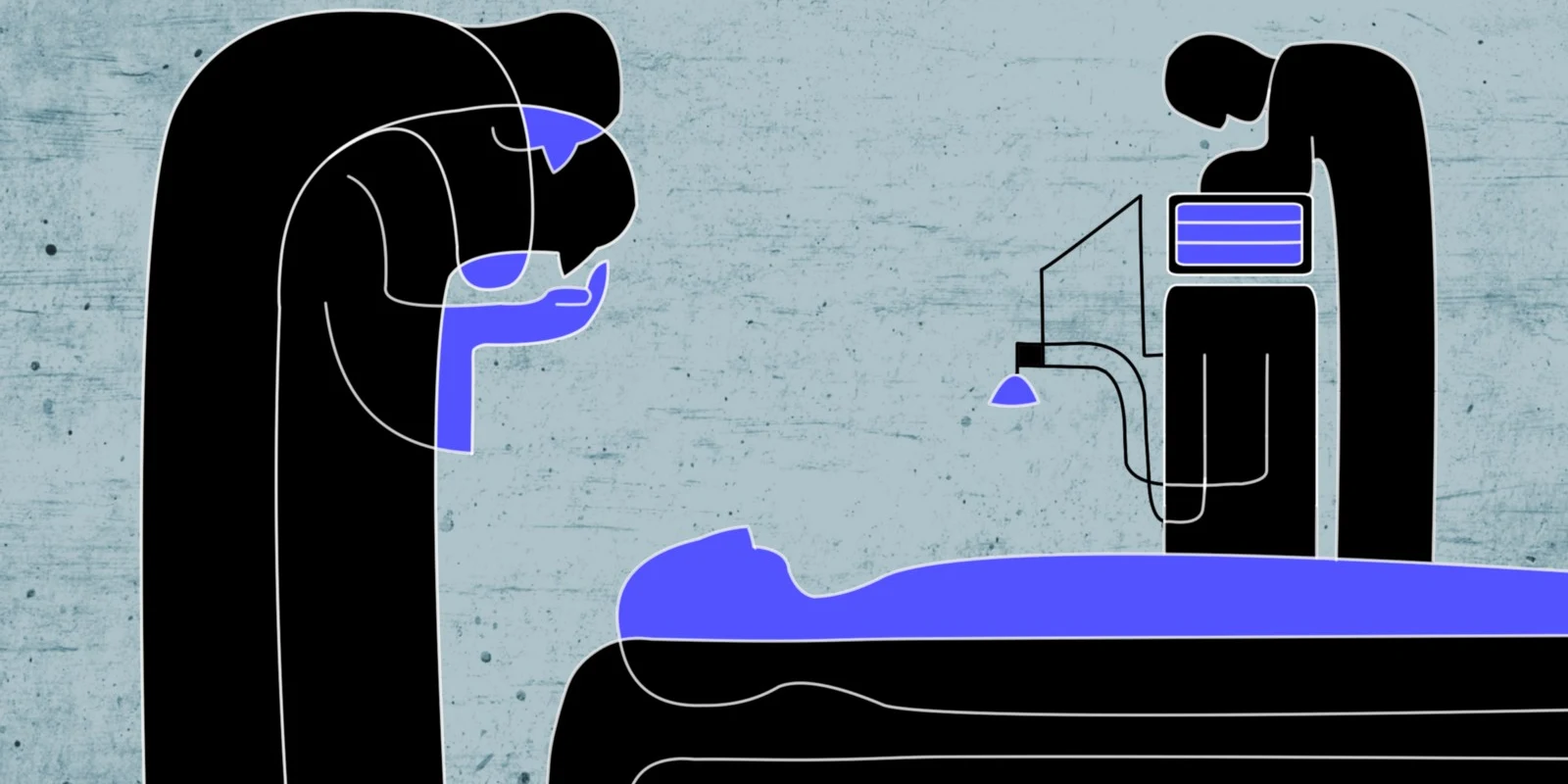

One week earlier, I was assigned to an overnight admission, a patient I would later know as Mr. Walker. He had advanced cancer that remained recalcitrant to chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery. He was transferred to our care for nausea and vomiting, discovered to be an intestinal obstruction from the tumor. Before me was a pale, gaunt man in his eighties with sparse patches of white hair almost glued to his scalp. Apologetically, I placed my hand on his shoulder to wake him. Before his eyes fully opened, he offered his hand to shake mine, a reflex which at one time must have been a deliberate action.

This routine continued for a few more days until one more morning when I asked about his family. After a long pause, he said, “I am in so much pain and I just want to die, but I don’t want to leave my wife here by herself.” I felt privileged to have earned his trust, that after all this time, it would be me he had chosen to confide in. Yet, I found myself paralyzed with a profound sadness. While his hesitation to be the commander of his own care brought me great unease, I sympathized with his qualms. Still, I offered the option of discussing end-of-life care with palliative care physicians, which he thought aligned well with his values.

Shortly before a family meeting where he planned to share his decision with his loved ones, I stopped by to check in on him. He proceeded to tell me a story of two brothers, each of whom carried a heavy wooden log on his back before embarking on an arduous journey. The first brother found the log too onerous to bear and chipped off a few pieces each day. The second brother, despite the pain and agony, persisted, until one day, they approached a tenacious river. The first brother, whose log was irretrievably compromised, perished while the second brother fashioned a raft and continued his journey.

As humans, we have a natural inclination to seek meaning, and I felt compelled to adapt his story to the immediate context. I would like to believe that Mr. Walker thought of himself as the second brother, battling his disease with a relentless energy until he felt the time was right. Yet, I knew he questioned whether his decision to discontinue life-prolonging treatments was akin to the actions of the first brother. I was also aware that my attempt to mold the concept of end-of-life care into a binary construct was intrinsically flawed. The constantly evolving goals of care cannot be addressed using a blunt, catchall framework, and as clinicians, we should respect patient autonomy beyond our desire to cure.

As Mrs. Walker nodded to her husband’s request to continue his journey, the two of them embraced once more. Relieved, Mr. Walker visibly sunk deeper into the misty twilight of his delirium, its gravity now perceptible in the air. The nurses, palliative care staff, and I then ceremoniously choreographed a battle against time as we quietly assembled a makeshift cot for Mrs. Walker next to her dying husband. Paying our respects, we took a few steps backwards before turning our backs on the patient we couldn’t save, and slowly but with unspoken purpose, we walked out of the room.

Names have been changed to protect patient identity.

David is a fourth-year MD/MBA Candidate at Tufts University School of Medicine, previously a research fellow in the Department of Dermatology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. His NIH-funded research is focused on improving dermatologic care through quality improvement.