Code blue 10 West! Code blue 10 West! Code blue 10 West! The red light coming through the western windows forewarned of a hot and tumultuous sunset. The second we heard the announcement, my entire team dropped everything, stopped midsentence, and flipped, robotically, the on/off switch that allowed us to access the part of our brain trained to perform extraordinary measures to save a life. There were no words, no thinking, no pause, and no hesitation; only muscle memory — neurologic synapses that had been molded over the years to fire automatically in case a child’s heart stopped beating. As dozens of clinicians gathered around the bed, the hierarchy and protocol were established instantaneously: a team leader, airway, chest compressions, medications, and so on and so forth. Like a computer, we followed a well-studied and established script.

For the code team, there was no time for emotions. We were professionals. In fact, so great was the emotional distance between the physicians and the family that two designated nurses took on the role of helping the mother weep as she watched her baby pass away. Observing from the outside of the room, I followed the protocol on a little red card that I always carried in my pocket. As a student, I was in the midst of programming my brain and my body so that, with each moment, I would grow closer and closer to becoming the perfectly robotic code leader that I ultimately needed to be. The team followed the resuscitation procedure step by step, word by word, breath by breath, with no room for flaws. This team, this machine that was born of individual clinicians from all over the hospital coming together, had to work seamlessly, like the wheels of a clock, taking measured moves, while painfully feeling each second resonate — a heavy step toward a hopeless ending.

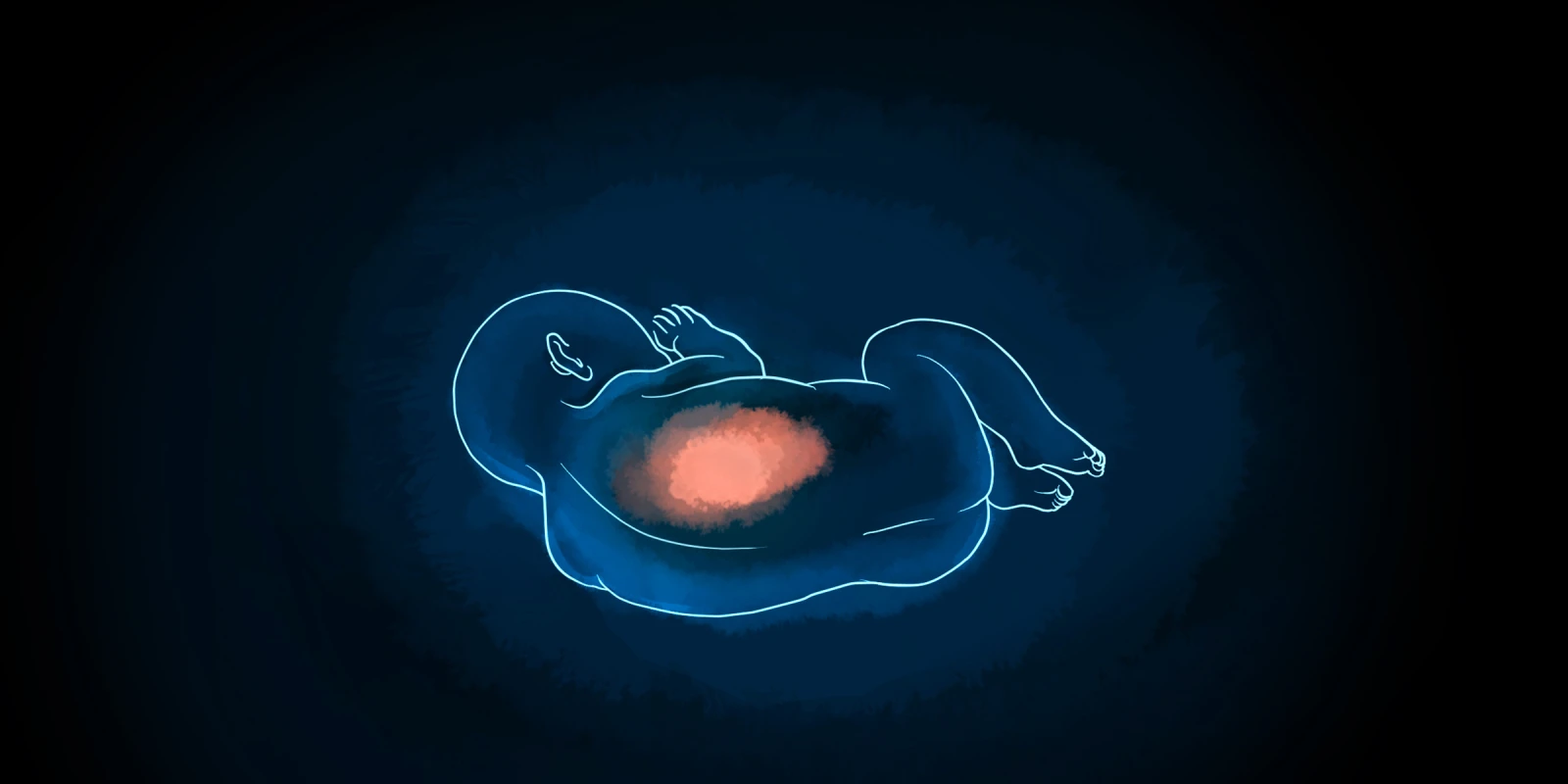

In spite of our knowledge and perfectly calculated dilutions of epinephrine, tidal volumes, and chest compressions, fate would intervene. Each second weighed upon us like lead, yet the hour that had passed seemed ephemeral. The hope and optimism that we entered the room with vanished into helplessness and disillusionment. We tried to play God but were forced to quit. Starting was easy; stopping seemed impossible. Indeed, ending the program, turning the switch to off, and transforming back into human bodies overwhelmed by emotion proved to be more difficult than performing CPR on a 4-month-old baby. It was a struggle, and we yearned to remain the robots who would emotionlessly continue the protocol, trying indefinitely and refusing to accept the inevitable reality of death. As we dispersed from the bedside, the parents’ shriek at the sight of their lifeless child pierced our bodies like a sharp sword, shaking our reality and waking us up from what seemed like a dream.

Without a word, my team and I returned to rounds for the patients who needed our full attention and emotional presence. As we entered each room, our faces lit up for our patients and we joked about the colorful cartoons on TV. We were not yet human. We continued to be professionals trained to compartmentalize emotions so as to give every patient a fair chance. Many minutes passed, perhaps even hours, before we eventually gave in and broke our shields to face the heaviness of our thoughts. It was only then that the members of the team surrendered to sadness, crying, and mourning. We hugged each other, as if through human contact we would reenter the circle of life, share our pain, and regain the strength we momentarily lost. Was this a sign of weakness? Were we losing hardheartedness in the face of feelings? That night, we had transcended human nature and metamorphosed from clinicians to robots, back to humans, and finally to clinicians. Yet it was only during this latter state of being emotionally overwhelmed that we were able to connect with the parents, cry along with them, and offer them the comfort they needed. We allowed ourselves to suffer and be genuine with a family whose emptiness was palpable.

It was only the first month of my third year of medical school, and I had already experienced birth and death and become keenly aware of the empty space between these extremes that would undoubtedly, over the years, fill in with stories. After having spent my entire life at a desk learning science, I had to “learn emotions,” to learn how to seamlessly intertwine the demands of being a doctor with being human. Many years have passed since this experience. Yet the traumatism of that moment molded me forever. As I mentor medical students now, I am poignantly aware of how fragile the mind and soul of a student is and how easily a blank page can be filled with good and bad stories. Death never gets easier. Processing it does. But learning to be a physician is as much about gaining the knowledge as it is about exploring human nature and emotions.

Ioana Baiu is currently a chief resident in surgery at Stanford University, after having previously completed a pediatrics residency at Boston Children’s Hospital. She is pursuing a career in cardiothoracic surgery.

Illustration by April Brust