As a psychiatry resident, I am embedded in many simultaneous and overlapping systems of care. Without navigating those systems from the patient’s perspective closer to the ground, however, it can be difficult to know whether they are working in practice. In a city like New York where I am training at Mount Sinai, the endless menu of institutions and programs can feel daunting. And conversely, in a small town or less populated area, the options for patients may feel more constricted and limited.

The other week, I received a call from an old friend in crisis. She said she had been feeling depressed and was having thoughts of ending her life. She was concerned she might actually act on her thoughts this time. She had struggled with depression for the past few years, and it all seemed to be coming to a head at a moment when she couldn’t afford to take a step back. She had been using a combination of cocaine and cannabis to simultaneously get through the work day and fall asleep at night over the past year, and her control over her situation was beginning to fray.

My friend had been admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit in the suburbs outside New York City for suicidal ideation a few years prior. Finding it unhelpful, she was loath to try the same approach again. She was also worried that a voluntary inpatient admission would grow into a prolonged involuntary stay, causing her to possibly fall behind or lose her position at work.

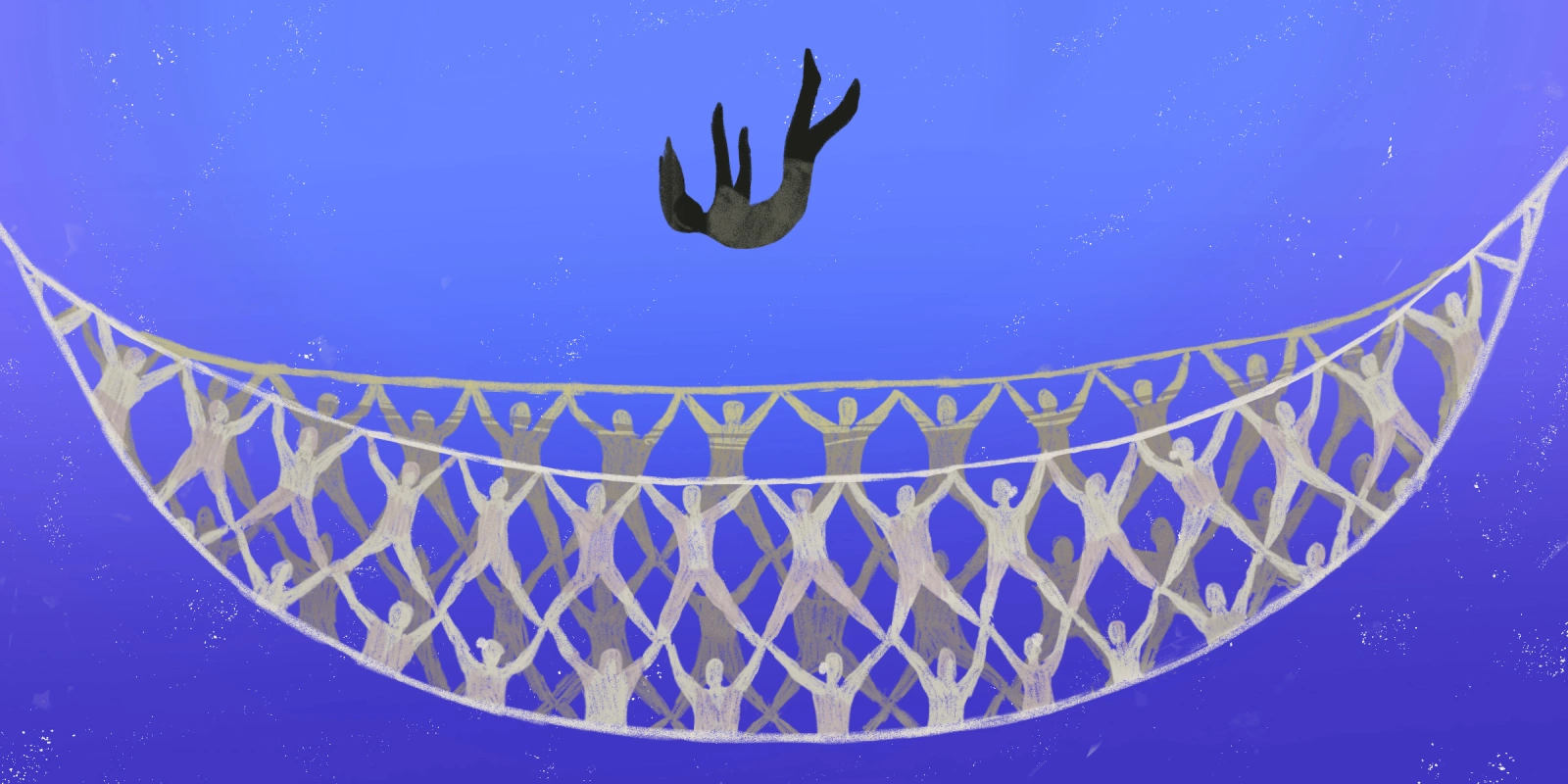

I acutely felt my friend’s bind — inpatient care can feel restrictive while outpatient care can feel too loose and insecure. What if my friend fell into a crisis overnight or over the weekend? And how would she face the added pressure of her addiction by herself at home? Psychiatry can feel like it offers a binary approach to treatment: someone is either on their own with outpatient follow-up, or they risk temporarily giving up their freedoms to pursue inpatient treatment.

As someone training in the field, I had assumed I would be well equipped to offer her the sound professional guidance she needed. Instead, as her friend, I came face to face with a harder reality that we all sense every day — that real gaps exist in our mental health system.

Patients with both an acute exacerbation of a mental health diagnosis and an underlying substance use issue often find it especially difficult to establish proper care. Moreover, dual diagnosis patients make up a significant part of the psychiatric patient population. One study estimated that adults with a dual diagnosis constitute 25.8% of those with any mental health disorder. Many mental health clinics, including outpatient clinics staffed by residents like me, often avoid treating patients with active dual diagnoses as they believe substance use needs to be addressed first to avoid interfering with treatment. However, some addiction clinics focus primarily on drug rehab and are not always as well equipped to support patients experiencing an acute mental health crisis.

A middle option for someone like my friend does exist, namely, partial hospital programs with dual diagnosis treatment — but these often place a heavy emphasis on groups, and some programs adhere to a rigid approach to addictions treatment. Not all patients are comfortable in group settings, and not all addictions present in the same way. And while dual diagnosis programs do exist, they are often full or difficult to access. In the case of my friend, she found one possible dual diagnosis intensive outpatient program with an opening, but after an intake interview, she found their approach to be relatively rigid and she grew worried they would be judgmental and dismissive.

Inpatient options can feel equally daunting, particularly for a patient who makes the choice to voluntarily come into the hospital. And insurance plans are often only willing to reimburse a few days or weeks of higher levels of care. Outside the hospital, though, the patchwork of outpatient programs, therapists, and care models can be difficult to navigate for even the most savvy of patients.

I had known all of this conceptually as a psychiatry resident in training, but it was not until I faced this predicament in conversation with my friend that I felt the challenges of our mental health system more viscerally. The models of care we currently have leave many patients feeling stuck between imperfect options.

Despite these challenges, promising innovations are emerging within the field. Some psychiatry departments, including my program at Mount Sinai, are opening up respite facilities in the form of units with Extended Observation Beds to provide patients with short term monitoring and a needed reprieve from isolation at home in a time of crisis. Additionally, Comprehensive Psychiatric Emergency Programs serve as new versions of psychiatric emergency care where patients can stay for up to 24 to 72 hours for assessment and treatment. For lower-income patients in some localities, crisis stabilization units act as another option for short-term acute care. However, real gaps in care remain. These options don’t exist everywhere, and patients are often discharged after just a few hours due to limited capacity and funding.

What would a solution look like? In large cities like New York, where a vast shelter network often acts as the de facto respite of sorts, the system could greatly benefit from specific respite centers designed to properly treat for short-term crises. As a society, we need to allocate more funding toward sub-acute mental health treatment and residential care models that include voluntary options for patients. These programs exist in some communities, but they often serve wealthier clientele who are able to cover the cost. Psychiatrists should work with policy makers to establish and fund more robust intermediate-level treatment facilities. If these programs divert some patients from entering the criminal justice system, municipalities may even save money.

In the case of my friend, she went with a bespoke option — she found a weekly therapist recommended through a peer. The therapist was willing to take on her case despite the safety risks, with weekly visits that included medication management. The catch? She had to pay out of pocket. The outcome left me wondering how patients in a similar bind with less social capital or less familiarity with health care options would fare.

At present, we don’t have a mental health care system in America. Instead, we have a hodgepodge of programs and resources. An alternative to our approach may be one similar to Canada’s, where I studied medicine. Our northern neighbor maintains a single-payer health care system with an integrated care network where inpatient psychiatric hospitals, outpatient services, and mental health housing are uniquely organized under the same provincial governing body. It is incumbent on psychiatrists to put ourselves in our patients’ shoes and consider what the current landscape looks like from their perspective. We should ask our patients about their experiences across the spectrum of care and collaborate with other clinicians to identify existing networks of resources — be they respite centers, crisis response teams, or affordable short-term outpatient interventions — for patients in moments of crisis.

Rarely in medicine does the gulf in experience between reimbursed care and self-pay options feel as stark as in psychiatry. If we expect to see new models of care flourish in a sustainable way, patients, clinicians, and policy makers must advocate for insurance companies to better reimburse novel forms of acute and subacute treatment. Patient navigation can sometimes feel like an afterthought, but it is often central to ensuring a patient gets the help they need. As psychiatrists, we have to combat our own field’s learned helplessness and look beyond the status quo if we expect to build a truly functional mental health care system.

What would it take to build a mental health care system that would work for all patients? Share your thoughts in the comments.

Dr. Brendan Ross is a psychiatry resident in New York City. He enjoys reading, writing, and spending as much time as possible outside. Dr. Ross is a 2025–2026 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

Patient anecdote used with permission.

Illustration by Diana Connolly