I was the woman’s doctor when her son was born and when he died. He arrived in the middle of the night, five months too early. She lay quiet while he slipped from the depths of her body into my hands. I remember her husband by her side, but only as a silhouette.

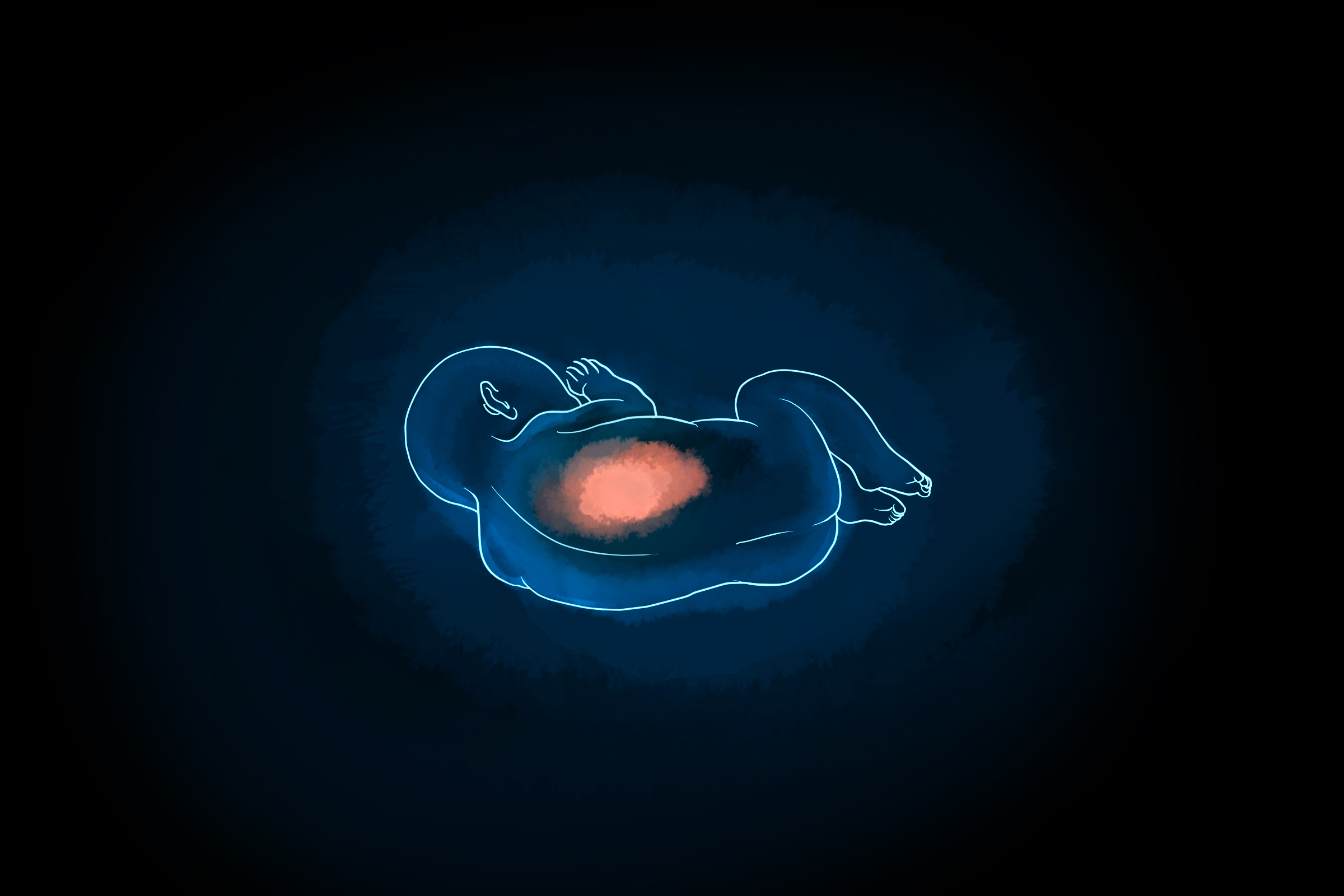

The baby’s skin was red and translucent, almost luminous, revealing a network of conspicuous blood vessels that coursed through his body like the veins of a tulip. His eyes were fused shut. Lanky limbs fell from his torso like twigs. Knobby, thin, and disproportionately long fingers and toes extended from his feet and hands. Though he would soon die, he entered the world alive.

In contrast to most babies I deliver, his delivery occurred in a dim room with only a single light. I did not encourage his mother to push. I did not count to 10 as she held her breath and bared down. I did not hold up her son in celebration, then place him on her chest where he’d cry and root. Instead, I held him — the entirety of his body resting in my palm — as he offered subtle movements, echoes of life, his chest rising and falling, head turning, mouth gaping.

I placed two clamps on his umbilical cord and then cut him free from his mother, severing his lifeline. His lungs were too premature to transport air. His brain, too fragile, would soon bleed. The thin and tenuous umbilical cord rested between his mother’s legs, still attached to the placenta inside her uterus. It was the width of a shoestring. If I tugged on the frail tether to facilitate delivery, as I would if the baby were term, the tissue would tear, break, and then avulse. I worried that the short gestation precluded the natural process of placental separation and spontaneous expulsion, the woman’s uterus not prepared to release the organ. I feared that if I waited, her cervix might close, further complicating the situation. I reached into her pelvis, my arm buried to my elbow, to force my fingers between the placenta and her endometrium. I pulled the fleshy mass from her vagina. But as I proceeded, she cried in pain. When my attempts appeared futile, I decided we should go to the operating room, where an anesthesiologist could offer her relief.

I could have waited — most physicians would have waited. Perhaps her placenta would have delivered without intervention. Perhaps reaching into her pelvis after she’d had time to bear witness to her son’s life presented no risk and was the humane choice.

But I was a second-year resident. I wanted to assert my authority, to be decisive and not afraid. I believed demonstrating my strength meant making choices. I believed I would save the woman from a more complicated procedure, bleeding, or infection. Blinded by the drama I had created around the moment, I believed there was nothing to lose by expediting the process.

When the nurse and I pushed the woman’s bed from her room, fluorescent lights intruded on my senses. As we moved through the hallway, the woman appeared confused but asked no questions, mounted no protest — she trusted me. But I had forced her to leave her son dying in the delivery room, his body swallowed by a blanket made for a baby seven times his size.

The operating suite was a stark, frigid, and busy space. The walls were unadorned and the floor was concrete. The objects in the room – equipment, clamps, knife, bed – were geometric, with squared corners. The scent of antiseptic mingled with the paper from my surgical mask. As the nurse and I wheeled the woman into the room, an anesthesiologist organized medication and tested equipment. Large, round lights hung from the ceiling, hovering like spaceships. The scrub tech counted steel instruments with the circulating nurse. A baby warmer waited in the corner, but there would be no baby to warm.

The woman maneuvered herself from her hospital bed to the operating table, scooting like a salamander – hips, shoulders, hips, shoulders. I placed her legs into stirrups the color of highway stripes, exposing her most vulnerable parts. Her baby’s umbilical cord hung from her vagina. The attending physician, the senior doctor on call, entered the room. I had woken him to say we were headed to the OR to surgically remove the woman’s retained placenta. Confused, he asked how long we had waited for the placenta to deliver. Only a few minutes, I said. He asked if she was bleeding. I said she wasn’t. Was she in pain? No. Then he asked why we were doing the procedure. What was the hurry? But though the decision to extract her placenta was hasty, it wasn’t exactly wrong; the team had already set up for the procedure, so we continued. While he and I discussed the case, the woman’s husband watched her son die without her. She never held her baby while he was alive — the little one died while I pulled and scraped the woman’s placenta from her body.

The next morning, I signed out Labor and Delivery to the incoming doctors and nurses. Gathered around a conference table in a small room, we discussed the patients who had been admitted overnight. Computer monitors hung near the ceiling and blinked with fetal heart tracings. The lights gave everyone in the room a yellow hue. The day team had coffee in hand, wet hair fresh from the shower, and they smelled of soap and shampoo.

I presented my patient. I explained what had transpired overnight, believing I had made the right choice. I was the wise hero. But the incoming resident swiveled in his chair to face me. “You should never do that,” he said. “Never. Do you know what she lost because you couldn’t wait?” In that moment, with those few harsh words, I stopped seeing the woman as a patient and she became a person — a mother.

Fifteen years later, I can’t remember the color of her hair, whether she named her son, or how long he lived. But I remember what my haste, my desire to be strong and decisive, stole from her. Now, when I think of her, a discomfort pushes at my insides as if pain, grief, and guilt are expanding into a mass larger than my body, greater than my capacity to contain them, more enormous than the grace to forgive myself.

I wish I could apologize. But what would I say? Would I explain that she lost that time with her son because I wanted to demonstrate control, competence, decisiveness? Would my explanation offer comfort? I can’t know because I will never find her. Though I recall my offenses, I did not bother to remember her name.

Previously published in Booth: A Journal.

Illustration by April Brust