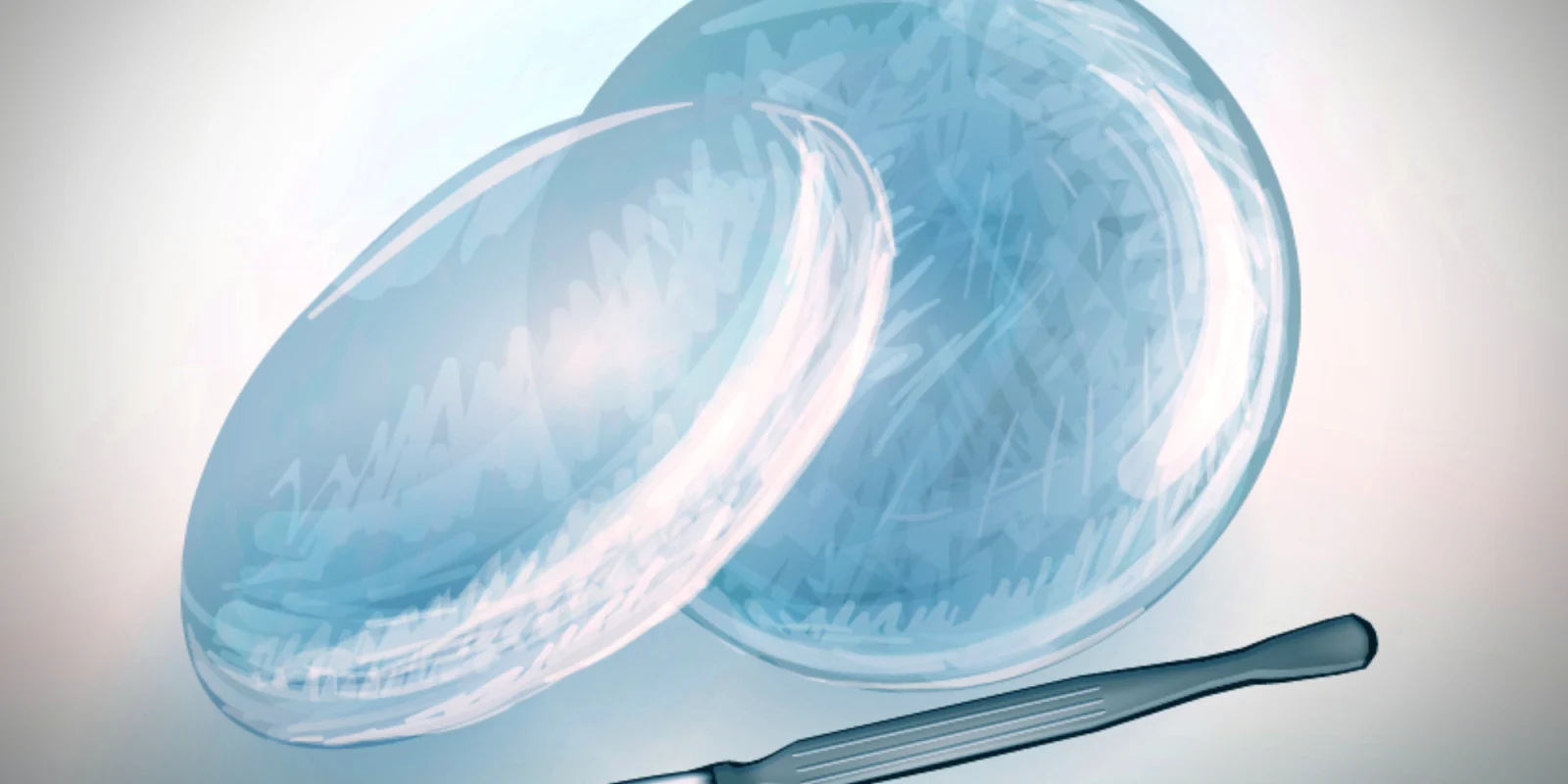

![]() With the FDA’s recent hearings on the safety of breast implants, plastic surgeons who have been in practice long enough are experiencing a sense of déjà vu. After a 15-year ban, silicone breast implants were given conditional approval in 2006 on a split Advisory Panel vote. Now, concerns about an association with implant texturing and a rare tumor called Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (BIA-ALCL), in addition to a vaguely defined syndrome dubbed “Breast Implant Illness” has all implants under the microscope again. But turning the mirror back to the regulatory process itself finds more contradictions and paradoxes than clarity.

With the FDA’s recent hearings on the safety of breast implants, plastic surgeons who have been in practice long enough are experiencing a sense of déjà vu. After a 15-year ban, silicone breast implants were given conditional approval in 2006 on a split Advisory Panel vote. Now, concerns about an association with implant texturing and a rare tumor called Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (BIA-ALCL), in addition to a vaguely defined syndrome dubbed “Breast Implant Illness” has all implants under the microscope again. But turning the mirror back to the regulatory process itself finds more contradictions and paradoxes than clarity.

Let’s acknowledge up front that for a long time, implants weren’t very good, patient education was limited by a general lack of clinical data, and long-term complications were too common. But despite high rates of capsular contracture and implant rupture, these were not what led to the moratorium that left them in regulatory purgatory for such a long time. A speculative association of silicone with cancer, autoimmune disease, and various symptom complexes led to a cavalcade of litigation culminating in a class action lawsuit against Dow Corning and implant manufacturers. Jurors openly admitted that even when shown evidence that silicone had no causative relationship to the condition, they would award plaintiffs out of sympathy. (1) Lawyers came to refer to this as “phantom risk.” (2) Silicone, meanwhile, remained on the FDA’s list of approved products for injection into the eye for treatment of retinal detachment (as it still does.)

During the moratorium, the use of silicone gel implants was restricted to clinical trials on breast reconstruction patients, most of whom had undergone mastectomy for cancer, while augmentation patients could receive saline implants. Because reconstruction has higher complication rates, this ended up skewing the data when silicone implants were presented to the panel for general use. Silicone toxicity having been refuted, (3) problems such as capsular contracture remained a leading concern. Implant surface texturing designed to modulate the process of scar capsule formation appeared to provide some benefit. With aggressive enough texturing, implants could be “anatomically” shaped because they would theoretically maintain their orientation by adherence to the capsule. In countries outside of the U.S., textured implants became the most popular choice. When FDA clearance was granted for gel-filled implants, plastic surgeons in the U.S. saw patients opting overwhelmingly for smooth. In part, this was because the shaped textured devices from Allergan (previously Inamed, before that McGhan), the dominant player at the time, remained off limits while upstart Sientra was given a thumbs-up for theirs despite shorter-term data.

Besides implant texturing, a number of approaches to prevention of capsular contracture were tried during the saline implant era, many of them based an increasing appreciation for the role of bacterial contamination. Pocket irrigation with Betadine (povidone-iodine [PI] 10 percent solution, one percent available iodine [Purdue Frederick Company, Stamford, CT] was proposed in the 1990s and some surgeons thought it might help to add it to the saline fill at the time of implantation. For reasons later shown to be unrelated, concerns were raised about whether this could contribute to implant rupture. No correlation of Betadine irrigation and implant deflation was ever documented, but it did appear to lower the incidence of capsular contracture. The FDA nevertheless moved in 2000 to specifically prohibit it in the Directions for Use (DFU) document for implants. Betadine irrigation became off-label.

It is now widely accepted that bacterial biofilms are implicated in most cases of capsular contracture, and are pointed to as a factor in the Breast Implant Illness syndrome, though this has not been documented. We are seeing patients come in specifically asking for implant removal with en bloc capsulectomy, convinced that the capsule is part of the problem. With BIA-ALCL, plastic surgeons were not caught off guard as we were in the early 1900s; I first saw a presentation on the subject in 2011. An intensive effort followed those early reports, and by the time of the FDA’s recent actions, a paradigm for its etiology, diagnosis, and treatment had been widely promulgated. Biofilms on implants from ALCL cases have disproportionate levels of Ralstonia bacteria, while non-ALCL capsules in contracture cases have mostly Staphylococcus spp. The thinking is that more heavily-textured implants have a larger surface area, hence a potentially greater bioburden. While the apparent decrease in capsular contracture risk with textured implants remains unexplained, the implications for prevention of BIA-ALCL are clear.

In response to a request from one of the manufacturers, the FDA eventually modified its DFU to allow Betadine irrigation in 2017. (4) So the effect of following the guidelines for all those 17 years would have been to raise the risk of complications of breast implants. Since the average time from implant placement to manifestation of ALCL is 8–10 years, most of the cases coming to light now were from the era soon after approval of textured implants but during the Betadine ban. Now we have a ban on textured devices, too soon after allowance of Betadine irrigation to see the effect. I’ll bet that the surgeons who defied the FDA’s explicit recommendation against Betadine are the ones with the best track record.

Dr. Baxter was once a clinical investigator for Allergan and Sientra and speaker for Allergan.

References

1. David E. Bernstein, The Breast Implant Fiasco, 87 Calif. L. Rev. 457 (1999).

2. Kenneth R. Foster et al., A Scientific Perspective, in Phantom risk: Scientific interference and the law (Kenneth R. Foster et al. eds., 1993).

3. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Safety of Silicone Breast Implants; Editors: Stuart Bondurant, Virginia Ernster, and Roger Herdman. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1999.

4. Jewell LM, Adams WP. Betadine and Breast Implants, Aesthetic Surg J, Volume 38, Issue 6, June 2018, Pages 623–626.

Image by Sunny_nsk / Shutterstock