In 1968, Rosenthal and Jacobsen introduced the concept that expectations in the classroom can positively or negatively affect students. This phenomenon was dubbed, “The Pygmalion Effect.” Since then, there has been controversy surrounding the topic. Other authors have argued that the data was insignificant or inconclusive. From my own personal experience, having been in school for over 10 years, I believe that the concept carries validity. Furthermore, I believe that it holds true outside of the classroom, specifically during medical training.

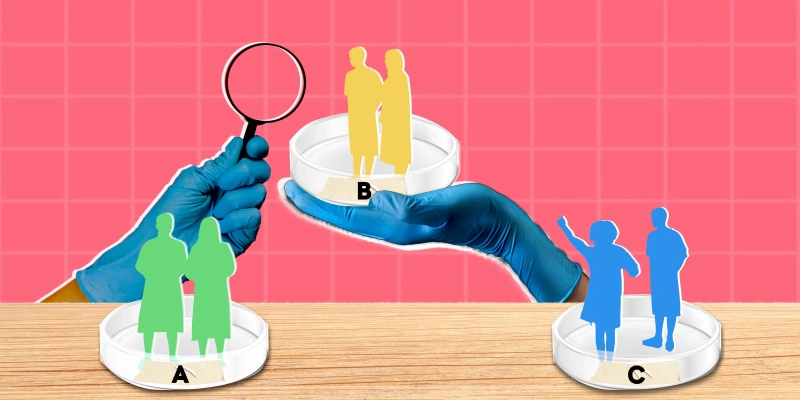

As medical students, you are constantly evaluated. Expectations are placed on you and you must fulfill these with confidence and grace, even if you have little direction or experience. You may have an excellent relationship with the first attending physician on service, who evaluates you and subsequently passes along his opinion of your performance as outstanding. The next evaluator may then simply expect that you will be able perform similarly such that your confidence is only increased. This could result in highly-rated evaluations all year long.

What if the first attending that you interact with doesn’t actually mesh well with you? What if he or she thinks that you are not meeting expectations of the rotation? What if you have something personal taking place simultaneously that is distracting you and not allowing you to perform at your highest potential?

This individual makes a judgment and passes it onto the next, who enters his or her interaction with you with a bias. He or she may not even realize that an opinion has already been planted and any interaction or performance, even if it is stellar, will be criticized. This inherent bias is continuously passed on even if you are improving. It will then be difficult for you to reverse the negative trajectory of your evaluation.

So, what are my thoughts? Attending physicians or senior residents should not pass down their impressions of junior trainees. These evaluations should be made without any potentially damaging information. Most recently, I started a rotation with a young attending physician who mentioned that she purposefully did not read the impressions and evaluations sent to her by the previous evaluator. She explained that she felt as though by reading these impressions, her opinions would already have been partially formed once she started on the team and she wanted to give everyone the chance to have a clean slate.

It was so refreshing to hear this kind of thinking. She allowed everyone the opportunity to wipe clean any past mistakes made. She opened the door for improvement and was encouraging to every single member of the team from the very start of her interactions. This kind of engagement and expectation is positive, supportive, and allows for true growth from all individuals.

Cherilyn Cecchini, MD, is a resident in general pediatrics at Children’s National Medical Center. With a future in hematology/oncology, her research interests include palliative care, communication during end of life care planning, and the concept of returning to normalcy near death. Dr. Cecchini has gained experience in narrative medicine by writing several pieces featured by the American Medical Women’s Association.