When I first met Julia, she had already been in the hospital for several days. She had been transferred from her community hospital for a bleeding placenta previa in the third trimester of her fourth pregnancy. The plan was to do an amniocentesis at 36 weeks to confirm fetal lung maturity, and then perform a scheduled cesarean delivery for a healthy baby. In the meantime, she would stay in the hospital so we could intervene rapidly if needed. Her only worry was that the baby would come too early, before her husband could be there. He was away for months at a time working on an offshore oil rig, and was making arrangements to get back home. “He is so excited for another boy, but a girl would be okay, too,” she said with a wink.

When I first met Julia, she had already been in the hospital for several days. She had been transferred from her community hospital for a bleeding placenta previa in the third trimester of her fourth pregnancy. The plan was to do an amniocentesis at 36 weeks to confirm fetal lung maturity, and then perform a scheduled cesarean delivery for a healthy baby. In the meantime, she would stay in the hospital so we could intervene rapidly if needed. Her only worry was that the baby would come too early, before her husband could be there. He was away for months at a time working on an offshore oil rig, and was making arrangements to get back home. “He is so excited for another boy, but a girl would be okay, too,” she said with a wink.

Julia wasn’t simply resigned to her prolonged hospitalization. She was content, happy even, to be there, because she truly knew it was what was best for her and her family.

Every day she got up, and got dressed. She read, kept up with current events, and stayed in contact with those important in her life, “George swam all the way across the deep end yesterday! Last summer he was scared to even put his head under the water,” she told me. It was as though she could not be confined to the hospital, and away from her home. Friends and family members would bring her three small children to visit when they could. The nurses and residents basked in the warmth of those family visits. We would play with dinosaurs, Power Rangers action figures, and Hot Wheels. They would help me find the baby’s heartbeat. We would eat Nacho Cheese Doritos, and Peanut M&M’s. We would read Oh, The Places You’ll Go, and they would fall asleep snuggled next to Julia in her hospital bed. “Some people think Doritos are messy,” she whispered. “But I don’t mind the crumbs. They remind me that my babies were right here in this bed with me.”

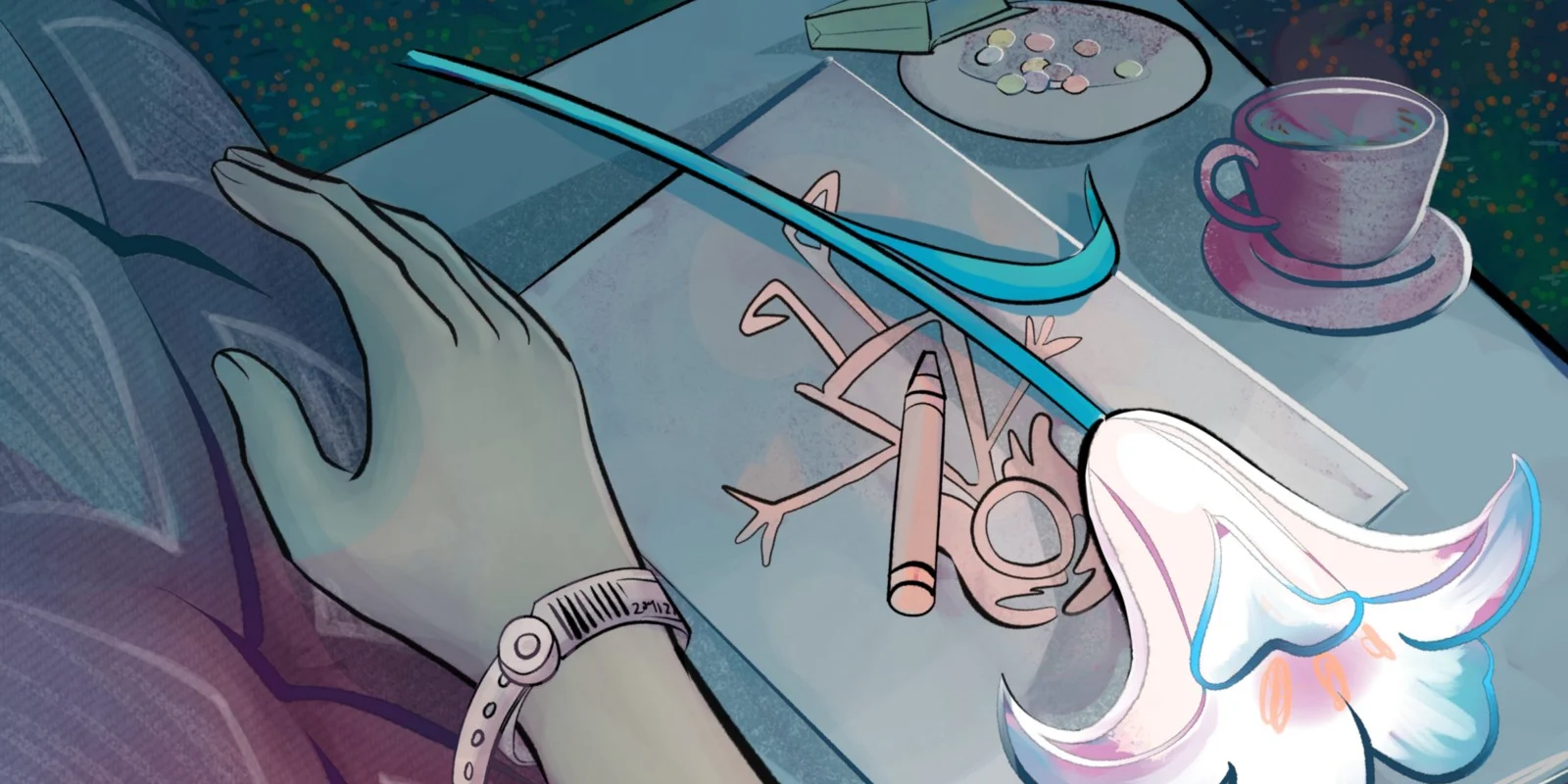

I enjoyed my daily visits to Julia’s room. She had made the space her own. There were crayoned pictures from her children on the walls. “I couldn’t make it to his little league game, so Tony drew me a picture.” said Julia. “And Michael found a turtle in the backyard!” Her favorite worn, quilted throw, that had once swaddled her other children, was draped over the end of her bed awaiting the new arrival, with her slippers peeking out from just beneath it. Her well-thumbed Bible lay on the nightstand. It felt homey.

When I stepped into her room, I entered a quiet calm separate from the rest of the bustling hospital. It was a space filled with goodness, and light. I found it therapeutic. I often planned my rounds so that Julia was my last stop so I could spend more time with her. Often, I would even return for a second visit before going home. I found myself looking forward to seeing Julia. She was warm, and welcoming, and I wanted to linger with her. I would sit down, transported to this seemingly different time and place, and we would chat. Never about anything in particular, but of all of life’s important details that make it so rich. She talked about her home, and her children, and about how she managed being a single mother when her husband was away. We wondered, together what it would be like to go into space as we watched a shuttle launch. As I got to know her over the several weeks she was in the hospital, I found that I had so much fondness and respect for this woman whose life choices were so radically different from my own.

Finally, the big day came. The amniocentesis results showed that the baby had mature lungs, and we were all set for delivery. I thought about how much I would miss seeing this woman, so full of grace, every day. I thought about how sunny and bright her room always seemed, and how I wasn’t sure if it was because of her south facing windows, or if it was that she herself made the room feel sunny and bright. I also thought how happy I was for her, and for her family. Her husband had gotten special leave, and had arrived the day before for the big event. The whole family was there, and the other kids were buzzing around with excitement for the arrival of their new sibling, and for the return home of their mother. There was an air of joy and anticipation throughout the antenatal unit, as we all neared the conclusion of this journey with our friend Julia.

In the operating room, we prepared for the procedure as we always do, and we were underway. There was a small cheer, and a sigh of relief as the new baby emerged and let out a robust cry.

Julia’s hand clutched at my hip. “She’s seizing!” the anesthesiologist said as monitor alarms began sounding. Julia stopped breathing; her heart stopped beating. We started resuscitation, all while trying to complete the operation. We coded her for 40 minutes more after she was closed. She didn’t hemorrhage. She didn’t succumb to bleeding from her placenta previa. Julia died of a rare amniotic fluid embolus. She never met her newborn baby, and never saw her beloved family again.

I sat at the desk finishing up the paperwork, the death certificate. “Where’s my mom?” an excited little voice asked.

It was Tony, Julia’s young son, my little buddy, with whom I had spent so many happy moments playing. I couldn’t find words.

There was a memorial service for Julia in the hospital chapel. Her family wanted everyone who had gotten to know her to have a chance to celebrate her life. My hope was to slip in un-noticed by the family. I sat in a back corner. I felt so guilty that we had failed her, and not been able to return her to her home. Her husband sat down next to me. I wished I could remember if he had been in the delivery room. He put his arm around me and thanked me for caring for his wife. I wish I had felt forgiven.

Emily D. Cline, MD is an Ob/Gyn practicing in Franklin, Indiana. Patient names have been changed for confidentiality.