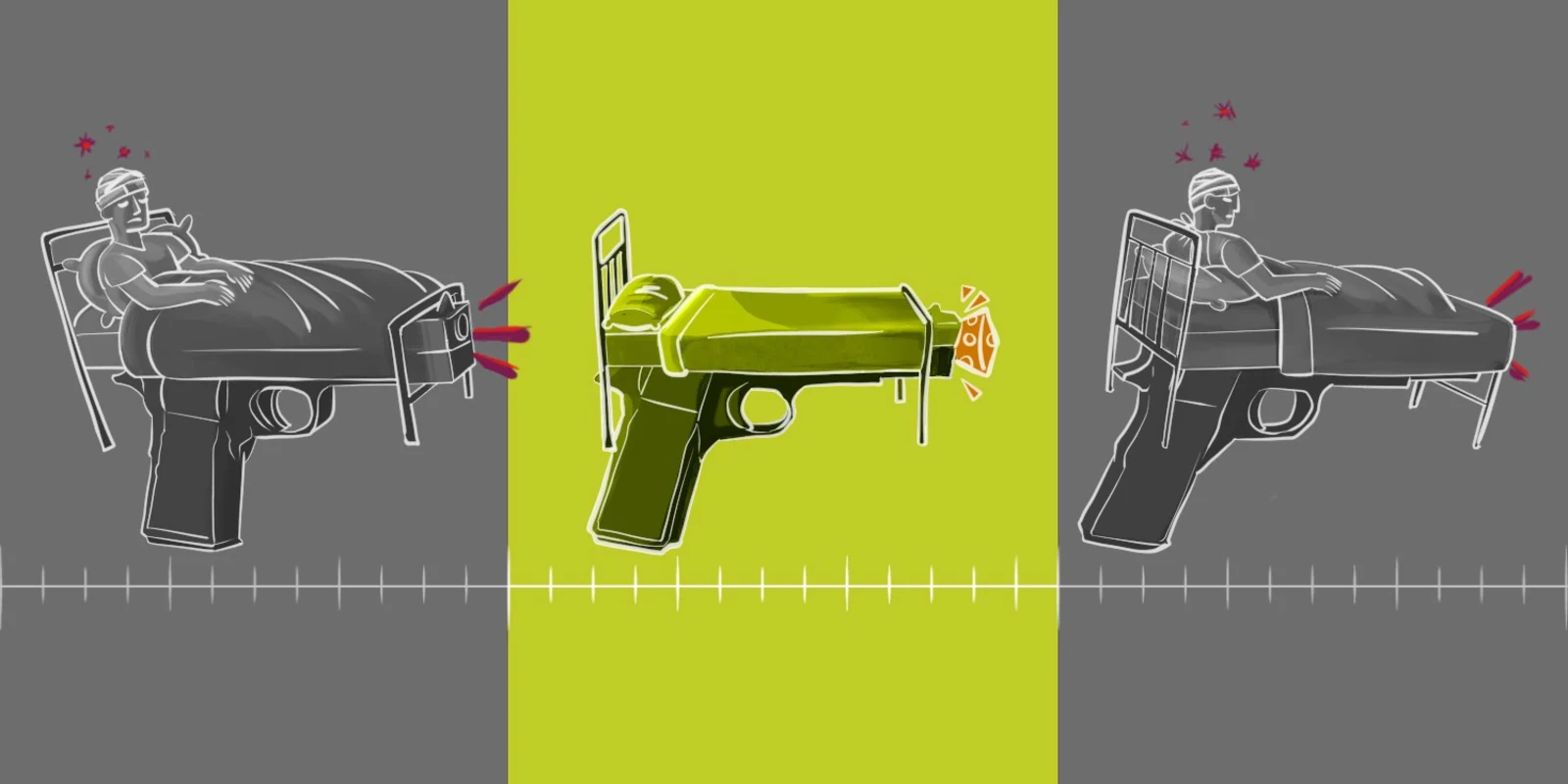

I spent the summer between the first and second years of medical school in the emergency department at Cincinnati’s major trauma hospital. More specifically, I spent summer nights there, studying the effects of interpersonal violence. Cincinnati is both a friendly city and a violent city. People say “Hello” when you pass in a corridor. At first, coming from Boston, this mid-West style of friendliness took me aback. At the same time, the Brady Campaign gives Ohio and Kentucky (which is just across the river from Cincinnati) a D and an F for gun laws. Both ranked into negative numbers on a scale of 1 to 100. Guns are cheap, plentiful, and easy to obtain. As you’d expect — gun violence is rampant. Firearm injuries happen with such frequency that there was a dorm on campus for military medical personnel who train in trauma medicine at the hospital. Think of it — the military finds American urban medical centers enough of a war zone that it is a staging area for their doctors and medics before deployment to the battlefield. In fact, gun violence deaths in U.S. cities each year vastly outnumber American deaths in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Like most medical students entering their second year, I had completed gross anatomy. I had interviewed patients in the hospital and I had shadowed physicians in their offices. In my life prior to medical school I had assisted veterinary surgeries but had never seen inside a living human body.

One evening, the trauma bay was radioed about an incoming teen male shot multiple times. Staff pulled on yellow paper gowns, gloved up, and the equipment was ready to go. From the parking lot, they radioed about severe chest injuries and massive blood loss but reported a pulse. A trauma attending readied a big metal box. Shortly after, the wide double doors swung open and the EMTs came in doing chest compressions on a young African-American male. I noticed how young and fit he looked. He would have been more at home playing outdoor sports than here on a gurney.

The surgeon and ER physicians assessed him — he was surrounded in a swath of blue and quickly naked and covered in blood. The lead surgeon in a skillful, powerful, and quick move sliced open the left side of the chest and soon a rib spreader separated his chest. In what seemed like seconds the surgeon’s hands were on the patient’s heart and he was surveying the heart and great vessels. He placed a clamp. He was looking for an injury he could repair. All the while around him was a blur of activity, the team trying to save the young boy’s life. There was no repairable intrathoracic injury. There was no return of cardiac function. Time of death was declared. That heartbeat in the parking lot was his last.

Most of the team disbanded and trickled back to saving other lives in the ER. The surgeon gestured to myself and another trainee. He invited us to look into the open chest. I was at the same time in awe at the lifesaving maneuvers I had just seen and horrified to see the open chest. The patient’s first injury was the gunshot but the open chest seemed another injury. There was the initial violation of the gunshot wound and then another one to try and save him. I had never seen a person operated on, I had never seen a still-warm body spread open, I had never seen a person die. It seemed like there should be some moment of silence or acknowledgement that here was a young vital life gone. But life just went on. I went home that morning and I don’t think I slept much at all. To this day I can vividly remember the whole scene.

It is reported that about 10% of traumatic thoracotomies survive to hospital discharge — it is a last-ditch maneuver. It has been said that it is the first step in the autopsy. There are criteria to apply to decide who gets their chest opened and who doesn’t. It is not a decision entered into lightly. I am glad there are people skilled in these life and death procedures. I am glad there are people who thrive and excel in this high-stakes environment. Hopefully I will never need their services but it is nice to know our ERs are ready with staff waiting should I ever need it.

Heather Finlay-Morreale, MD, is a board-certified primary care pediatrician working for Nashaway Pediatrics, a practice run by UMass Memorial in Sterling, Massachusetts. Her interests include mental health, mindfulness, and general well-being.