They are physicians, mentors, partners, mothers, sisters, friends, colleagues — but most evidently at the moment, they are heroes. I (virtually) sat down with five women physicians, at all points in their medical careers, who are working in several of the largest EDs in Texas, to talk about their experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic. What I thought I was going to walk away with was a better understanding of how the EDs were handling the largest health crisis in a decade; however, what I didn’t expect were these stories of incredible resilience.

They are physicians, mentors, partners, mothers, sisters, friends, colleagues — but most evidently at the moment, they are heroes. I (virtually) sat down with five women physicians, at all points in their medical careers, who are working in several of the largest EDs in Texas, to talk about their experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic. What I thought I was going to walk away with was a better understanding of how the EDs were handling the largest health crisis in a decade; however, what I didn’t expect were these stories of incredible resilience.

Doctors are finding that on top of dealing with the medical symptoms of COVID-19, they also have social obstacles causing ethical dilemmas in the care of their patients. All of these physicians I spoke with are practicing at county hospitals, meaning they are the primary caregivers for these large cities’ homeless, uninsured, undocumented, and underserved. Each one of them brought up the difficulty with patients experiencing homelessness. Discharging someone who is unable to self-isolate for the recommended 14 days brings an ethical challenge. Another physician spoke on how she personally was pushing for COVID-19 testing in patients who were being medically cleared for jail, as sending an asymptomatic carrier into such a crowded population would put hundreds at risk. Even for many patients who do have a home where they can quarantine, taking two weeks off of work is not an option. However, it is important to remember that these challenges are not specific to this pandemic, did not begin with this pandemic, and will not end with this pandemic. Systemic inequalities and disparities due to social determinants already existed in the medical system, but are even more apparent during this pandemic. “Our population doesn’t have any particular challenges that are specific to COVID-19, but COVID-19 has just shined a brighter light on them — whether it’s access to care or being able to follow up.”

Unfortunately, all of these aspects of life during COVID-19 are interconnected — medical, social, financial, and psychological. We have all been feeling the effects of social isolation, uncertainty, fear of infection, losing loved ones, the non-stop media coverage, etc. Combine that with the lack of access to mental health services in these underserved communities, and the psychological impact is amplified even more. Each physician noted that they have seen an increase in patients visiting the ED with psychiatric symptoms, in particular, anxiety and panic attacks. EDs are also seeing increased rates of decompensated chronic psychiatric illness like dementia, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia due to issues accessing care or paying for medications. It was obvious before the pandemic that America has a mental health crisis on our hands, and this fire is only fueled by this novel global situation.

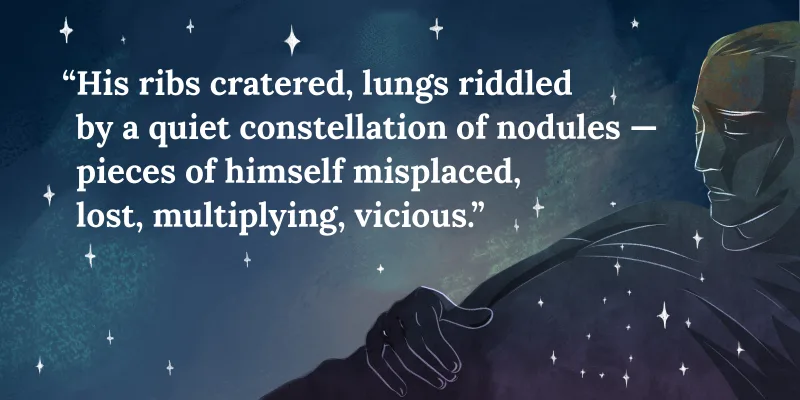

One cannot talk about mental health during COVID-19 pandemic without mentioning the sector of society that is perhaps experiencing the most trauma: our health care workers. One of the residents I spoke with said that the death of Dr. Lorna Breen, an EM physician in New York who tragically died by suicide in April (New York Times) “...was huge on us. That was a wake-up call that we need to check up on ourselves.” Residency is an infamously challenging time in the career of a physician, even without a global pandemic occurring. They are workers who, some even less than one year ago, went from student to doctor, and in this current situation they are now being thrust onto the front lines of the largest health crisis in over 100 years. This particular woman, who is two years into her residency, stated, “There were times before going to work that I sat in my car terrified, on the verge of crying. I was scared for my life, I was scared for anybody around me.” However, she also described bonding with her colleagues about these shared emotional experiences, and feeling very supported by the attendings at her hospital as well.

Two of the women I spoke with are mothers of young children, which comes with its own challenges during this time. One of them who has two daughters both under 2 stated, “It’s hard to not hug them, especially when they are super excited that you’re home. But it’s the new normal, so you get used to it and it becomes just another day.” Another mother and physician talked about the obstacle she has had with keeping her elementary school-aged children focused on their class Zoom meetings while she and her husband, who is also a physician, continue to go into work. Like many people across America, their home lives look quite different than they did even at the beginning of this year, but they cannot let it affect their work lives.

After speaking with these women, for me to use the word “inspired” is an understatement. When it comes to medical specialties, EM physicians have always been the definition of the “front line.” They are classically the first physician to see or touch a sick patient. There is no doubt that the highest risk of exposure to COVID-19 is placed on EM staff. The resilience that has been shown by physicians all across EM is undeniable. As one physician I had the privilege of speaking with told me, “You are often helping someone on the worst day of their life. It’s scary, but at the end of the day, it is what you signed up for when you went to medical school and when you chose emergency medicine. I love emergency medicine. I would never want to do anything else in my life.”

Image by Matteo Benegiamo / Shutterstock

Click here to see more perspectives on COVID-19 from the Doximity network.

Click here for up-to-date news about COVID-19 on Doximity.