In the rural county of Blount, Tennessee, where I live, the per capita income is approximately $38,000 less than the national average. Statewide, our obesity rates get us ranked a depressing 40th/50th in the nation. Further, Tennessee does not have federally funded Medicaid, but rather its own state-funded version called TennCare. When you mix poverty, obesity, and a state-run insurance plan that limits care access, the rate of preventable chronic disease tends to increase and concomitant diseases will oftentimes be present.

Among the working poor, a population common in rural East Tennessee, some of the most frequently occurring conditions are MASLD and non-alcoholic cirrhosis. There is surely a percentage related to alcohol, and in Tennessee binge drinking is reported to be around 15.1% for the adult population. That isn’t insignificant, but it leaves out some of the non-drinkers classified as obese. Remember that 40/50 stat I cited? It’s a lot of people.

As a GI NP, many of my patients are referred to me from either the local ER or occasionally primary care. Our primary care models don’t always allow for the in-depth discussion about MASLD that has to happen early and often. My usual clinic scenario is as follows: 58-year-old woman, BMI 40, type 2 diabetes; presented to the ER with complaints of belly pain. CT showed fatty liver; glucose on CMP was 170. No findings to explain belly pain on exam and imaging so she was sent home and referred to GI. She has been told to “eat healthy and walk to keep your sugars under control” for many years. She’s in danger of losing her job because she’s missing work due to this pain. She cannot afford her copays and bounces from urgent care to ERs when she feels poorly. She had TennCare during COVID, but was taken off the roles recently in our state’s effort to curtail costs, so she is now uninsured. Due to the disjointed care, no one picks up on the trending elevation in her liver function tests.

By the time she can come see me, she has had swelling in her belly and complains of bloat and pain on her right upper quadrant. This time all the liver function numbers are grossly abnormal, her bilirubin is 8, and she’s having a lot of upper GI symptoms related to her liver. The CT shows moderate volume ascites and nodularity. The ER doctor told her she has cirrhosis of the liver and she’s scared. She’s adamant that she’s not a drinker and she’s angry that it was implied with the diagnosis.

I would estimate about 3/4 of my patients who have cirrhosis fit this scenario. The concerning change I’m seeing is more and more 20–30 year olds sent to me for fatty liver findings. They are working hourly wage jobs or have a disability diagnosis and do not have work or insurance. Quite a few still live at home. They eat what is purchased with SNAP and their household income is usually social security disability income. These folks have insurance. Some are even covered in their parents’ plans from their jobs at the local manufacturing plant, which has good coverage. But they still need the household income to cover costs of transportation to appointments, missed hourly wages, and medication. And these health care costs drive them away from us, not closer.

The discussion I have with these patients takes into account many different aspects of their lives: their life story, food accessibility and affordability, and what their life is like now. Do they walk or do any formal exercise? How many hours a day are they sedentary? What’s their sleep like? How many people live in their home? That last question seems silly for GI, but it isn’t unheard of for nine people to live in a mobile home and share the income and food. It isn’t unusual for these young adults to live with their grandparents or to have been raised by them. Poverty is generational. The other thing to take into consideration is that according to the Appalachian Learning Initiative, 37.9% of adults in Tennessee read between a third and eighth grade level, and 21.7% read below a third grade level. When people cannot read, they will often struggle to comprehend materials or seek out information on their own from non-verified sources. It has been my experience that these patients tend to do what their parents did because it “worked for them.”

The things that public health experts tout as preventative care measures are often out of reach for this population. Eating fresh vegetables, fruits, and whole grains; buying organic; no seed oils; making their own meals from scratch; 150 minutes of vigorous activity daily; cold plunges; and don’t forget to strength train and avoid nicotine. This is an overwhelming list. I myself have the means, but I can’t even do half that stuff, because I’d need a therapist to process it all.

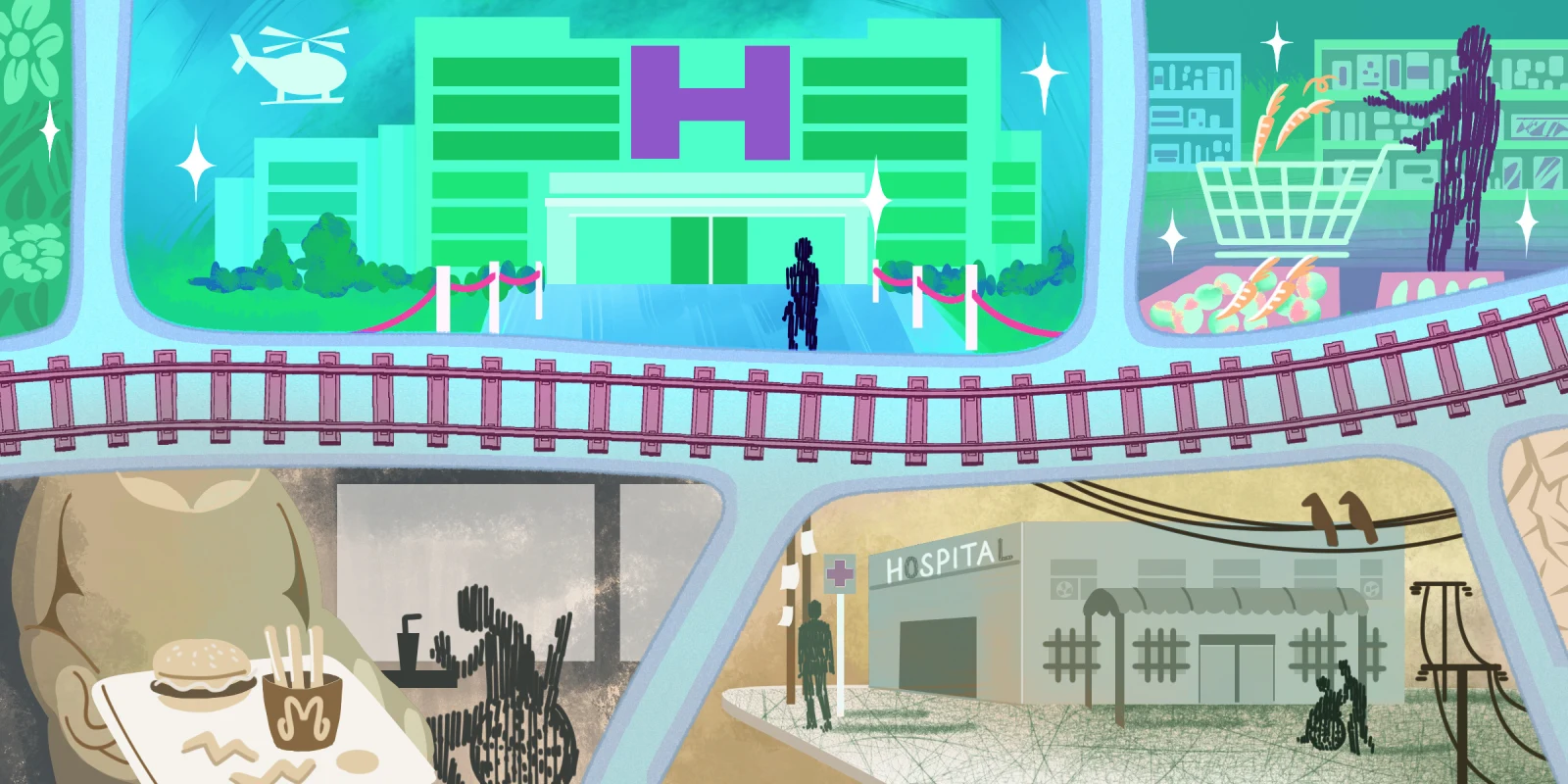

It isn’t news that poverty and lack of literacy are part of the social determinants of disease. We have a lot of both in East Tennessee. People visit here and see Dollywood, Pigeon Forge, and a thriving Downtown Knoxville and assume there is enough to go around in terms of wealth. The reality is starkly different. Our drug problems and overdoses have almost tripled and don’t seem to be going anywhere but up. Affordable housing is a pipe dream and while our population grows from people moving east to the mountains, the wealth gap is widening. This affects levels of chronic disease, which affects the cost of care. If you have no insurance then your medical debt can bankrupt you; if you do have insurance medical debt can still bankrupt you. Most people here (and certainly elsewhere) are one check from bankruptcy and homelessness. If you have our state insurance, then your care is limited by the plan and the medications you can get are limited; those new fancy ones for MASLD, don’t expect to get them ever; don’t expect coverage for GLP-1s. TennCare will pay for your gastric sleeve, but not the dietician or therapist to work through the food issues that got you to the point of having surgery for weight loss.

There are days I feel successful in helping people, but a lot of days I am fatigued from fighting a system that prefers to keep these fine people of Appalachia in their generational poverty and continues to feed the disease state and limit access to treatment. It makes me work hard, it makes me angry. We can do better. We have to do better if we don’t want multiple generations lowering the average age of mortality.

Writing to your legislators is something I would advise, not only nationally but locally. Tell them how proposed cuts to programs that benefit our patients’ health, like SNAP and WIC and school lunch, can impact their community. If you are able, meet with them and explain.

I also advise joining a medical society. The American College of Gastroenterology is the one that I belong to. They do advocacy in the national arena and have some influence with their size. Join your professional organizations and help get the word out.

Further, try to be proactive in how you talk to your patients. For example, ask them detailed questions about their alcohol intake. If they say “only moderately,” clarify. Their moderate may meet the criteria for alcohol use disorder. You can do this in a nonthreatening way and yes, talk about obesity. We know how to emotionally interview, we learned that skill, so use it. Be gentle and feel out how ready someone is to address the issue. If a patient comes in and says “I need help losing weight,” educate yourself about the medications that are easily prescribed and affordable.

Additionally, if you see kids in your practice, talk to them about healthy behaviors. This may not seem like a fix for the current influx of MASLD and liver disease, but we have to start early when we are educating about healthy eating and movement. Kids can bring this knowledge home and if we APPs echo the information in our visits, we can impact disease.

Also, consider using social media to link out to helpful information for an audience beyond your own patients. As a clinician, you have a bigger reach than you know.

Lastly, model healthy behavior. If you are making nutrient-dense food choices, staying active, and not preaching (people will shut you out immediately if you preach), then folks will catch on and will ask questions. Bring your knowledge out into the community — try to find local groups where you can show people how to grocery shop or cook healthy meals on a budget. You can even organize a club that walks or hikes regularly. These efforts don’t have to be elaborate. But they will make you and the people around you feel not only healthy and connected, but like you’re making a difference.

How do you cope with a system that's stacked against patients? Share in the comments.

Allison Falin is a nurse practitioner in Maryville, TN. She enjoys weightlifting, hiking in her nearby Smokies, and just being outside. She has practiced as a NP for 11 years and RN for a cumulative 27. She and her husband have three adult children and four dogs. She is on threads as @alliefnp. Allison is a 2024–2025 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

Illustration by April Brust