Whether it’s treating a heart attack or stemming a bloody wound, clinicians are familiar with acting under crisis. But what about when a fire is at the door of the hospital? For Dr. Joshua Weil, what he thought was a grass fire became a night he learned how to answer that question.

Late in the evening on Oct. 8, 2017, the smell of smoke pervaded homes across Sonoma County, California. Dr. Weil prepared for his shift as an ER doctor on call at Kaiser Hospital Santa Rosa. The night was hot, and the wind began to pick up. Dr. Weil and his wife examined their property and the surrounding Santa Rosa hills. The pair assumed there was a grass fire in the area, and Dr. Weil drove to Kaiser for his 11 p.m. shift.

The atmosphere in the hospital was tense. The smoky odor permeated the building, and the patients were reporting similar conditions around the city. An hour into his shift, firefighters and paramedics told Dr. Weil that every fire asset in the county was currently deployed. When he heard that, Dr. Weil told Doximity, “the hair stood up on the back of my neck.”

Around 1 a.m., a paramedic’s radio began broadcasting an address that caused Dr. Weil to pay attention: it was just a few miles from his home. As soon as he could, he called his wife and suggested that she begin preparing to evacuate — “just in case.”

Fifteen minutes later, Dr. Weil received a call from his neighbor, desperately screaming to evacuate. He called his wife, and his then 15-year-old daughter answered, screaming. In those harrowing moments, Dr. Weil tried to calm his daughter and ask what was happening with them. His wife let him know they were in the car, and when they were down the hill from their house, Dr. Weil instructed them to come to the hospital, which they did. Then he let the administrator on call know that his home had just burned down.

Dr. Weil was requested to join the campus command center as incident commander, as he had formal FEMA training and has helped in previous natural disasters. At that point, the staff was taking stock of the situation. “It was a little after 3 a.m., and the fire crews and police were on-scene and were [preparing] for the fire that was moving from the north toward us.”

Within a half-hour, a firefighter explained that they were using nearby land as firebreaks [obstacles to stop or slow the spread of a fire] to make a “last stand.” Dr. Weil recollected, “That phrase wasn’t exactly full of confidence.” So, despite the firefighter’s suggestion to shelter-in-place in the hospital, the command crew, including Dr. Weil, Area Manager Judy Coffey, and Physician-in-Chief Kirk Pappas, decided to evacuate.

“It’s a big deal to decide to evacuate; it puts everybody at risk,” said Dr. Weil. “[But] I did not want to think about evacuating the hospital as it was actually burning down.”

With the decision made, the command team contacted the county Medical Health Operational Area Coordinator, which organized ambulances to evacuate patients, but there were close to 130 patients to evacuate. He elaborated that the hospital had systems in place for a small number of patients, but “we didn’t have a system for organizing and tracking all our [123] patients who were being evacuated.” One of Dr. Weil’s colleagues began taking photos of patients’ wristbands to make sure they tracked everyone who evacuated. The city also provided buses to move the bulk of patients, while private vehicles with staff shuttled the rest down to another hospital. What should have been a 30-45-minute bus ride became several hours long, as city residents also sought to escape from the blaze. Despite the delay, there were, thankfully, no fatalities.

A little more than two years later, Sonoma County was hit with another disastrous fire. The Kincade Fire burned in a similar path and forced the Kaiser Santa Rosa command center team to consider evacuating again. This time, though, there were streamlined procedures: “We have a tag system in place. It’s a way of organizing patients and their needs in terms of isolation, whether it’s Clostridium difficile, influenza, or any other myriad of other contagious infections.”

Dr. Weil also relayed that they now have commercial products to help perform that tracking, have stocked up on supplies to help patients during transport, and have police escort options to help expedite travel out of the city. “We definitely learned a lot in 2017 and were able to apply it in 2019.”

There was also preparation for an evacuation by offloading patients preemptively. “We ask, ‘Who can we move now, safely?’ And we’ll move a couple of patients to some of our other Kaiser Permanente facilities like Kaiser San Francisco and Kaiser Vallejo. So [when] it was really time to go, we had far fewer patients in the hospital.”

But again, in 2020, there were two more fires in Santa Rosa: the Hennessey Fire on August 17 and the Glass Fire on September 27. These two blazes came with a new twist: a pandemic.

“The biggest thing is the requirements for isolation, particularly COVID-19, which … we got a little bit lucky. We didn’t pay too much attention to isolation requirements [in 2017]. We have photos of when we had everyone stage for evacuation and [the patients] were squashed together in the hospital entrance, and that would not be a COVID-19-safe setting,” Dr. Weil said.

Dr. Weil explained that his hospital has since reviewed their disaster management plans and included an alternate area for people who require isolation. “I was involved in a lot of conversations … in the forefront was how do we do that in a way that’s safe in the time of COVID-19?”

The long-term impacts on clinicians reaches beyond burning structures. The health effects of working in smoky conditions are dangerous. “I walked around for days breathing the equivalent of smoking two packs of cigarettes … I know that research demonstrated ongoing and lingering effects on COPD, asthma, and emphysema, which showed increased exacerbations and hospitalizations.” And then there is the toll such an experience takes on one’s mental health. Dr. Weil touched on mental health in the region, stating that there appeared “to be this underlying anxiety that permeates our community, especially during fire season.” But clinicians didn’t have to suffer in silence.

“The Permanente Medical Group did a huge amount of work supporting the mental health of the clinicians and employees.,” Dr. Weil added. He recounted that, on the second day after evacuating the hospital, he was pulled aside. “I was in the command center, and I barely slept. They said you need to go talk to somebody from employee assistance.” He pushed back, stating he needed to continue working. “Someone said, ‘Hey, you just lost your house, what are you going through?’ That was the first time I cried. It was the first time I let my guard down and looked at how to deal with that.”

After the fire, the support did not let up. “In the ongoing months and year, we put all kinds of support together in terms of helping people navigate the insurance and home building, navigating time off, and the need for mental health. So as organizations, Kaiser Permanente and The Permanente Medical Group really stepped up to the plate for that.”

And though it cost him his house to gain experience, Dr. Weil is now able to use that experience to help other hospitals, traveling across the country to spread awareness of disaster preparedness with his colleagues. “I’ve spoken at a number of conferences, some are more academic than others, but some of them are disaster collaborations … to spread the word on what we’ve learned.”

What would you like to read about? What do you think deserves more coverage? Share your suggestions here.

Dr. Weil is employed by the The Permanente Medical Group and has no conflicts of interest to report.

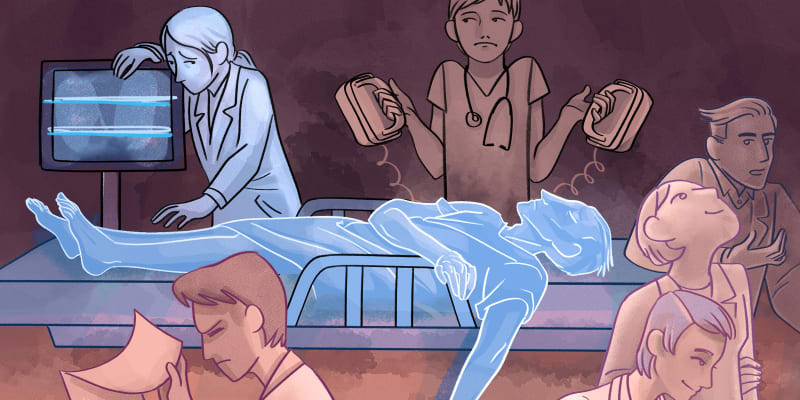

Illustration by April Brust