Resident physicians are viewed as a limitless resource, a collective body that can give and then give some more. Graduate medical training is an exercise in self-preservation; one that involves losing bits of oneself to make it through to the proverbial other side. This is not a novel idea; it is all too often a struggle that we lose our colleagues, our friends, too. With ACGME duty hour and wellness guidelines (1) viewed as challenges to the departments and hospitals we work for, there is no room for sincere acknowledgement of the emotional and physical labor that residents are expected to wring out 24/7.

The current system works to infantilize and wear down young doctors. In the face of retribution for advocacy, long working hours, and a veil of support from leadership, residents may be too tired, too weary, or altogether apathetic to find their voice - much less wield it. This conditioning remains salient as they venture forward into their careers where the status quo continues to be the modus operandi. The product is a pervasive disillusionment that perpetuates a culture of complacency in medicine. This makes change seemingly impossible.

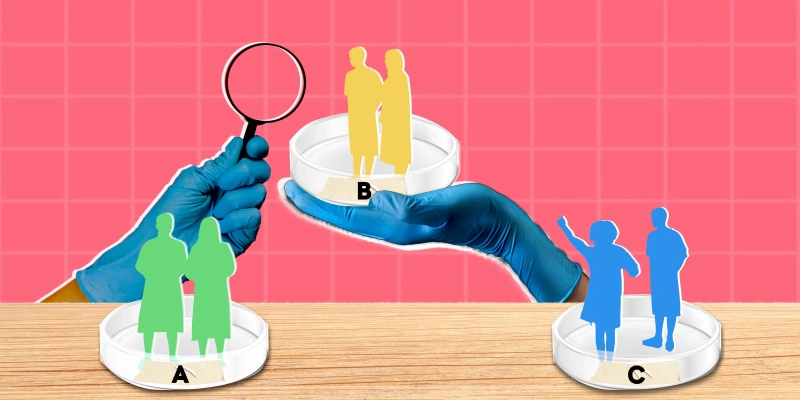

Yet, I argue that there is hope. Physicians are a unique population: self-driven, intelligent, innovative learners committed to helping people; our abilities enhanced by the parts of our lives adjacent to our doctoring - our families, our interests, our dreams. We are our greatest asset. We have to believe that unequivocally.

It is estimated that 400 physicians take their own life each year. Twenty-eight percent of residents experience a major depressive episode during training versus 7–8% of similarly aged individuals in the US (1). Approximately 24% of interns have considered taking their own life (2). But the lives and deaths of our colleagues, our friends, are more than numbers in this epidemic. Awareness is a good place to start, but action is imperative. If we empower young doctors to advocate for themselves and what is best for them and their families, you change the trajectory of medical training for generations. However, finding your voice as a trainee is complex. Instead of placing the burden on the individual, we must look critically at the culture as it stands at all levels.

I implore those in leadership positions to be mindful of the power structures you perpetuate if even by complacency. What does it say to have leadership that is promised advancement so long as they do not challenge the status quo, so long as they refrain from making waves? It starts with program directors that fulfill their role as advocates first and practice partners second - business is not just business, this is about life. Our lives.

I implore those of us currently in training to not look at the temporary nature of these years as an excuse for complacency. These are life years, worthy of intentionally living and preserving our humanity. When we graduate I ask you to not forget about the next group - you know the struggles they will encounter, the questioning of purpose, the abuse. Do not forget them. Do better for them now and when you make it out.

To those who cannot see themselves doing anything other than medicine, define your worth outside of your qualifications, scores and curriculum vitae. Explore interests that feed your soul. And hold tight to the reasons that gave your “why.”

Young doctors need to know that someone cares enough to make change, and those aspiring to be in our place need to know that there is still something worth sacrificing for. Change is uncomfortable. Physician empowerment starts with recognizing that we are our greatest asset. It starts with us, the current generation of trainees. Let us be bold in our pursuit of medical training that truly recognizes our humanity. Let our problems be relics for the next.

Dr. Chahal identifies as a humanist, mother, partner and doctor. She has a passion for justice and improving medical training.

References:

- https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/dh-ComparisonTable2003v2011.pdf

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4866499/

- https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/fullarticle/2467822