Overworked by the COVID-19 pandemic, clinicians have signaled a growing appetite for professional change and side hustle opportunities. Yet a recent poll on the Doximity network revealed that more than half are barred or restricted from one of the most popular forms of recourse — moonlighting.

The age-old practice of moonlighting, or practicing outside of a primary employment agreement, has provided many clinicians with supplemental income and the latitude to practice elsewhere. Over the past year, personal hardships prompted by the pandemic have driven nearly 40% of physicians to pursue a side hustle, according to a survey issued in the spring.

What’s more, the trend toward corporate takeover and hospital consolidation, which escalated during the pandemic, has reignited concerns over noncompete agreements that prohibit moonlighting. The American Medical Association (AMA) reported that 2020 marked the first year the percentage of physicians working in a private practice dipped below 50% since the data tracking began in 2012.

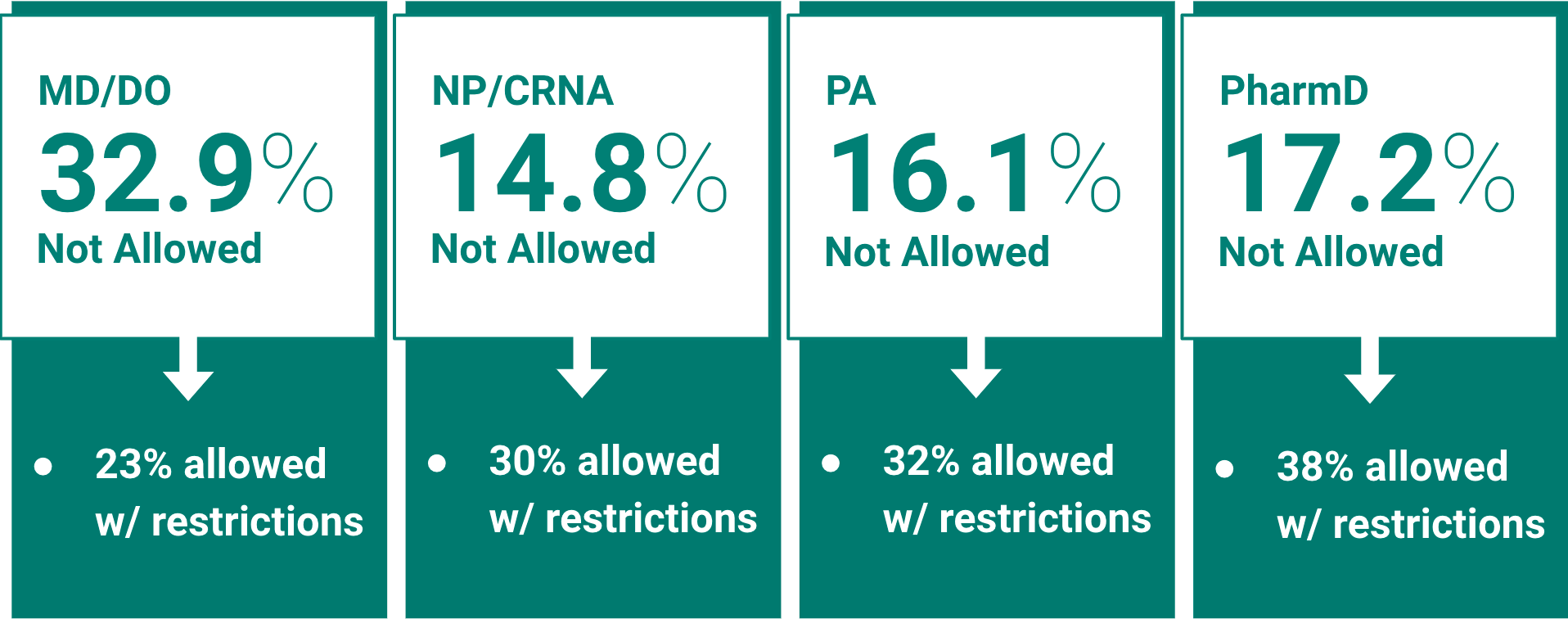

The Doximity poll, conducted in June 2021, sampled more than 4,000 health care professionals, including physicians, NPs, CRNAs, PAs, and pharmacists. Almost 30% of participants stated they are explicitly barred from moonlighting, with another 24% permitted to moonlight but with strict caveats such as a noncompete clause. Only 22% said they have free reign to moonlight, and an additional 14% said their situation is “complicated.” With the degree of approval roughly split for clinician moonlighting, the current landscape remains fractured.

Percent of clinicians explicitly not allowed to moonlight, by profession.

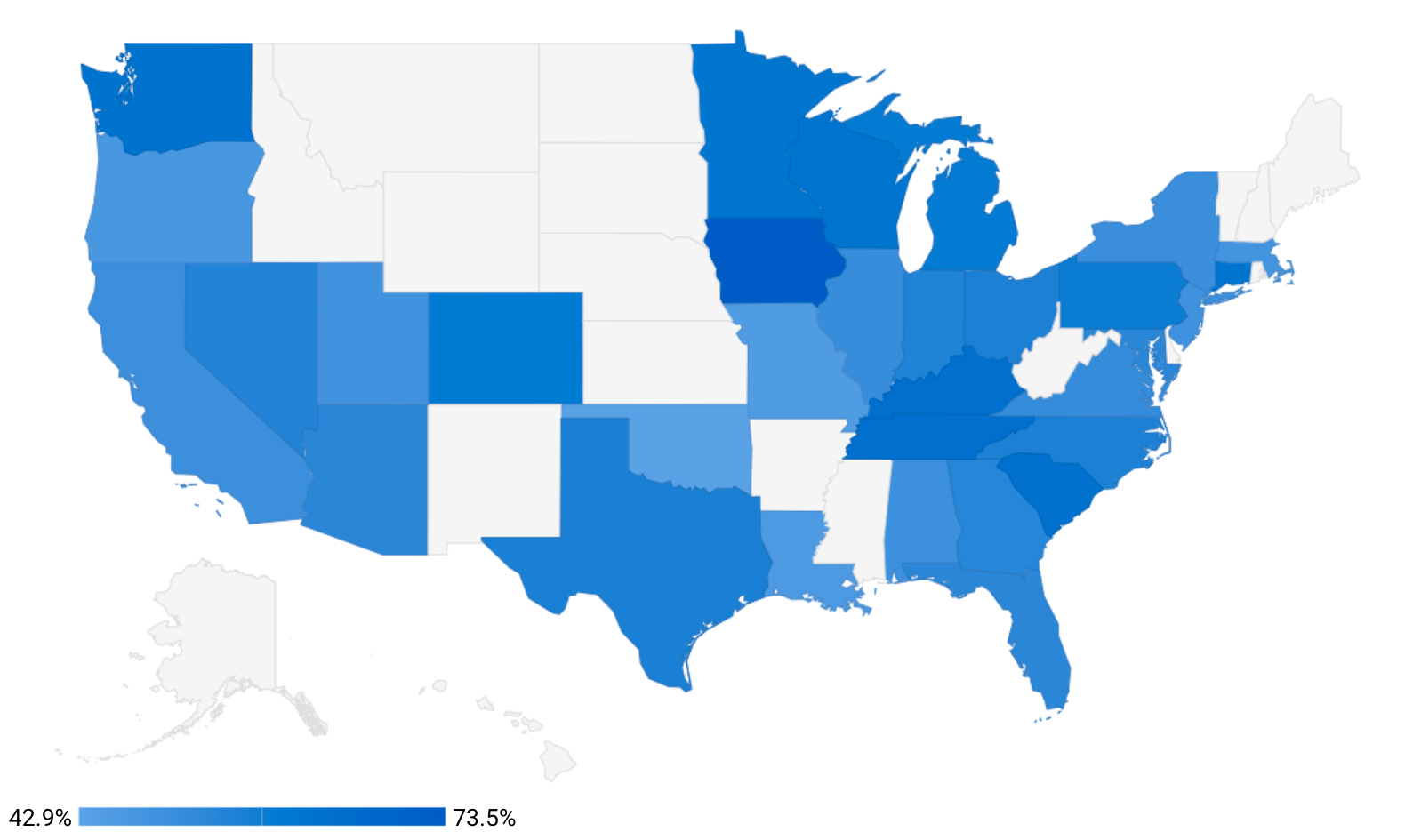

These policy variations persist across the country. In all four major U.S. regions, over half of clinicians are barred from moonlighting or face restrictions, ranging from 51% in the Northeast to 56% in the Midwest.

Across all states, Iowa is most likely to prohibit or restrict moonlighting, at 74%. The next most restrictive states are Kentucky, Tennessee, and South Carolina at 64%, followed closely by Washington (63%), Connecticut (62%), Wisconsin (62%), and Minnesota (61%). Hovering around the overall average are Texas (57%), Florida (54%), and New York (51%).

About a dozen states limit the scope of noncompete agreements for certain medical professionals. But even in states such as Oklahoma, North Dakota, and California that wholly ban noncompete agreements, many clinicians still receive requests not to moonlight. Over 50% of clinicians in California and 43% in Oklahoma face unwarranted restrictions.

Percent of clinicians barred from moonlighting or only allowed with restrictions, in the 32 U.S. states with the most poll votes.

Percent of clinicians barred from moonlighting or only allowed with restrictions, in the 32 U.S. states with the most poll votes.

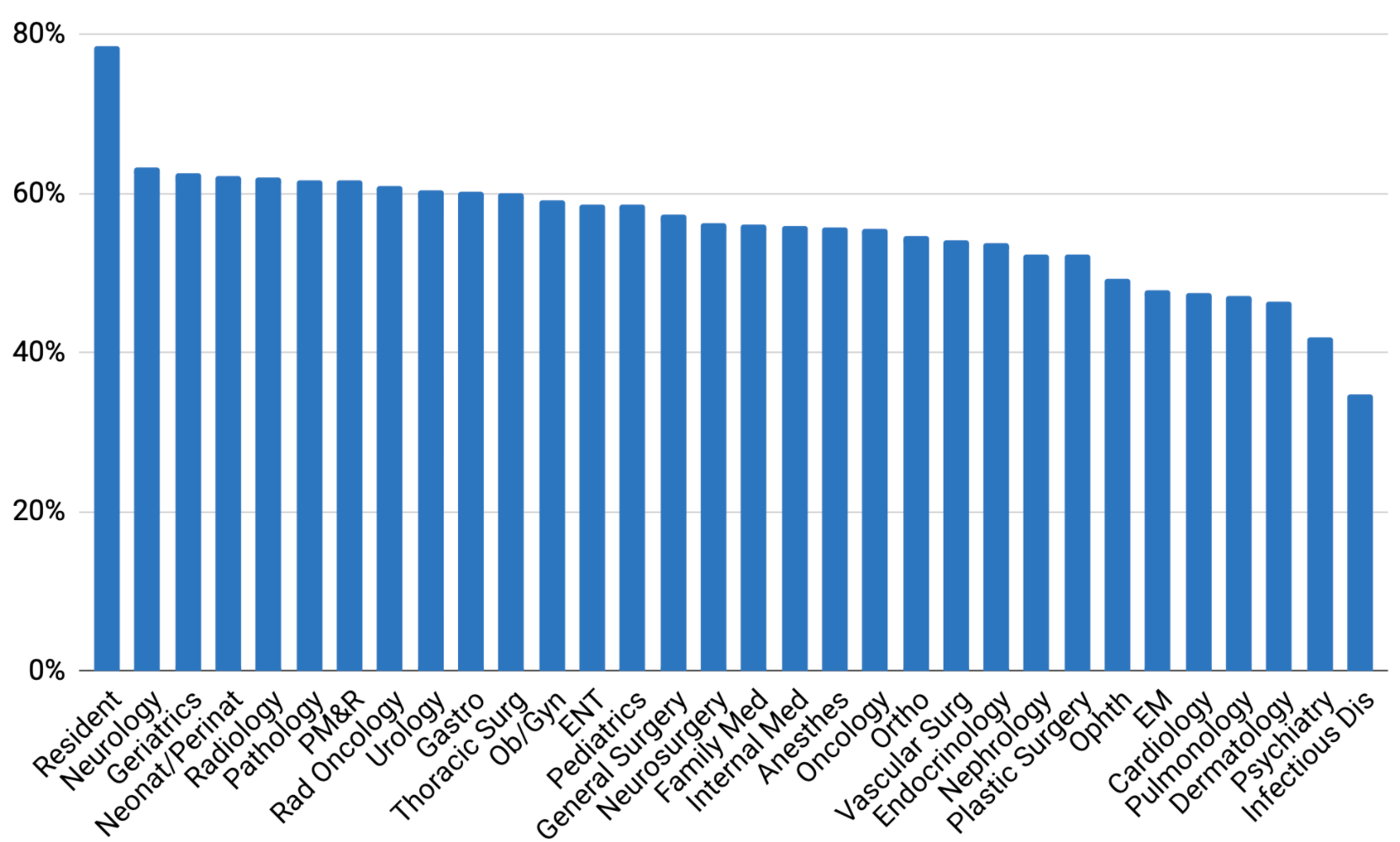

For physicians, moonlighting policies vary widely among different specialties. Neurologists and geriatrics physicians are most limited, with 63% reporting restrictions. The other most restricted specialties are neonatology (62%), radiology (62%), pathology (62%), PM&R (62%), radiation oncology (61%), urology (60%), gastroenterology (60%), and thoracic surgery (60%). Conversely, physicians least likely to face restrictions tend to be specialists, including those in infectious diseases (35%), psychiatry (42%), dermatology (46%), pulmonology (47%), and cardiology (47%).

Percent of physicians barred from moonlighting or only allowed with restrictions, by specialty.

Percent of physicians barred from moonlighting or only allowed with restrictions, by specialty.

The data also indicate that barriers to moonlighting are greatest for younger clinicians and become progressively less stringent with age. At least 64% of clinicians under age 30 face restrictions, compared with 59% for those in their 30s, 56% for those in their 40s, 51% for those in their 50s, and 46% for those age 60 and older. (Tighter restrictions for residents and trainees, who typically fall into the younger cohort, may confound this trend.)

Surpassing all other subgroups, regardless of region or specialty, are residents. Almost 80% indicated in the Doximity poll that they are not allowed, or are at least restricted from, moonlighting.

The discrepancy in moonlighting policy has vexed clinicians for years, including Matt Everett, MD, an emergency physician in Florida. At a university hospital where he once worked as an attending, moonlighting was not allowed, he said, adding: “This was economically harmful, as educators made significantly less than private practice doctors. Not to mention the loss of educating residents about private workforce issues.”

Other clinicians, including family medicine physician Charlie Rasmussen, DO, have criticized noncompete clauses and other moonlighting restrictions, urging clinicians to approach them with care. “I can’t believe anyone would sign a contract that restricts what you could do on your personal time,” he said. “Why would you ever leave that clause in a contract? Seems like a big lose-lose for physicians and patients alike.”

The AMA also recommends against agreements with unreasonable restrictions, or restrictive covenants. However, the association has previously advocated for state autonomy regarding noncompete clauses, explaining that they enable employers to provide specialized training, marketing opportunities, and access to proprietary information.

In response to rising concerns, the president’s administration on July 9 issued an executive order calling on federal regulators to “curtail the use of unfair noncompete clauses,” including in the health care market.

This directive could potentially pave the way for more clinician moonlighting and perhaps a greater sense of autonomy. Its final outcome, however, rests on the regulatory authority of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Department of Justice.

In the interim, the rise in telemedicine during the pandemic, along with expanded reimbursement, has provided clinicians with a potential workaround. Standard noncompete clauses typically prohibit clinicians from working within a several-mile radius of their hospital or clinic, without accounting for remote work. Clinicians may have access to moonlighting by using telemedicine to work from outside these defined geographic areas.

Whether or not the FTC takes up the directive, a sizable portion of the clinician workforce is pursuing additional forms of income and may continue doing so well beyond the pandemic.

How do you view the current state of noncompete clauses and moonlighting restrictions? Share your thoughts in the comment section.

Image by GoodStudio / Shutterstock