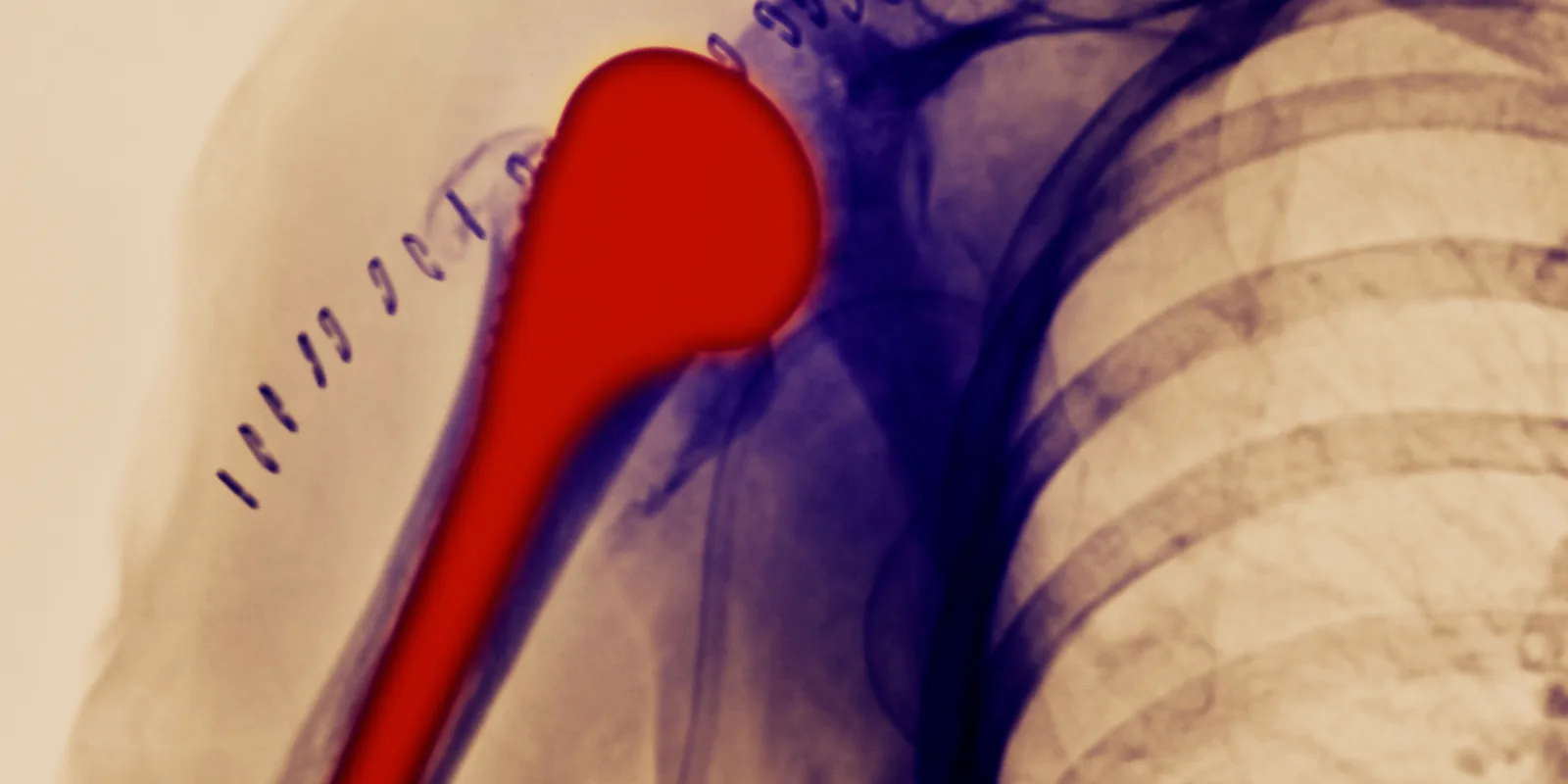

The following is a Doximity Research Review of “The Use and Adverse Effects of Oral and Intravenous Antibiotic Administration for Suspected Infection After Revision Shoulder Arthroplasty,” published in The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery.

Prosthetic joint infection is a dreaded complication of arthroplasty, associated with a significant burden of cost, morbidity, and mortality. In the shoulder, prosthetic joint infection is often caused by indolent organisms, making the diagnosis particularly challenging for surgeons. In 2018, the International Consensus assembled and, through a Delphi process, voted to establish a unified definition of prosthetic joint infection of the shoulder and a standardized method of preventing, evaluating, and managing the condition. (1–3)

Any revision arthroplasty should consider infection an important factor for possible failure. However, the role of antibiotics in cases for which the diagnosis of infection is non-definitive is unclear. There is no clear consensus on the optimal route or duration of antibiotics in the treatment of prosthetic shoulder infection; the role of antibiotics in revision cases with unexpected positive cultures is even less clear. (2) Cutibacterium acnes is a common cause of prosthetic shoulder infection and can take up to 17 days to culture. As a result, surgeons must determine an appropriate course of antibiotics based on their index of suspicion for infection, particularly in the initial postoperative period when final cultures are not yet available.

Yao et al.’s study is an important contribution to the conversation about the use of antibiotics in the treatment of prosthetic shoulder infection. In it, the authors retrospectively reviewed 175 revision arthroplasties of the shoulder, none of which had obvious signs of infection. Sixty-two patients with a high index of suspicion for infection were treated with a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line and IV antibiotics for three weeks. The remaining 113 patients, all of whom had a low index of suspicion for infection, were treated with oral antibiotics for three weeks based on criteria such as sex, radiographic, and intra-operative characteristics. In both groups, after three weeks, patients either received six weeks total of IV antibiotics followed by oral antibiotics, or antibiotics were discontinued based on culture results. Adverse events related to the antibiotic or the insertion of the PICC line were recorded.

An important finding of this study is that clinical index of suspicion is not especially accurate in predicting culture results. In those patients identified as being at high risk for infection, 21% had a negative culture result and IV antibiotics were discontinued. In those patients treated with oral antibiotics based on a low index of suspicion for infection, 27% were switched to IV antibiotics based on positive culture results. In other words, the clinical suspicion was incorrect 25% of the time and, for the patients, this meant initiation of a suboptimal antibiotic regimen.

The rate of adverse reactions to the antibiotic regimen is also of importance. This study showed that, in all, 19% of patients sustained an adverse reaction to antibiotics — 27% of patients started on IV antibiotics, and 6% of patients started on oral antibiotics. The trend was dose-dependent, with those who completed a full course of IV antibiotics followed by oral antibiotics having significantly more adverse reactions than those who had antibiotics discontinued at three weeks based on culture results. Patients who had three weeks of IV antibiotics experienced more adverse reactions than those who had three weeks of oral antibiotics. Indeed, the insertion of the PICC line itself was associated with adverse events, including venous thromboembolism (4%), catheter migration (3%), lack of access (2%), and skin irritation and erythema (9%).

Absent a reliable way to test if a patient has a prosthetic shoulder infection, the instinct is to treat everyone we think may be infected with antibiotics, at least until we can prove to ourselves that the patient is not infected. The goal is both to avoid the possibility that a patient with an infection would go untreated, and minimize the risk of infection recurrence. The problem with this approach, as demonstrated by Yao et al.’s study, is that we do a poor job of predicting who is infected. Further, administering antibiotics is not a totally benign procedure. Adverse reactions from antibiotics are a real risk, and while the risk may be worth the benefit in patients who actually have an infection, the risk is less easily justified in those who turn out not to have an infection.

This study illustrates a clear limitation in our current knowledge for diagnosing and treating prosthetic joint infection. It is not uncommon for our clinical acumen to be incorrect, and the consequences of getting the diagnosis wrong is not inconsequential. Further research that takes into account the full gamut of preoperative and intra-operative diagnostic information is needed to refine the diagnosis of prosthetic shoulder infection. More research also needs to be done to study the treatment of prosthetic joint infection and evaluate whether the side effects of PICC line insertion and strong IV antibiotics are merited by an increased infection eradication rate — and in which patients. With this study, Yao et al. does an excellent job of illustrating the current state of the field in treating prosthetic shoulder infections and highlighting the areas that are in need of more research.

References

1. Garrigues GE, Zmistowski B, Cooper AM, Green A, Group IS. Proceedings from the 2018 International Consensus Meeting on Orthopedic Infections: evaluation of periprosthetic shoulder infection. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2019;28(6S):S32-S66. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2019.04.034.

2. Garrigues GE, Zmistowski B, Cooper AM, et al. Proceedings from the 2018 International Consensus Meeting on Orthopedic Infections: management of periprosthetic shoulder infection. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2019;28:S67-S99. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2019.04.015.

3. Garrigues GE, Zmistowski B, Cooper AM, et al. Proceedings from the 2018 International Consensus Meeting on Orthopedic Infections: the definition of periprosthetic shoulder infection. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2019. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2019.04.034.

Lisa G. M. Friedman graduated from Case Western Reserve University with a medical degree and a master's degree in bioethics. She is currently the orthopaedic trauma research fellow at Geisinger Medical Center. Her interests include shoulder and trauma surgery, and she enjoys creative writing and playing sports in her free time. Dr. Friedman can be found on Twitter, @Shoulder2LeanOn. She is a 2020–2021 Doximity Research Review Fellow.