“Try to approximate the periosteum,” the first year ENT resident, masked and with his gloved hands in the air, told me, peering over my shoulder at the face of the barely conscious young man lying on the gurney. “Use 3-chromic on the sub-Q and 4-0 nylon on the skin.” He then walked out of the treatment room to the room next door where he had been re-attaching a partially severed ear of a man who was not yet in the habit of wearing a seatbelt while driving (it was 1970), and whose head and windshield had met rather forcibly earlier that evening.

This was my first night on call as a pediatric intern at the Los Angeles County-University of Southern California Medical Center, AKA “The County.” Just a few weeks prior, had I been on duty at my medical school hospital emergency room, two of the 7th year plastic surgery fellows would have been summoned to tend to that man’s ear and my patient’s face.

Now, however, there I sat, as a month on Ear, Nose, and Throat was a mandatory rotation in the straight Pediatric Internship at The County (to, I imagine, prepare us for all the sore throats, possible nasal foreign body extractions, and otitis to come in our careers), and, at The County, in those days, all head and neck trauma went to ENT.

He was a “Red Blanket,” my young patient, who, after an ER assessment, having been judged sufficiently stable for trauma repair, was wheeled through the hospital halls with a crimson blanket draped over the foot of his gurney. The blanket signaled an emergency, cleared a path to the nearest elevator, waiting passengers stepped aside, and, with the gurney on board, the elevator lifted the patient non-stop from the first floor to the 11th floor ENT department and me, his not-much-older young doctor.

He had been in a gang fight. No guns aimed from moving cars back then, but a rival wielding a lead pipe, very up close and personal, that had caused multiple chest contusions, a linear skull fracture and scalp laceration, and, a transverse craniofacial fracture that had left my patient’s nose hanging down over his mouth: a “Le Fort III” fracture, as it was known, I later learned, that had loosened his maxilla from its facial perch.

I glanced at the nurse who nodded and gestured down at the suture material and instrument kit she had placed near me on a tray as the resident had been giving me his instructions. I gloved, leaned over my patient, liberally injected local anesthetic, and began to sew. It was two in the morning. I sewed until nearly dawn completing an “as best as I could plastic repair” to his face and closure of the scalp laceration. I escorted him to Radiology and back to the Unit to await the oral surgeons, and to begin my morning rounds.

I saw him every day for the remainder of my rotation. His jaw was wired shut and the surgeons had extracted two teeth so he could eat through a straw. He could not speak.

I rotated off that service, and several weeks later, while on a break in the hospital cafeteria, I looked up when someone tapped my shoulder, and there he was.

“How do I look, Dr. Sandler?” he asked with the hypernasal resonance of someone whose palate was not quite healed. “You look great,” I said with some hesitation. “How do you feel?” “I’m good,” he replied… feeling stronger every day…”

We exchanged a few more pleasantries, shook hands, and parted. I never saw him again.

I cannot truly know how his experience, the trauma, and treatment affected him, nor do I know how he may have adjusted, during his life, to the events and the scar, that I had left him, that crossed his face. I can hope that his seeming comfort during our brief “post-op” encounter would have remained.

I had survived this first County “initiation under fire” and I made it through the subsequent training “traumas” that can beset all public hospital house staff. At The County, we saw nearly “everything,” we worked above and below our station, we learned, we taught, and, with great care, we felt stronger every day.

Memories of those experiences can be like scars. I can “push” on those memories and recall the events no longer with the anxieties of my then front-line training. Scars don’t hurt.

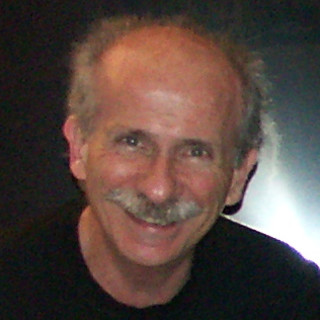

Alan Sandler is a Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist with “Triple Boards” having returned to residency and fellowship training in General and Child Psychiatry following completion of Pediatric training, a stint as an Air Force pediatrician, an MPH in Maternal and Child Health, and several years on the pediatric faculty at LA County USC Medical Center. For the bulk of his “second” career, he has maintained a mixed public (Community Mental Health Center)/private office (Fee for Service) child and adolescent practice, and serve on the Voluntary Clinical Psychiatric faculty at UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute.