We’d moved to Rocky Creek for my new job at the medical school. We’d survived or endured or enjoyed my six years of training in Boston and, frankly, I’d hoped for a more prestigious posting. But state medical schools have their own threadbare, populist cachet. Carol, three months pregnant, had crossed the waters (Long Island Sound, to be exact) to hunt for our first house. On weekends, I’d come to examine the haul.

We were returning not to Manhattan’s familiar haunts, but to a rustic outpost two hours away by diesel and electric trains. When I asked natives how often they visited the City, their blank looks said: “And why would I do that?” At 48, I was overdue for adulthood — a real job after decades of occupational free fall capped by residency. The novelty was unsettling and sublime.

Like a boy clomping around in his father’s shoes, I was a newbie at homeownership. Our toy-like furnace fit in a closet, so unlike the behemoth that heated my childhood building. Our precious rhododendron bushes, the crown jewel of our property, died. I had debated with my wife: do we have to water them? You do. We didn’t. They died. Mental note: rhododendron bushes do not “just grow” like shrubs in Central Park.

Remembering that time, I think of light. The sun seemed to pry open every cranny of our new abode and made every tree in our hamlet shimmer and flash. Color leached from the landscape as if blasted by a thermonuclear device. A vast silence accompanied the glare; the sun seemed to absorb any sound that tried to escape its dazzle.

But maybe that’s giving the sun too much credit. Memory’s the atomic fuel, and all that light emanates from a belly where our second daughter bobbed in amniotic bliss. Every morning, I brought Carol a cup of decaffeinated coffee that she despised. We called it “dog water.” Surges of emotion buffeted our isolation in our quasi-suburb, at once luxuriant and desolate.

That job, my first real job as a doctor, was the third adult act of my life, the first two being the conception of our daughters (though some boyishness went into that business). As a new man in the department, my comportment needed to be exemplary. All eyes were on the greenhorn: are his diagnoses spot on? … He looks mighty shaky ... Does he brew his share of the communal coffee that spices the office air with intimations of caffeine? Eons would undoubtedly pass before I’d be considered an old hand.

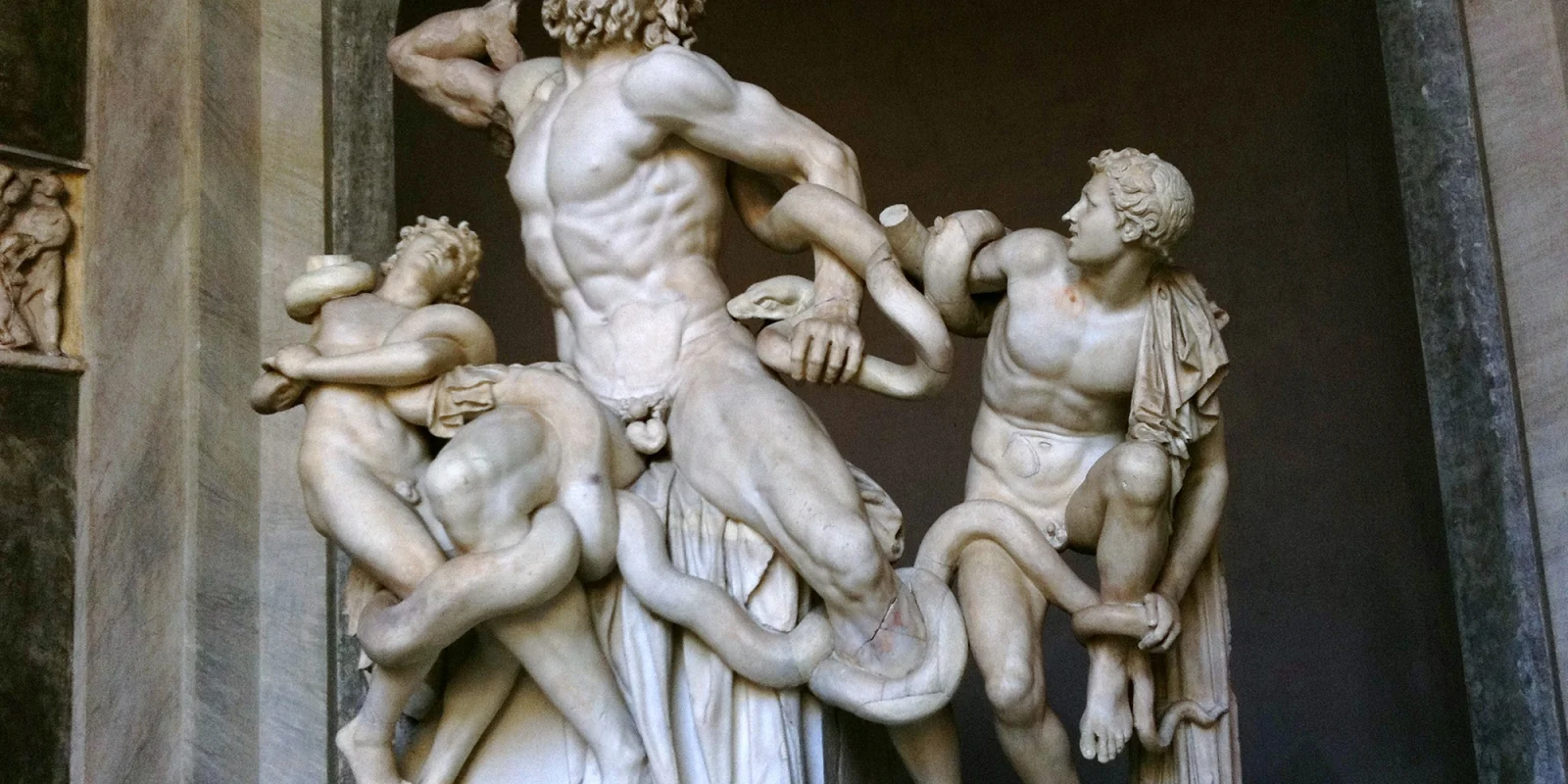

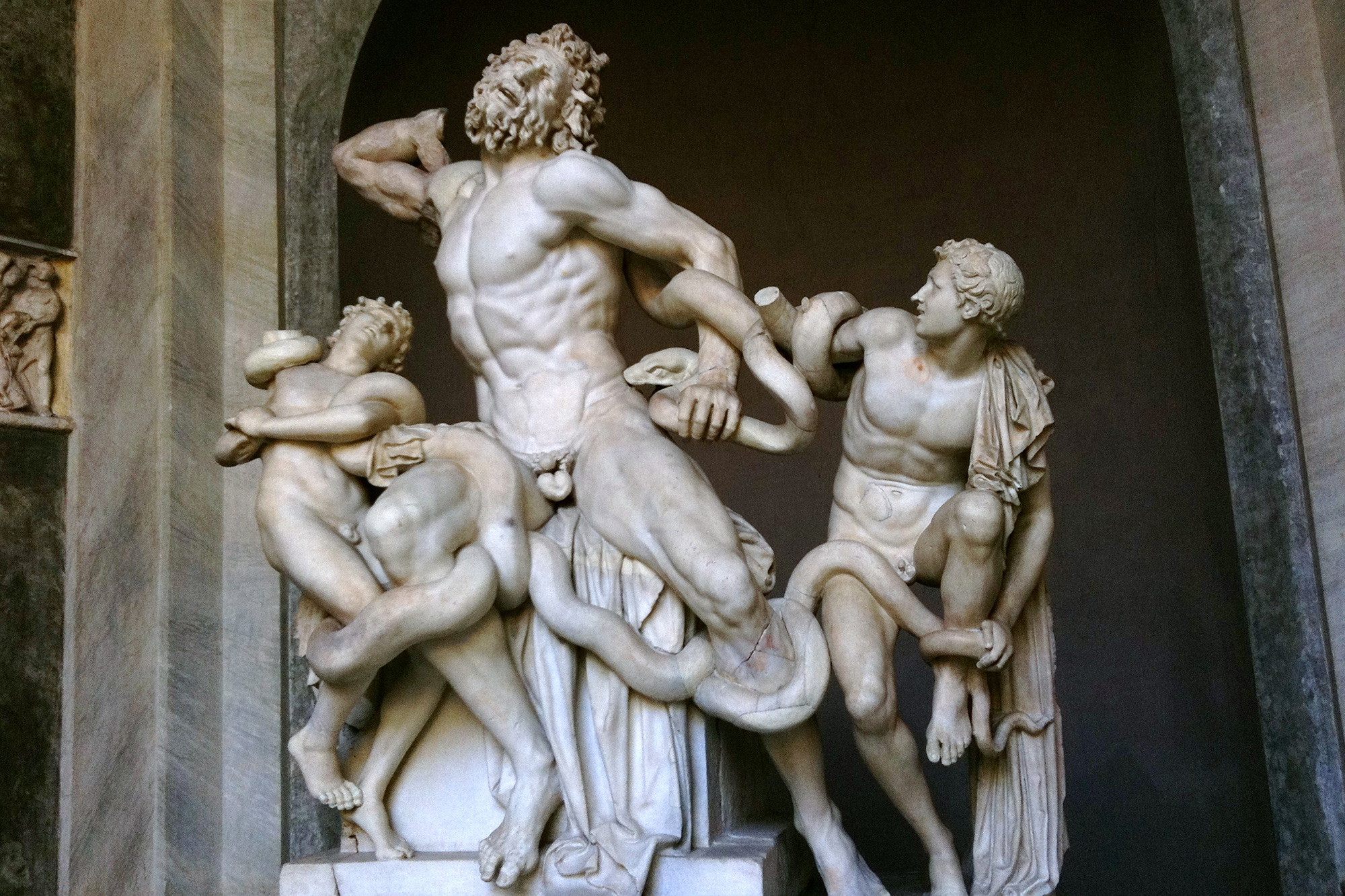

Shortly after my arrival, I was party to some peculiar incidents. To appreciate the first, one requires a detour into, of all things, art history: It is a major work, called "one of the finest examples of the Hellenistic baroque.” When it was unearthed in Rome in 1506, no less an art-historical figure than Michelangelo rushed to inspect it. It is the statue best known as “Laocoön and His Sons.” It attempts to solve an ancient conundrum: how to beautify the depiction of extreme suffering.

Who was Laocoön? The wily Greeks had presented the Trojans with a wooden horse stuffed with Greek warriors. As the Trojans prepared to haul this mysterious gift into Troy, Laocoön, a priest and no fool, shouted his famous caveat: “Watch out boys! Whatever this thing is, I fear even the munificence of the Greeks.” The goddess Athena, an enemy of the Trojans and eager for the cunning Greek gambit to succeed (and her patience sorely tried by Laocoön’s hysteria), sent two magnificent sea serpents, red eyes gleaming, to entwine Laocoön and his sons — to polish them off. And thus, fictitious though they are, three more doomed white males were introduced into the Western canon.

Back in Rocky Creek, it was late Friday afternoon. We were all tired, anticipating the comforts of home; maybe some of us had gotten a little sloppy. My fellow attendings, in fact, had already deserted our basement pathology suite, leaving me alone with my so-called thoughts and a skeleton crew of residents. As a recent hire, I felt obligated to demonstrate my work ethic by being the last to leave. Poking my head out the door, I noted that all of the other offices were dark at last. Even the meager cubicles for the residents had been abandoned. There was one last thing to check: the grossing room. And, indeed, muffled sounds of distress seemed to be issuing from that quarter as I began my patrol down that dusty corridor. What did I see when I emerged from the dark into the searing light of the grossing room? It confounds the imagination. Three residents, two short and one tall, were bound by a long section of colon that twisted around each of them before disappearing down into a sink. Their faces were contorted with terror; they were flinging their limbs every which way, desperate to master the slippery, coiling beast of a bowel. All I could hear were their cries of alarm and, strangely, grinding noises that sounded an awful lot like a garbage disposal masticating a particularly tough meal. As I took a closer look at their configuration, my face acquired its own horrifying cast. It was indeed a garbage disposal that I heard, and it was grinding away at one end of the colon. The residents themselves, aware that it was bad form to forfeit a specimen to plumbing (and knowing how soundly their heads would be whacked if they did) were struggling to retrieve it from the all-consuming maw. Absorbed as they were in their combat, they hadn’t noticed me. I wondered if, qua attending, I was professionally (if not ethically) obliged to try to liberate them and the abused organ from the rotating blades … but I would have preferred to play no part in their catastrophe, which was looking irreparable anyway. Thinking quickly (but very carefully!), I made a decision. I swiveled unobtrusively on my heel and headed back whence I came to my tranquil office.

Thus does life imitate art. Why was Athena nosing around my obscure pathology department, so far from her native city and customary concerns? Who can say? But I’d weathered my first crisis as a new attending … I fear now I did not come off handsomely at all.

After teaching English for over a decade, Dr. Weissmann swerved and went to medical school. He is currently a hematopathologist in New Jersey.