As a non-psychiatrist, I really cannot tell you the difference between the diagnoses of hypochondriasis, malingering, Munchausen/Munchausen by proxy, or the disorders of conversion and somatization. I can, however, tell you that the third leading cause of patient mortality in this country is medical error, and, as an allergy/immunology specialist, I know that even the most common, immune-mediated disorders, such as rhinitis, asthma, and food allergies are not commonly recognized by general practitioners and specialists, leaving children and adults under-diagnosed and untreated.

As a non-psychiatrist, I really cannot tell you the difference between the diagnoses of hypochondriasis, malingering, Munchausen/Munchausen by proxy, or the disorders of conversion and somatization. I can, however, tell you that the third leading cause of patient mortality in this country is medical error, and, as an allergy/immunology specialist, I know that even the most common, immune-mediated disorders, such as rhinitis, asthma, and food allergies are not commonly recognized by general practitioners and specialists, leaving children and adults under-diagnosed and untreated.

Reasons for this stem from the lack of training received during medical school and postgraduate residency training: allergy/immunology is barely featured in the undergraduate medical school curriculum, which is when the foundation of most clinicians' working knowledge is formed. Further, the clinical specialty has a minimal presence in most hospitals and medical centers, which often translates to suboptimal care and poor outcomes of pediatric and adult patients — in the ED, in the operating theaters, in the ICUs, and on the floors.

Recently, one of my patients, who had a pain syndrome from tumors wrapping around her spine (as well as a long list of drug allergies and intolerances), landed in the ED of an Ivy League medical center. The physician assistant could not call for an allergy/immunology consult because there was no in-house allergy/immunology department. In the same week, another young adult, female patient with cervical spine instability, ulcerative colitis, and a history of migraines presented to a community hospital with symptoms worrisome for anaphylaxis — but because the patient did not have hives (acute inflammation of the skin), the medical resident asked me if I thought this patient had Munchausen or conversion disorder. The conversation began with, “She has so many diagnoses and is taking so many medications ….” I informed the medical resident that upwards of 10% of anaphylaxis cases will not have obvious skin symptoms.

Asthma is one of the top three reasons for pediatric hospital admissions in the United States. In Harlem, from 110th St. to 168th St., from the Hudson River to the East River, home to over 116,000 residents, not one allergy/immunology practice exists. Only the clinics attached to two medical centers, which are on the outskirts of the community, attempt to provide a home for this chronic medical condition, in supervised residents’ clinics. Rhinitis, often considered a nuisance of an ailment, affects nearly half of urban dwellers and is one of the most common reasons for absenteeism from school and work.

Food allergies, occupational allergies, and eczema are also on the rise. Indeed, research indicates that in any given room containing 100 people, at least two have been treated for anaphylaxis — and many more carry epinephrine auto-injectors, given the risk of this potentially life-threatening, hypersensitivity condition.

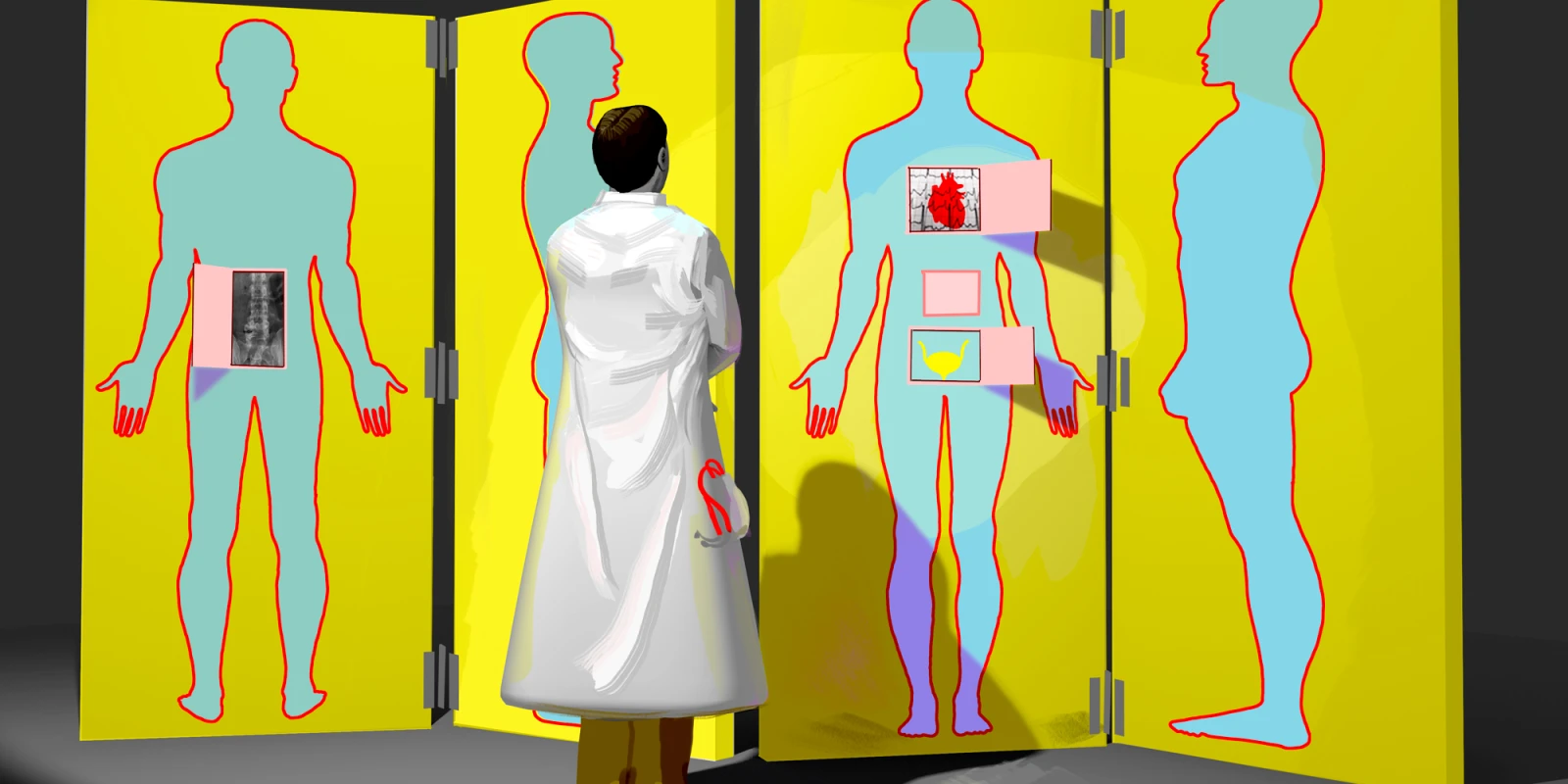

A report from the Royal College of Physicians states that allergic diseases are so complex, involving multiple organ systems, that patients are often referred to “a succession of different specialists.” After inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract and skin, inflammation of the brain, the spinal cord, and peripheral nerves is a commonly reported symptom of aberrant mast cell activation. So, it is not surprising that patients with the newly-described chronic hypersensitivity disorder, mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS), or syndromes that mimic or can travel with MCAS, such as Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS) or Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS), have neuropsychiatric symptoms that come and go, and often receive one of the above-mentioned psychiatric diagnoses.

According to an article written in 1984, “It is known that the majority of antidepressants and minor tranquilizers are prescribed by nonpsychiatrists.” In a more recent 2017 New York Times article, the author noted that nonpsychiatrists — even if they are medical doctors in other fields like cardiology or gastroenterology — “are often ill-equipped to recognize and treat emotional symptoms related to a physical ailment.” And, by the same token, “psychiatrists may not consider the possibility that a patient with symptoms like palpitations, fatigue or dizziness really has a physical ailment.” There are countless examples of patients who are given psychiatric diagnoses before their underlying organic disorder is uncovered. Granted, physical ailments do cause neuropsychiatric conditions and some of these medications have indications for non-psychiatric disorders. However, there seem to be few reports on the follow-up care of pediatric and adult patients, who were previously given a functional disorder diagnosis – such as conversion disorder, hypochondriasis, malingering, Munchausen, or somatization – and then found to have an organic ailment. The fate of these patients has already been captured by Francis Peabody, one of the godfathers of modern medicine, in his 1927 classic article, “The Care of the Patient.” He wrote, “[T]hese patients [with nothing wrong with them] constitute a large group, and their fees go a long way toward spreading butter on the physician's bread. Medically speaking, they are not serious cases as regards prospective death, but they are often extremely serious as regards prospective life. Their symptoms will rarely prove fatal, but their lives will be long and miserable, and they may end by nearly exhausting their families and friends. Death is not the worst thing in the world.”

Missteps and misunderstandings, even by well-seasoned medical professionals, are human, but medical gaslighting is not. Medical professionals must take a step back and recognize that the interpretation of test results is only as good as the practitioner glancing at the numbers. Moreover, normal test results in patients with chronic pain, unexplained sensitivities to the world, or fatigue should provoke more investigation, rather than a weak handoff to a mental health provider. One potential remedy to avoid these misdiagnoses and medical misdemeanors may be to rebuild the patient-practitioner partnership: the medical home. We should be empowering the patient to take charge of their health care, and we should be reminding the practitioner to be a mindful partner in health, rather than a patriarchal purveyor of prescriptions and procedures.

Dr. Anne Maitland is an allergist/immunology specialist. She is an Assistant Professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and is the medical director of Comprehensive Allergy & Asthma Care, in Tarrytown, NY. She earned an MD and PhD from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and has been in practice for 20 years. She serves on the AAAAI Committee for mast cell-mediated disorders and the committee for the unmet need.

Illustration by Jennifer Bogartz