It was just before Christmas of my third year of residency when I received the call from my mother telling me the results of her biopsy. She had told her pathologist that I was a doctor, and immediately her doctor wrote down the exact size, type, and location of the lesion so that my mother could relay the information to me. I knew he did not give this much detail to other patients when disclosing biopsy results, and I appreciated the details.

I will never forget my mother’s voice as she said, “Infiltrating ductal car, I can’t read that word, c-a-r-c-i-n.” I interrupted her before she finished spelling out the word. I knew what we were dealing with and all the implications of the word. The innocence in her voice immediately thrusted me into a spiral of uncertainty. I grasped for control by interrupting her. At the time, I did not realize what my response indicated about me.

Christmas day seemed like just another day that year. The highlights of the season were not feasting and presents, but rather mastectomy and recovery. My mom had to pack up the small Christmas tree (a gift from her wonderful friends) and take it back to her two bedroom rental home. Christmas day and the days to follow were my first experience of being “the caregiver.” They opened my eyes to the cost of my medical training thus far.

Over the past 3½ years, I spent my days in the hospital or clinic. I spent my time moving from hospital room to hospital room rounding on patients. I reconciled the discharge medication list and wrote prescriptions for pain medications. I spent multiple morning hours looking over nursing charts for the 24-hour totals on drainage bulbs.

In the past two weeks, I spent my time giving baths to my mom, treating the nausea caused by the narcotics, and emptying her drainage bulbs to record the totals for our next doctor’s appointment.

It was not that I resented the new role. The truth was that I loved the feel of my mother’s thick blonde hair as I stroked her head, and appreciated the chance to run my fingers through her hair before it all fell out. I was grateful to live close enough to spend a few weeks of a clinical break helping her recover from the bilateral mastectomy and reconstruction.

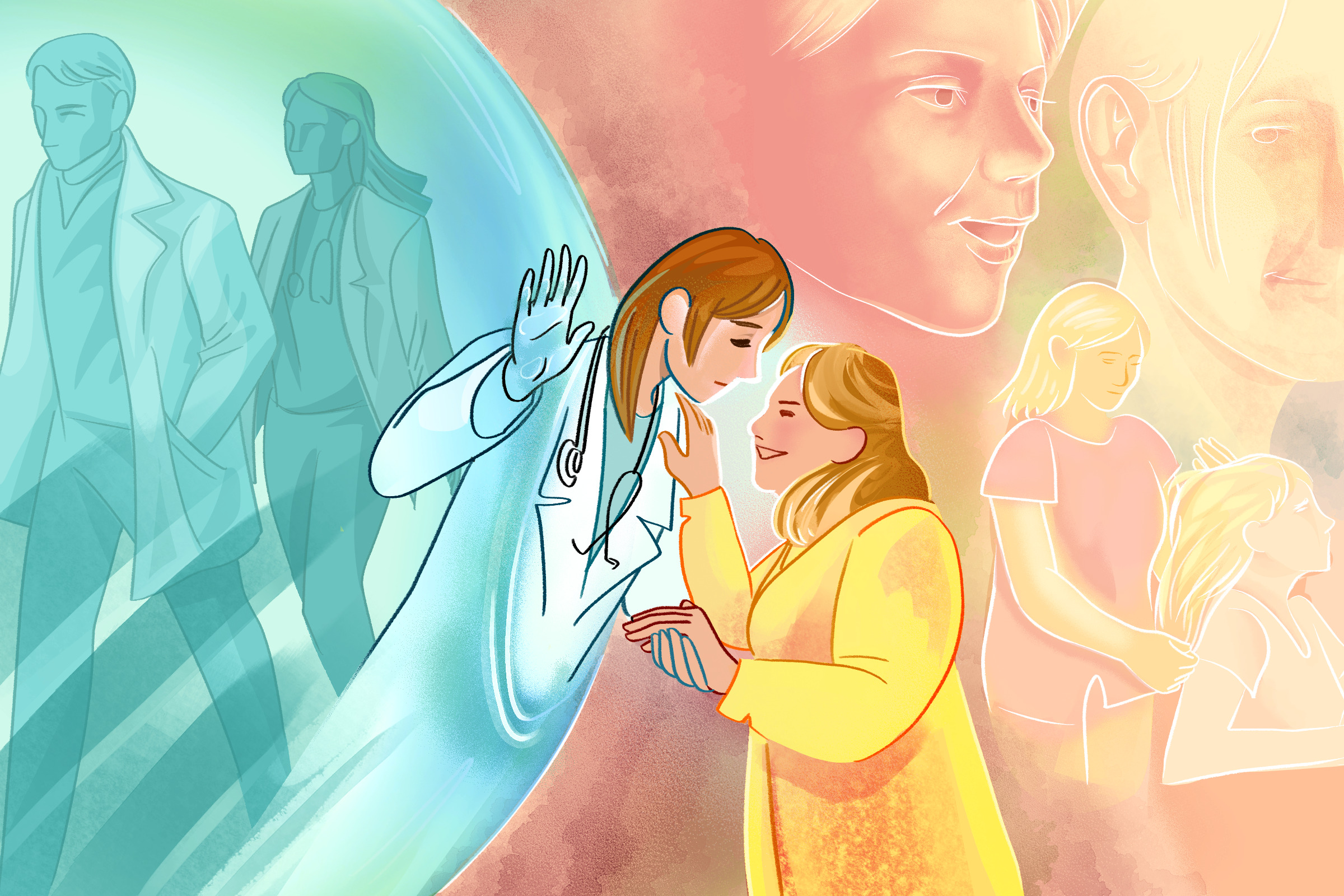

The stress of being the caregiver instead of the doctor was a “first” that I never anticipated would affect me so deeply. The strong, knowledgeable, controlled doctor image that I often found myself portraying did not really have a role in this season of my life. My mother’s small, warm, loving rental house was a stark contrast to the cold, clean, intimidating, and life-changing hallways of the hospital.

It was helpful that I could translate for my mother as she spoke with her doctors. I noticed a difference between the gaze my mother received from her doctors and the gaze I was privileged to receive from the same doctors. My perception of their glances was a, “You know what I mean” or “Don’t you agree?” I am ashamed to admit that at first I returned those looks with my own glances of:

You explained that very well, doctor.

I will clarify with her later.

I know it is more complex; say no more.

Then, as I became more detached from the hospital and spent more time in my mother’s loving and warm presence, I began to let my brow furrow in worry and concern. I began to let myself give an authentic glance to the doctors, as if to say, “Please doctor, save my mom. Don’t let her feel any more pain.” And “Please give her something to get rid of the nausea because I can’t see her vomiting any longer.”

As I reflect on this experience, I can now see that I was learning how hardened my heart had become in the years of my medical training. It was a necessary transition that I had to make in order to endure the extremely emotional moments that I was experiencing at the time. I had immersed myself in medical literature, test taking, clinical diagnosis, and treatment so much that the soft part of my soul had no room to thrive.

I am not judging the process of my medical training, but only defining it for myself, as a means of honoring it. My eight years of medical training had grown my intellectual and clinical self into the doctor that I had wanted to become. At the same time, my performance-driven, egocentric self had taken over the human part of my soul.

Over the past 15 years, my mother has recovered and is now cancer-free. I have moved into a season of medical practice where the emotional experiences are less trauma and more shared experience. I am also in a place in my own life where I am learning to hold both parts of my soul in balance. Medicine is largely an intellectual endeavor, and without our intellects, the progress in medicine would not thrive. However, medicine is also a human endeavor. The soft parts of our souls are at risk of being forgotten in this fact-driven, performance-based career path.

Now, when I visit my mom, I can more quickly move into the human part of my soul. She has this habit of giving me medical advice. Recently, she and I were discussing the benefits of different foods on our health. She was going on and on about how these certain herbs and supplements are supposed to be the “superfoods” of the future. In the years past, I would have given her a summary of an article describing the benefits of the mediterranean diet as opposed to relying on the most recent fad “herb” or “supplement.” Instead, I smile, gaze into her eyes, and appreciate hearing her voice.

Katrena Lacey is an Internist/Pediatrician practicing in a small community outside of Omaha, Nebraska.

Illustration by April Brust