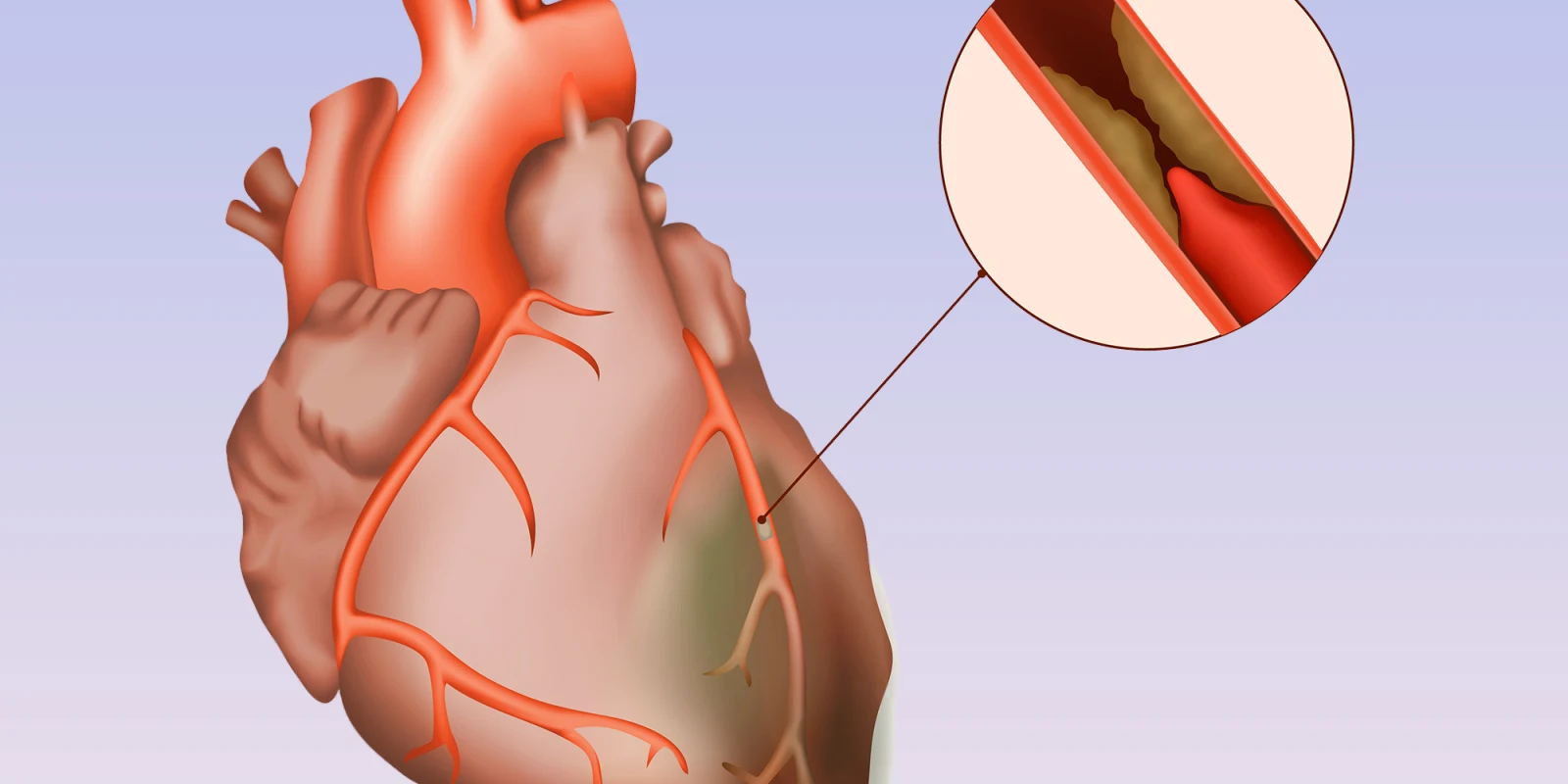

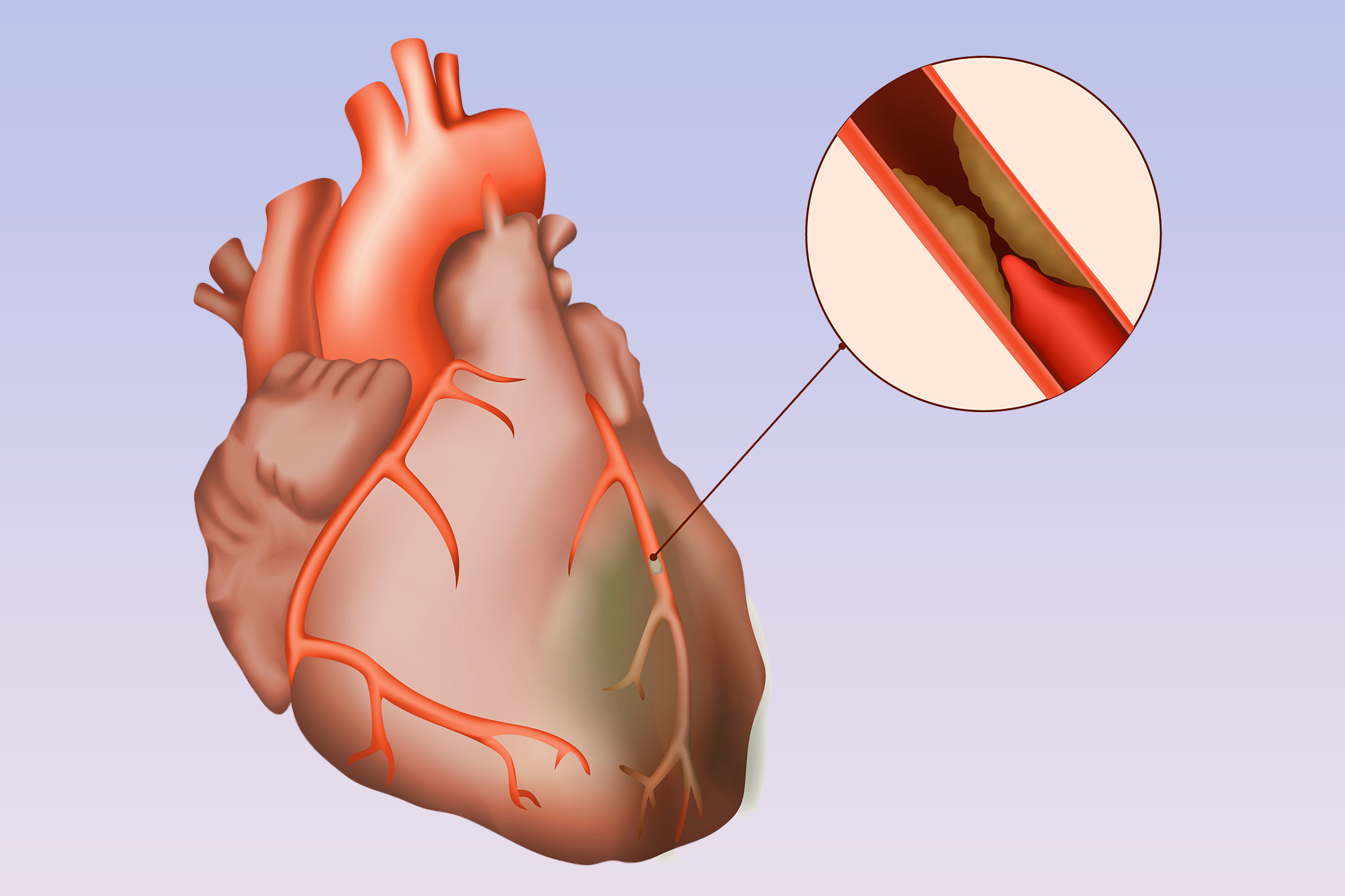

At this week’s American Heart Association (AHA) Scientific Sessions, the ISCHEMIA Trial comparing revascularization with either coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and optimal medical therapy to optimal medical therapy alone without revascularization was presented. Patients had stable ischemic heart disease, not acute syndromes like heart attacks or progressive chest pain, at least moderate ischemia on stress testing, and could not have left main disease. The headlines on presentation touted “revascularization no better than medications” for stable ischemic heart disease, but the truth is oftentimes much murkier. Here’s another take.

The trial was difficult to enroll, with an anticipated 8,000 patients that ended up being 5,100. Why? Partly because our own entrenched biases channeled most patients into revascularization, but also because there were 28 exclusion criteria including many high-risk comorbidities such as reduced ejection fraction, prior recent PCI or stroke, and renal disease, among others. This results in lower-risk patients entering the trial, and an under-powering for the predicted event rates, such that non-inferiority is almost a foregone conclusion. With lower-risk comes lower event rates, and thus about two years ago the trial had to expand the primary endpoint to add the softer variable of hospitalization for unstable angina, heart failure, or sudden cardiac arrest. In other words, the writing was on the wall for some time that this trial would be negative as initially devised, and not necessarily because the theory of mechanically targeting ischemia is wrong.

Now for the data. True, over the five years, there was no statistical difference between strategies in the overall population. Ultimately, 80% of those assigned to revascularization actually received it and about 25% of those assigned to medical therapy crossed over to revascularization, similar to the previous COURAGE trial. Diving deeper, however, there was an early excess risk of 1.9% for the primary endpoint in those who underwent revascularization, an expected finding when you subject patients to invasive testing and treatment. This risk flipped and by 4–5 years those who had undergone revascularization trended to fewer events by a similar margin of 2.2% (RRR 7%, p = 0.34). The same trend was seen in the new secondary endpoint of cardiovascular death and myocardial infarction (MI), which previously was the primary endpoint, with a final RRR of 10% (p=0.21). When you look only at spontaneous MI during this time, ignoring the upfront peri-procedural events which in virtually all studies has been found to be inconsequential, there was a statistical reduction in spontaneous MI over time with revascularization (RRR 33%, p<0.01), and this benefit continued to grow.

This begs the question, are peri-procedural events as dangerous as spontaneous events down the line, and which are more important to us as physicians and patients? And what would happen if you continue to follow these patients? Would the majority crossover such that non-inferiority remains, or would the curves continue to diverge favoring revascularization? For one thing, most peri-procedural events do not affect ventricular function, occur in the safety of the initial hospitalization, and for both PCI and CABG, are no longer tracked routinely for these reasons. Indeed, PCI is moving to the outpatient setting soon and no one appears to be worried about peri-procedural MI. On the other hand, spontaneous MI years later, when the patient is home and presumably doing well, are by definition clinically important.

An analogy could be made to the recent EXCEL trial. The trial showed non-inferiority for PCI as opposed to CABG in left main disease, but there was again an early risk of CABG and then improved outcomes in that arm over time relative to PCI. Presented as non-inferiority by trial’s end, a victory for PCI, much debate ensued that it actually may hint at a benefit to CABG that may emerge over time. If one were to believe this addendum to EXCEL, one must also believe that revascularization may show a benefit over time as the dust settles on ISCHEMIA and more events accrue. Indeed, CABG may be driving the majority of late benefit in both of these trials.

Taken together, I believe a more accurate albeit nuanced headline would be that revascularization to treat moderate or severe ischemia does indeed benefit patients by reducing spontaneous MI due to progression of disease. This in actuality supports our long-held beliefs that ischemic burden predicts future events, but that the early procedural risk inherent to the tools we have today may outweigh the benefit in some patients, at least at five years. Our focus should now be on finding ways to reduce ischemia as completely as possible, with both medications and revascularization, while making upfront risk of revascularization more palatable, and determining which patients have the most upside to an invasive strategy, perhaps those with the largest ischemic burden, those with left ventricular dysfunction, or those who are symptomatic.

Sometimes the true benefit takes time to see. What data do we have that five years of follow-up is all that is necessary? How do we handle crossover? What do we tell our clinicians and patients? Fortunately, ISCHEMIA will be following patients for an additional five years. Perhaps we should continue to dive into subgroups, contemplate devising other trials in higher risk populations, continue to perfect our technology, and yes, our medical therapy too, consider removing peri-procedural events that are not clinically significant or even tracked routinely, and reserve final judgment. We owe it to our patients, our physicians and society to get this one right.

Dr. Srihari S. Naidu MD, FACC, FAHA, FSCAI is Director of the Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory and Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Center at Westchester Medical Center and Professor of Medicine at New York Medical College. He is a Past Trustee of the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI), Trustee Emeritus of Brown University, and President-Elect of the New York Chapter of the American College of Cardiology (ACC).