I entered the hospital, my volunteer badge hanging off my shirt and a cloth mask covering my face. I walked through the main entrance and was immediately greeted. “Please step to Lane 1.” I stepped up to a serious looking employee who politely asked, “Have you felt sick or had any symptoms in the last 30 days?” I replied no. I felt like I had stepped into another dimension — I hadn’t been to the hospital since the coronavirus precautions started. I was functioning as a No One Dies Alone volunteer, and I was here to sit bedside with a patient and provide compassionate companionship during her dying process.

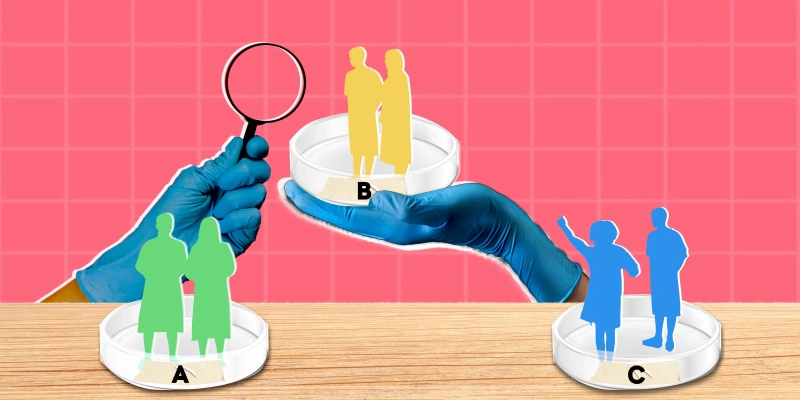

Before entering the hospital that day, I hadn’t reflected on how a pandemic could have a multitude of different effects — including changing palliative care, dying experiences, and caregiver grief — and in turn amplify the already excruciating pain of death. As a health care community, we count the death tolls, number infected, number treated, and number saved. But what we have not quantified is the emotional, spiritual, physical, and psychological toll on a patient’s loved ones and family members. This is important to both patients with and without COVID-19.

I made my way up to the patient’s room. I walked in and introduced myself, letting her know I would be sitting with her for a while. We were sitting peacefully when the room phone rang and shattered the silence. The nurse burst into the room and thrust the phone into my hand: “Here, the patient’s aunt wants to talk to you.”

I was at a loss for words. I didn’t know what to say, I had been sitting with this patient for less than an hour and she hadn’t said anything. I wasn’t on the care team and didn’t have a clinical role in this case. I slowly brought the phone to my ear and I heard a kind Texas accent on the other end.

“Well, you must be the volunteer sitting with Jane,” the voice said. It was the patient's aunt.

“Yes, I am,” I replied.

“How is she doing?”

“OK.”

We continued our conversation for several minutes. The aunt described Jane as a person full of energy and passion who stumbled in a series of unfortunate situations. She had a child, a family that cared for her, and a future ahead. The aunt was devastated that she could not be with Jane during this time. Phone calls and care team updates could not give her the connection she needed with her niece. Her guilt and inner turmoil were perceptible through each scratchy vibration coming from the room phone. Jane did not have COVID-19, but because of the pandemic, her support was drastically altered.

As we were talking, I asked the aunt if she wanted to speak to Jane. She exuberantly replied yes, and I put the phone up to Jane’s ear. Almost immediately, Jane became agitated. She coughed, her breathing quickened, and she began to moan. I pulled the phone away and contacted the nurse. The patient continued to vocalize her pain and kept getting louder and louder.

The other side of the phone was just as frustrated. The family member cried out, begging me, a volunteer, to give Jane more drugs. Within 30 seconds, she flipped, demanding that the “deadly poison and toxic drugs” be discontinued, and she promised that Jane would walk out of the hospital that day. Then she screamed a phrase dreaded by all care providers: “You are killing her!”

The room got more chaotic as more people arrived to help. The pain meds weren't immediately kicking in. As Jane's moaning got louder, the nurse suggested we hang up. At that moment, I realized there was nothing I could do to give the aunt the support she needed while her niece lay on her deathbed. I stood motionless in the corner of the room, defeated.

Jane’s circumstances were grim. She had an unsuccessful surgical debridement of infected and necrotic tissue in both lower limbs. She was 30 years old, only three years older than me. She had been on comfort care and hospice for seven days. Her sister had spent nearly every moment with her but, exhausted and exasperated, could not stay without sacrificing the care of her own two children. I sat alone with her for six hours that day. She died 48 hours later. I do not know if she was alone.

These types of situations, where family is unable to be present, are more common now than ever before. A limited visitor policy and strict entrance criteria protect patients, staff, and other community members from potentially harmful contact. But the hospital policies aren’t always what limits family engagement. In the case of our hospital, family members are allowed to be present with patients on hospice care and the aunt could have been present. But, a combination of state borders and work-related restrictions made her visiting next to impossible.

As a medical profession, we have embraced telemedicine for routine care. We have enabled access for patients that would otherwise not have access and kept the population (largely) alive. However, what do we do in this case? Is an iPad screen enough? Can patients feel the presence of a loved one thousands of miles away through a touch screen or a computer monitor? Who is charged with coordinating the computer system? And what happens if there is a glitch? Should you, the clinician, hold a patient’s hand for a family member? Should you hug a patient for a family member?

More fundamentally, some might be asking: does it even matter? We have so many cases like this, it is impossible to help everyone. Should we even try at all? What is the added value? In the moment, the added hassle of setting up the call, coordinating with the family, and checking in seems like just more tasks on an impossibly long checklist of things to do. But if we remove ourselves from the constant clinical buzz, the answer to supporting a patient and their families is always a resounding “yes.”

It has been clearly demonstrated through empirical and objective evidence that there is healing in death. The healing is difficult to verify with the dying, but the loved ones who remain note significant and profound moments of healing that occur during the dying process. Death is the final teacher that ushers in new perspectives, outlooks, and discussions, verbal and non-verbal.

Jane’s image routinely appears in my consciousness and I wonder: could I have done more? I will never forget her aunt’s cry for help and my feeling of defeat. I hope that Jane’s experience will stay with me, and remind me to provide connections for patients to loved ones even during the most dire of circumstances. We as a health care community should make every effort possible to enable these moments and advocate for humane and compassionate treatment at the end of life for all our patients and their families.

Brian Zenger has a BS in Biomedical Engineering and is a MD/PhD student in Biomedical Engineering at the University of Utah. In addition to his clinical and research responsibilities he is the founding volunteer coordinator and current director of the No One Dies Alone program at the University of Utah. He is an active member of the community serving as a volunteer and in multiple leadership positions. He is a 2020–2021 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

All names and identifying information have been modified to protect patient privacy.

Image by Pemimpi / Shutterstock

Click here to see more perspectives on COVID-19 from the Doximity network.

Click here for up-to-date news about COVID-19 on Doximity.