It was the first death I pronounced alone. I plodded down the hall and turned right into the room, my clogs squeaking at the door. The child lay on the bed, legs facing east, with a stillness that could have been deep sleep. What if he was only asleep? What if he was not dead and I called him dead? I froze and wondered what to do.

I recalled my medical school days on my internal medicine rotation. The senior resident was kind and knowledgeable. He eschewed the use of medical terms in favor of common terms, stating that the medical terms created barriers to patient engagement. Instead of leukocytosis, it was a high white count. Squamous epithelial cells and bacteria in a urinalysis meant a lot of skin debris got in the pee. He also taught me how to pronounce death.

The room was still and felt empty despite the bed where the woman lay. No one sat with her. Whether there had been someone at her side and they had left or no one had been with her, I never knew. We were here for the purpose of pronouncing her death. She lay on her back, legs facing south, with a shrunken appearance that made her look gaunt. Her body was cold. The resident showed me a corneal prick — eye poke with a thin object — without a response was a way to verify death. I shuddered in fascination. She was pronounced dead — the date and time called with finality.

The memory rang in my head as I stood in the room with the child. I stepped cautiously towards the child and the family. A parent stood close by, along with the nurse who had paged me. It was back in the days I had three pagers, which, despite my best efforts, pulled my scrubs down my thigh. Pager one: my personal pager. Pager two: the senior pager. Pager three: the dreaded code pager.

I felt small, like the little girl I was when I saw my cat die of rat poisoning, the adults murmuring, Should she see? Maybe it’s for the best if she does, Death is a part of life after all. I made myself walk forward. Poking the eye seemed out of the question. How could I do that to a child as their parent stood there, even if they were dead? Rubbing the chest hard also felt harsh but more humane. I don’t remember doing that either. I do remember approaching the bed and leaning down, my stethoscope hovering and then landing into complete silence — no heartbeat, no sounds. I pronounced the child dead and stated the time, all of which felt painfully arbitrary. He had died before I arrived. Everyone knew it. My role was simply to make it official.

As I pulled back from the bed, I saw the beauty of it all: the child’s rest after months of struggle, the parent’s acceptance, the gentle knowledge of the end’s arrival. The family had known the child would die and had chosen to stop treatment when it became more harmful than helpful. Serenity filled the room, acceptance of what we cannot change and the ability to know.

I consider my own death. Will it be peaceful? Death is something we all ponder while hoping for a quiet, gentle exit from this world. What if I were the woman in the hospital room surrounded by residents and medical students, about to be pronounced dead? I would wish them well and ask them to be kind — kind to me and kind to themselves. The world is full of pain and beauty. You must experience both.

I pause one last time before I leave the child’s room, a room full of light. The empty room of the dead woman fills me, and I wonder if the length of life is not as important as the community of those around us. Maybe what’s important is to be seen and loved. Whenever death comes — be it 7, 37, or 97 — all any of us can ask for is kindness. We all deserve our deaths pronounced with gentleness and our last moments respected, even if they are expected.

What has been your experience with death in medicine? Share in the comments.

Joy Eberhardt De Master works as a pediatrician in Portland, OR. She considers herself to be an American-Mexican and is a highly sensitive person who values beauty and equity. She believes that all people deserve quality health care and that the stories of indigenous people need to be sung loudly. She is a 2020–2021 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

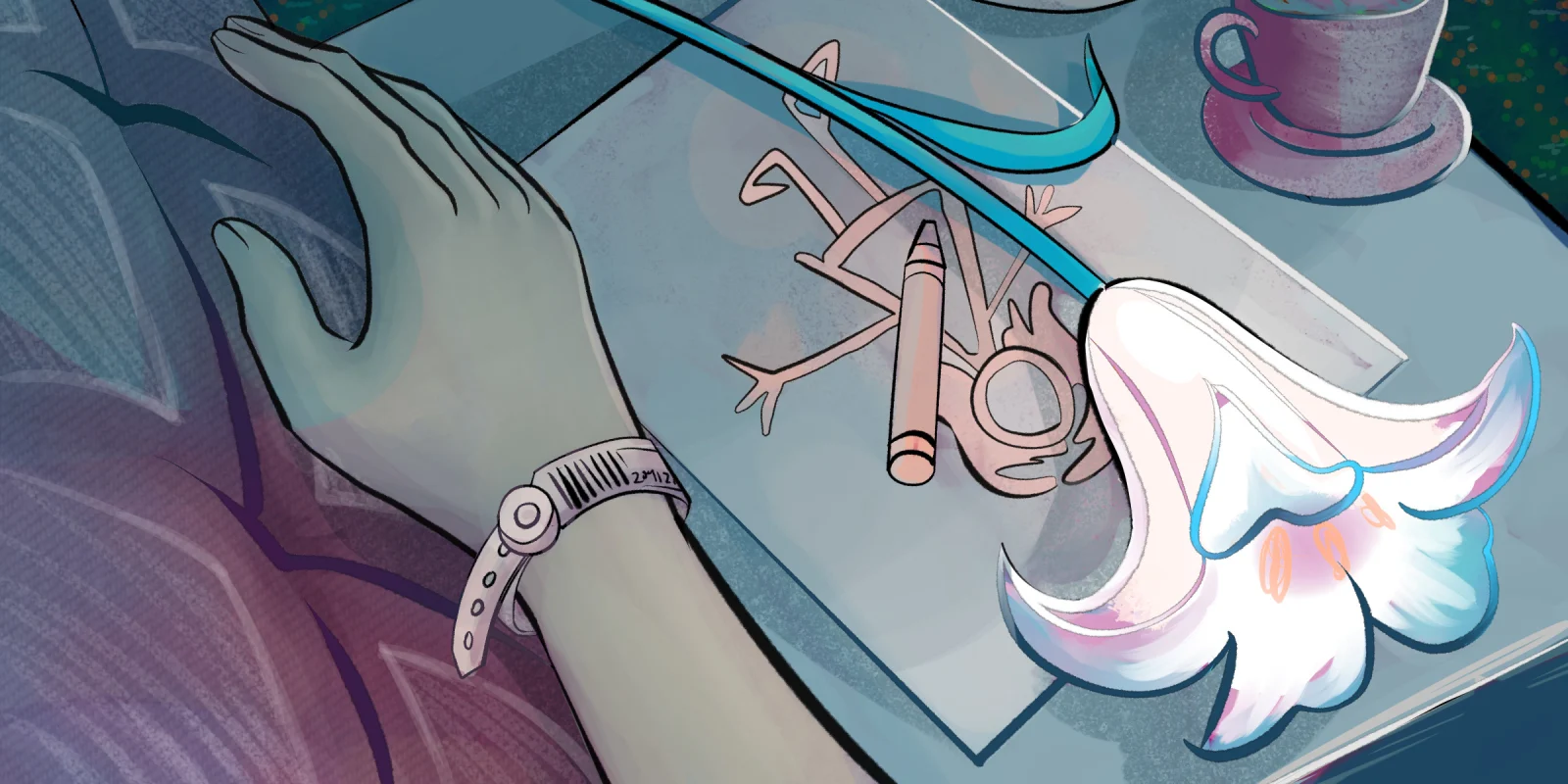

Illustration by April Brust