Innovation has become a virtue in the current culture. There is an evangelical fervor around it. What are TED Talks but tent revivals for nerds? What is the new Apple campus but a cathedral born out of the values of our time? Yet in elevating the more famous innovators and inventions to lofty heights, we lose sight of its very practical and useful daily application. Rather than treat it like inspiration from the heavens, we should approach it as a trait that we all share.

To make it work for you, you have to think of it as a muscle, and put your reps in. Here are a few “training” tips:

- If someone (maybe you) complains about something that feels like drudgery, fix it.

- Fix it like a life depended on it, because it just may.

- Accept that not everyone will get it.

- Do this every chance you get.

Many of us have stories about how we’ve taken opportunities to innovate. Here’s mine. When I was a second-year resident in the ICU back in 1994, we had a patient with HIV infection and necrotizing pancreatitis, requiring an open abdomen with three times a day sterile dressing change. These operations were performed in the ICU where the patient was left with an open abdomen with the pancreas which had exploded with inflammation was packed. The setup was quite hazardous because all the fluid splashing around was infected with HIV, occasionally bloody. But, it wasn’t just a hazard, it was a drudgery. Frustrated with the process, I came on the idea of inserting chest tubes over the packing and under the sticky adhesive drape, and then placing these on suction. I achieved a seal, and the ICU nursing staff was pleased with the invention. Thinking that I could escape the day without another hazardous dressing change, I took the time to pat myself on the back. Of course, I was called stat to the ICU and was dressed down by the head of the ICU for being both lazy and cavalier with the risk to the patient. Interestingly, though, a company came out several years later with a strikingly similar idea, and now negative pressure wound therapy is the standard of care in such situations. In fact, it’s a multi-billion dollar industry.

Of course, money shouldn’t be the sole motivation for innovation. I was motivated by doing less work, reducing the contamination threat for the ICU nurses, and improving care. Many of the best innovations in medicine help the physician care for the patient more efficiently, with better results, and with less suffering. Similarly, the Cleveland Clinic was conceived when American physicians and surgeons, while camped in the vasty fields of northern France during World War I, came to the realization that working collaboratively in a big tent across specialties and disciplines created great efficiencies and rewards, particularly in patient outcome. This innovation, encapsulated in the words “to act as a unit,” brought to the world the first multi-specialty clinics.

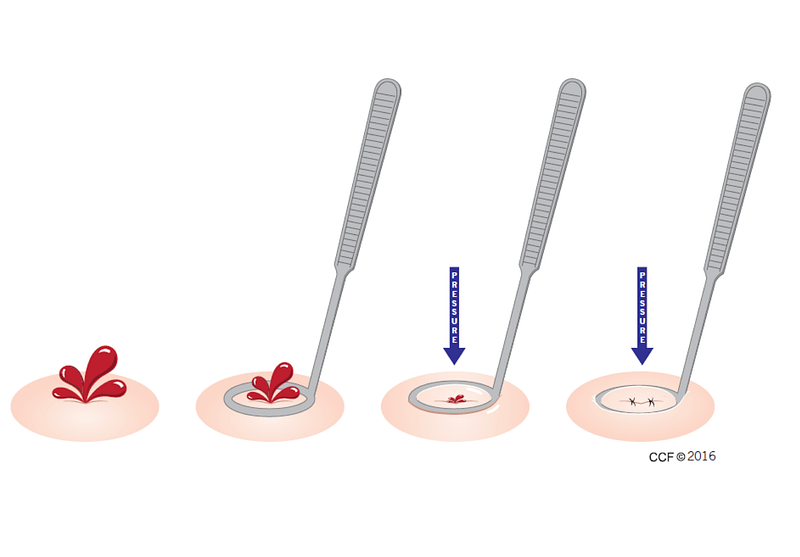

Here’s one last, more-recent example. I am frequently called emergently to an operating room to help control bleeding. Typically, these requests are from surgeons here at the Clinic working on severely scarred, radiated, or previously operated tissues. The typical routine is to dig out the vessel and clamp it, which is challenging because dissecting out the vessel can cause further injury to the vessel with more bleeding. I realized that a circular compressor would control bleeding and provide space for placing a repair suture (figure). When it works, it’s surprisingly easy. You can try it yourself; if you get bleeding from a vein on the skin, compress it with the ring handle of a clamp. This idea (pictured below) has gone to our Innovations office, is now patent pending, and is on track to be manufactured.

We became the dominant species on this planet through the trait of innovation. We could not migrate and survive on all the continents by waiting to grow fur, wings, or gills. Rather, we sallied forth, and we invented our way through deserts, mountains, ice fields, oceans, and jungles. Yet, inventiveness is not common, and it’s too often viewed poorly as a close cousin to cunning, or even sorcery. Innovation also threatens the status quo, because it brings change, and with that obsolescence. Innovation is risky, and the stakes are even higher in medical innovation. But, it’s also the only way we will solve what ails us.

W. Michael Park, MD is a vascular surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic and a 2017–2018 Doximity Fellow. He will be moving abroad to be chief of vascular surgery at Cleveland Clinic Abu Dhabi.