Patient in Room 6001 wants to take 150mg of oxycodone. States they take it all the time at home — 3 a.m. page on call.

My husband doesn’t have COVID-19! You’re lying to pad your numbers and I won’t fall for it!

Hello Ma’am this is [Major Insurance Company]. I know we refused to pay for a nursing home bed for this patient, but if they aren’t discharged today we can’t pay for the hospital stay anymore either…

Safe to say, none of this was what I imagined when I decided to apply to medical school.

This fall, I started my cardiovascular ICU rotation where I spent a lot of anxious nights optimizing ECMO circuits to keep 30-year-olds who were dying of COVID-19 alive long enough to give their lungs a chance to recover. One day, I walked into our cardiovascular ICU workroom to find everyone deep in conversation about how nice it would be to work as a florist instead.

“I mean think about it: weddings are happy, Valentine’s Day is happy, senior prom is also happy!” one of our nurse practitioners said.

“I bet people appreciate you,” agreed the cardiology fellow.

“I bet no one brings a gun to the ICU because they don’t believe flowers are real!” the charge nurse said, alluding to a scary night three men with guns had come to the hospital demanding to see for themselves if a friend really had COVID-19.

I stumbled upon a similar conversation online that week, with residents from all over the country not just joking about becoming a florist, but instead inquiring earnestly about what one could do with an MD or DO, besides practice medicine.

It undoubtedly had been a rough year to work in medicine, but I still couldn’t believe what I was reading. I couldn’t believe people had already been driven away from medicine before residency was even over.

I thought back to the year I applied to medical school for the first time. I’d saved up the money to turn in my applications while I worked as a research coordinator right out of college. The days I spent working with pancreatic cancer patients at my lab had renewed a long-time dream to become a physician. I’d been with people on the worst days of their lives, and had shared in the heaviness and the reverence that comes from a life-changing diagnosis. The physicians I worked with sometimes brought answers, sometimes brought hope, but often, when they could do neither of these things, they simply brought their best for their patients. I refreshed my email incessantly, hoping that one of the medical schools I’d applied to would give me a chance to be like them — to be there for patients like this.

By February, my hope had run out. My friend and I were with some of the medical students from her lab one night when one of them unceremoniously informed me that if I hadn’t gotten an interview by then, I probably never would. I’d suspected as much for several weeks, but hearing this from someone else knocked the last hope of wind from my sails. As we trudged home through the softly falling snow, I let the bitter Northeast cold usher in a terrible thought for the first time: What if I never get to be a doctor?

Tonight I’m writing this — thinking about these patients and the surgeons I used to only dream I could be like one day — after I just spent the day in the OR assisting my attending as we performed a Whipple procedure for a patient with pancreatic cancer. I held the tumor in my hand that used to only exist abstractly in shades of black and white on my research patient’s CT scans.

When I got to medical school, I had a secret fear that after spending so much time and energy trying to get in, the reality of being a medical student might not live up to my hopes. But the years that have passed since my White Coat Ceremony weren’t too good to be true. They were better than I’d even imagined.

This is not to say that every moment has been great, and most physicians speak of “high highs and low lows” as a way to describe our often unpredictable profession. And it’s true that the highs have been higher and the lows have been lower than many of the years of my life that preceded this insane journey. In our world of medical science, we often have the privilege and burden of engaging with the very intangible things that make us human. And this intersection of our medical knowledge with the depths of humanity that few other people will ever experience is precisely where I’ve found what makes life most meaningful to me.

In the very short amount of time I’ve been a doctor, I’ve helped people start their life on this earth, operating on their tiny intestines before they’ve even been held in their mother’s arms. I’ve listened for lingering heart tones after a patient’s last agonal breath during a dimly lit vigil at an ICU bedside. I’ve crash-intubated a patient, and swiftly placed a chest tube for tension pneumothorax, both times living the extreme privilege of watching someone’s vitals stabilize rapidly in a chaotic room, knowing that I was the reason that person was still alive.

I’ve had midnight conversations with an old man about his plans for his funeral and his wishes to die with dignity. I’ve fielded a teenage oncology patient’s fears that he was becoming a burden to his parents, and listened to trauma patient’s family members whisper the unconscionable fear that they killed their loved one — after all, they were driving the car the day of the accident.

An attending spoke to us recently about his reflections on an arduous career. He trained long before the ACGME had work hour restrictions and had sacrificed significant parts of his life for his patients. “I would still do it all over again, though,” he said. He described a folder he had kept over his decades of practicing medicine where he placed letters, cards, and even sticky notes from patients. “I have a phone book-sized folder full of notes from patients. A lot of them thank me for saving their life, but a lot more thank me for doing my best and for being there for them, for listening to them.” He said it was impossible to look at The Folder, at all those lives he’d made a difference in, and still have the audacity to question whether or not this had all been worth it.

In this era of burnout and exhaustion going into another pandemic surge, I’ve found light and fulfillment in these recollections that remind me why that winter day when I realized I wouldn’t get into medical school had been so utterly devastating. Even then, I had a sense of the enormity of what I’d be missing out on, and I’m grateful my medical school took a chance on me during that second application cycle. Just the other day I received an email from a patient who had been critically ill in our ICU during my intern year. He described all the things he had done with this year of life that he and his family thought he might never have. His dad added an addendum thanking our ICU team for another Christmas with his son. I may not yet have a folder of physical letters, but I’ve been collecting these memories all the same, and it’s an unspeakable tragedy to see a system that’s driving my peers — young, idealistic, and compassionate physicians — out of practice before they even get a chance to spend time in this insane, beautiful profession.

How would you defend being a doctor? Share your best pro-arguments in the comments.

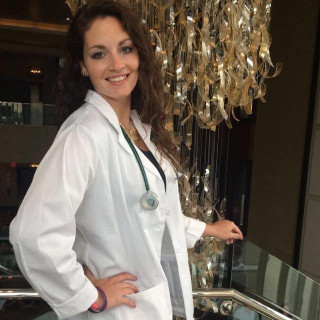

Colleen is currently a general surgery resident in Salt Lake City, UT. She hopes to pursue a career in academic surgery where she can continue teaching, writing, and research in addition to clinical practice. She has an MD/MPH from Tulane University in New Orleans, LA, and hopes to continue to use public health principles to improve surgical outcomes for patients. In her very extensive free time as a surgery resident, Colleen enjoys art, skiing and snowboarding, hiking, writing, dancing, and practicing yoga. Colleen is a 2021–2022 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

Illustration by April Brust