When the Drug Enforcement Agency burst into my small practice in my hometown in West Virginia back in 2009, it wasn’t exactly a shock. In fact, I remember being surprised that it had taken them so long, considering I’d been writing fraudulent prescriptions for 3,000 opioid pills a month. Worse yet, I wasn’t reselling them on the street — which is likely why the DEA didn’t press criminal charges — I was taking them myself.

My addiction had begun with a downward spiral into alcoholism, and eventually I came to rely on the pills to survive. At first, it was to ease the hangovers, then to ease the misery of my work environment, and soon I was completely nonfunctional and suicidal. Eventually, I found my way to a treatment facility and, thankfully, a path toward the work that I love today — helping others win the battle over their own addiction demons.

For me, it was primarily the stress that drove me to drink and eventually use drugs to cope — which is why I’m especially concerned about the impact the pandemic has had on medical professionals across the country. As clinicians, we’ve collectively endured (and many are still enduring) arguably the worst mass casualty event in modern history. As such, it’s no surprise that alcohol consumption has shot up considerably. And some 13% of people admit to starting or increasing substance use in order to cope with the pandemic.

This uptick in pandemic substance use is on top of the already pervasive culture of alcohol consumption in America, and it has many people wondering if their drinking habits could be a sign of something more — a bona fide alcohol use disorder.

For medical professionals, this can be extremely dangerous, with grave consequences ranging from errors that cause negative patient outcomes, criminal implications, and loss of licensure. But many clinicians don’t (or won’t) view their alcohol consumption as an issue. And while there have been some advances in potential genetic testing to determine predisposition for alcoholism, right now, that’s not an option.

Instead, we must rely on circumstantial factors to determine our risk for addiction, and the reality is the risk is higher than you may realize. Five risk factors to consider:

Family history For years, I ignored any potential genetic cause for my own addictive behavior. My addiction was a weakness. I had a choice — I could have stopped drinking or taking the pills. And, for a while, I did have some control. But the truth is, the roots had run deep in my family: my father, grandfather, and uncles were alcoholics. While there’s been ample debate about whether alcoholism is a genetic disorder or a learned behavior, the reality is both are true. Research shows that a person with alcoholism anywhere in their family tree has a 50% chance of becoming an alcoholic themselves.

Age Simply being young is a risk factor. There’s tremendous peer pressure to drink as a social norm before our brain’s dopamine reward system has fully matured (which happens around age 25–26). When you introduce alcohol at an early age, the odds of addiction increase and the earlier it’s introduced, the higher the risk.

Adverse childhood events Certainly, clinicians aren’t immune to traumatic family experiences. Living with an alcoholic parent, as I did, can be a risk factor for alcoholism later in life, but a host of other adverse childhood events can also contribute to the risk. Experiencing any kind of childhood trauma can increase risk of alcoholism, as can living in a household where others experienced this kind of trauma, suffered with mental illness or depression, committed suicide or went to prison.

Comorbidities Other health factors, such as chronic pain and mental health issues, can increase susceptibility. Known in addiction treatment as “dual-diagnosis,” it’s extremely common for those with ADHD or depression, anxiety and PTSD — all of which are common in the medical field by the nature of our work — to self-medicate with alcohol. Unfortunately, alcohol not only exacerbates these comorbidities, but it can also introduce new ones, such as poor sleep quality, high blood pressure, liver disease, and more. In my case, I began to distance myself from everyone who expressed concern, which only fueled my loneliness and desperation.

High tolerance This is a serious risk factor because it actually exposes you to much higher doses of a known toxin, and a high tolerance means it takes more and more for you to feel the effects. While you might find comfort in the fact that you can drink a lot, not “act drunk,” and still function well enough to do your job, the reality is: the higher your tolerance, the greater your risk of addiction.

So, what should you do? Recognize that even occasional drinking puts you at risk of alcoholism, especially if you have a family history combined with any other risk factor.

Next, challenge yourself to abstain for a month, then six months, even a year. Ask yourself: is your life better now than it was before, when you were drinking? Most people find they had no idea just how much even casual alcohol consumption was affecting them socially and financially, compromising their health, or contributing to risky behavior.

And, if you discover that you cannot commit to or complete even a short period of abstinence, it may be time to talk to an addiction specialist about potential alcohol dependence. Start by finding a treatment center — confidential help is available 24/7 and may be covered by insurance.

As medical professionals, we’re in the business of taking care of others. But we aren’t superhuman. It’s time to prioritize our own health the same way we prioritize the health of our patients.

Have you or someone close to you struggled with substance abuse? How did you overcome it? Share your success with your peers below.

Dr. Charles Smith is an Addictionologist at Recovery First Treatment Center in Fort Lauderdale, FL. He was previously a family medicine physician in West Virginia for 26 years before treating the disease of addiction. Spurred by his own recovery, Dr. Smith is an expert on the biological aspect of addiction and the intricate effects of alcohol and mind-altering substances on the brain.

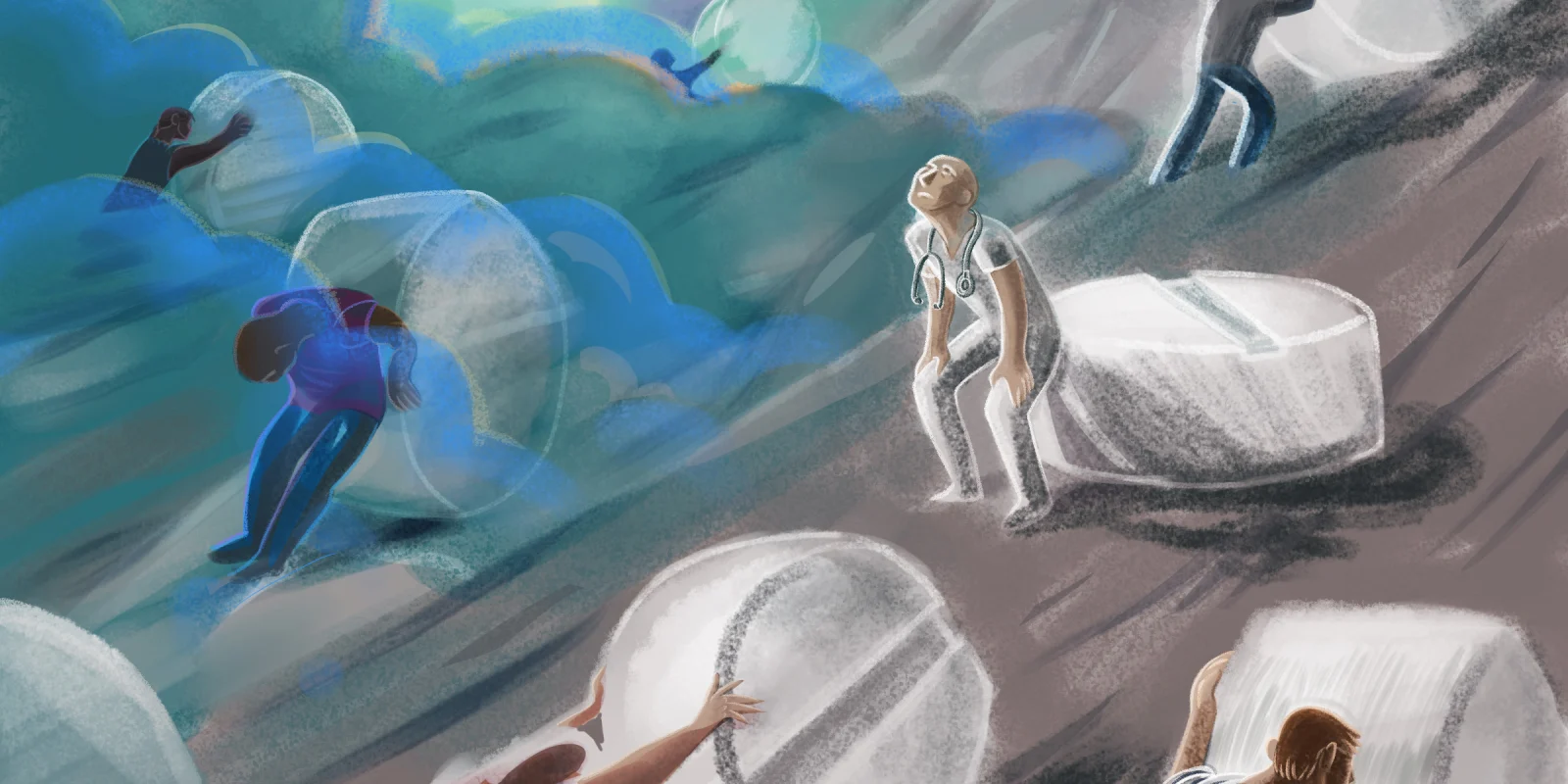

Illustration by April Brust