Before COVID-19, I left the practice of medicine for what would turn out to become an entire year. Then, the pandemic happened, and I found my way back to clinical practice. During that time away from medicine, I discovered five things that transformed my life and practice. With the guidance of a life coach, intensive reading, and exploration of literature, I found a new way of seeing our hearts and bodies as humans in the medical profession. Here are five lessons I learned, in the hope that they might help others.

Perfectionism Doesn't Make You Perfect

If perfectionism isn’t an unwritten rule in our profession, it’s, at minimum, a personality tendency that is heavily reinforced. When I first faced my perfectionism, I tried to argue that it was a good thing. Of course I’m a perfectionist. I’m a physician. We have to be perfectionists. If we’re not, people die.

But with my coach’s guidance, I learned, little by little, that one of the dangers of perfectionism is that it leaves no room for self-compassion. For a physician who prided herself on her empathy, discovering I had no self-empathy came as a rude awakening.

But learning to embrace imperfection is not an overnight task. For anyone just starting out along this path of self-discovery, a great place to start is with the seminal work of Brené Brown.

It was only after I accepted 1) that I was a perfectionist and 2) there was another way to live that I came to understand my perfectionism had been an inflexible barrier to the practice of self-compassion.

Self-Compassion Is Essential and Isn't What You Think It Is

Yes, self-care is great and all, but self-compassion, or self-empathy, isn’t necessarily bingeing the latest Netflix series and unlimited ice cream (although those things have their value, too). Self-empathy takes practice and hard work. It requires showing up for yourself, even when it feels like it might be easier not to. Experts in self-compassion, such as Kristin Neff, PhD, and those behind the Compassion Fatigue Awareness Project, have described this as “putting your own oxygen mask on first.”

We might commit to it in that wellness seminar, but do we follow through? Or do we instead make empty promises? Because secretly, we believe that we’re superhuman. Sure, we’ll get to our own oxygen mask soon, very soon, but first, we have time to take care of one more thing. …

Self-compassion means gently but firmly reminding ourselves that we are not superhuman. We need to eat, sleep, rest, breathe, exercise, play. We need to attend to our own emotions and bodies every day, even when it feels like doing so might slow us down, or let down others. Because in the end, it won’t, and it doesn’t. In short, we need to be kind to ourselves.

If you struggle with that like I did, I recommend reading Dr. Neff’s book "Self-Compassion: The Proven Power of Being Kind to Yourself." (I also recommend going to the author’s website to take a self-compassion quiz. But if you score low, like I did, be gentle with yourself. Diagnosing the problem is the first step toward healing.)

External Validation Will Never Equal Happiness

For me, it became clear that there was a sneaky triad in my life that had set the stage for physician burnout. It consisted of the above two issues — perfectionism and lack of self-empathy — but the third was more subtle: a subconscious need for external validation.

I’ve come to believe that most physicians experience this triad — as a function of our own personality tendencies, combined with the covert and overt reinforcement of these factors throughout our medical training. Breaking free of it will be different for each person, but crucial for me has been learning to embrace vulnerability as a strength and not a weakness. Only by embracing our vulnerability can we live as our authentic selves.

As Brené Brown writes, “Vulnerability is the birthplace of love, belonging, joy, courage, empathy, and creativity. It is the source of hope, empathy, accountability, and authenticity. If we want greater clarity in our purpose or deeper and more meaningful spiritual lives, vulnerability is the path.”

For more of a physician’s experience on vulnerability as a path, I learned from Adam B. Hill, MD’s "Long Walk Out of the Woods: A Physician’s Story of Addiction, Depression, Hope, and Recovery." (If you don’t have time to read the whole book, start here.)

The Heart Has a Back Door

This one was a true game-changer for me. Oncology is a field that draws empathetic people, but at no time in my training was I taught how to cope with the deluge of emotional input that comes with serving others in our profession. In my coaching sessions, I learned that it’s possible to keep one’s heart open to those in need, but at the same time allow the things that don’t belong to us to flow through and out. We don’t need to build walls, but we also don’t need to adopt burdens that are not ours. Especially when that’s not what our patients are asking — or needing — from us. But if we’re never given the tools or taught the strategies in our training, it’s difficult not to internalize others’ pain.

To learn more about this, I recommend the book "Self-Care for the Self-Aware: A Guide for Highly Sensitive People, Empaths, Intuitives, and Healers."

By keeping the back door of the heart open, I’m learning to stay present in the moment with my patients, but to release the emotions afterward. Which was the step I was missing, and the essential piece needed to then be present for my family when I return home.

The Game Is Rigged

The health care system is broken. We don’t have to pretend anymore that it isn’t. I want to write that again. The health care system is broken, and we don’t have to pretend anymore that it isn’t.

I hadn’t fully understood the personal stress of working in a broken system (I’m referring here to pre-pandemic; a discussion of the innumerable additional pressures from COVID-19 is beyond the scope of this article) while still trying to pretend everything was fine until I recently read the book "Burnout: The Secret to Unlocking the Stress Cycle" by Emily Nagoski and Amelia Nagoski. (For an audible overview of the book, check out also this Brené Brown podcast.)

As they write, “Just knowing that the game is rigged can help you feel better right away.”

Their book is not specifically about burnout in health care, but it extrapolates very well to physicians, especially female physicians. The authors don’t shy away from a candid discussion of the ways in which the patriarchy contributes to burnout. But if the game is rigged, how do we win?

Not by proving to others that the system is wrong — because we know now that’s a given — but by proving our own character. By showing up anyway to do the right thing. Not for the system, but to hold true to our authentic selves. By not letting the brokenness erode our purpose.

Before, I didn’t have the tools or understanding to prevent this, and I did lose my purpose for a time. But ending up as a burned-out physician allowed me to find my way back. By doing the best that I could, in the circumstances that I found myself. One moment at a time. That’s it.

There’s a validation to recognizing that we’re all working in a broken system where the game has been rigged. For me, this recognition was what helped me to decide to return to it anyway. And to decide to make myself vulnerable by sharing my experience with others. Because one of the key ingredients for self-compassion is a recognition of our common humanity.

I am more and more convinced that the way many of us were trained — to suppress emotion and evince a superhuman outer aspect — was profoundly flawed and incompatible with a common humanity. Because it turns out that emotions live in the body. They are what make us human and allow us to connect with others. Rather than putting our bodies and emotions in a straitjacket to conform to impossible outer expectations, we can recognize our vulnerability as an integral part of our humanity. By doing so, I’m discovering that I still do want to be a physician. But only as my authentic self.

What are some lessons you've learned outside of medicine that have made you a better clinician? Share in the comments.

Jennifer Lycette, MD, is a medical oncologist in rural community practice on the North Oregon Coast. Her perspective essays have been published in NEJM, JAMA, JCO and more. Dr. Lycette was a 2018–2019 Doximity Author, a 2019–2020 Doximity Op-Med Fellow, and continues as a 2020–2021 Doximity Op-Med Fellow. You can find more of her writing at on her website, and follow her on Twitter @JL_Lycette. Opinions are her own.

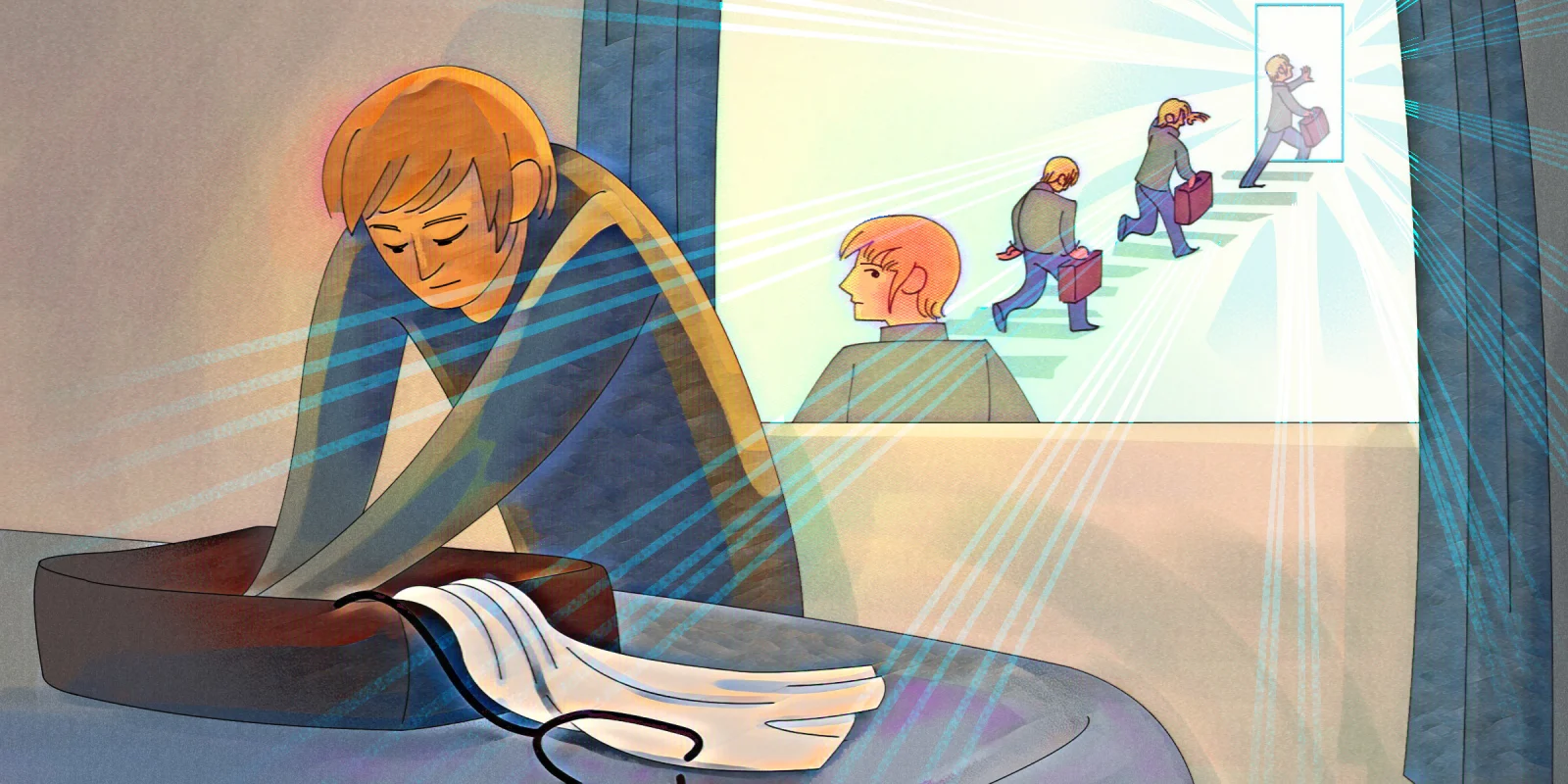

Illustration by April Brust