I skimmed through Mr. Tyron’s admission note. He was a 42-year-old African American man who was experiencing homelessness and had been admitted for alcohol withdrawal. The note reported that he had been in an alcohol rehab program but had now relapsed. My first impression of him was that he seemed to be someone who had made some bad choices and was now facing the consequences. Once I got to know Mr. Tyron, however, I realized that the simple narrative I’d created for him misrepresented his story, which had been shaped by structures and systems in addition to his own individual decisions. Practicing “structural competency” enabled me to better understand Mr. Tyron and to treat him more compassionately and effectively.

Structural competency refers to a health professional’s ability to “recognize and respond with self-reflexive humility and community engagement to the ways negative health outcomes and lifestyle practices are shaped by larger socio-economic, cultural, political, and economic forces.” When faced with patients like Mr. Tyron, who was admitted for a condition seemingly attributable to his own bad behavior, it can be tempting to blame the patient. Over time, the frustration of treating patients who seem complicit in their own illness may contribute to burnout and compassion fatigue. A structural competency perspective focuses on the structural barriers that constrain patients’ behaviors and encourages clinicians to connect structurally vulnerable patients with social services and to advocate for policies that promote health equity. Meeting Mr. Tyron highlighted the tremendous importance of applying a structural competency lens to all of my patients’ stories.

The first piece of his story that Mr. Tyron shared with me was that he was a veteran. He had served in the Army years ago but had become disabled. Unable to work and out of touch with his family, he was able to rent a room from a friend for many years. Then, however, his friend became ill and died. Unable to find another place to rent, grieving the loss of his friend, and lacking any other social or financial support, Mr. Tyron had tried living in a shelter but experienced violence and theft there. As a result, he felt safer living on the street. He hadn’t wanted to start drinking, but because his companions on the street drank, he started drinking too. Soon the alcohol use spiraled out of control.

Last year, Mr. Tyron had finally found his way into a Veterans Affairs-affiliated inpatient alcohol rehab program — a “turning point,” he said — but due to the pandemic, the rehab program had been shut down. He was discharged without a sustainable follow-up plan, and thus returned to the street and alcohol, which had resulted in his current hospitalization. As we talked, Mr. Tyron asked repeatedly about when he might be able to start another alcohol rehab program. He told me about his hope to one day get back in contact with his brother, who lived in another state, but only “once I have my life together.” Mr. Tyron did not lack the individual will to better himself, but because of structural failures — the dearth of affordable housing for someone on disability, the closure of his rehab program, and the lack of accessible follow-up care — he was unable to lead the healthy lifestyle he desired.

For structurally vulnerable patients with highly stigmatized illnesses such as alcohol use disorder or other substance use disorders, I find that using a structural competency perspective is incredibly valuable. Such a perspective helps me to not only better understand the patient, but also helps me partner with the patient to develop a holistic, multidisciplinary treatment plan. Beyond individual encounters, this perspective also motivates me to advocate on my patients’ behalf for policies and systems that better serve the most vulnerable. Finally, it protects me from compassion fatigue as I embark on what I hope is a lifetime of caring for patients like Mr. Tyron.

How do you protect yourself from compassion fatigue? Are there perspectives or lenses that help you treat your patients more holistically? Share your thoughts in the comments.

Ashley Wu is a fourth-year medical student at Weill Cornell Medical College. She plans to specialize in psychiatry and, in her spare time, enjoys baking sourdough, finger crocheting, and attempting various arm balance yoga poses. Ashley is a 2020–2021 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

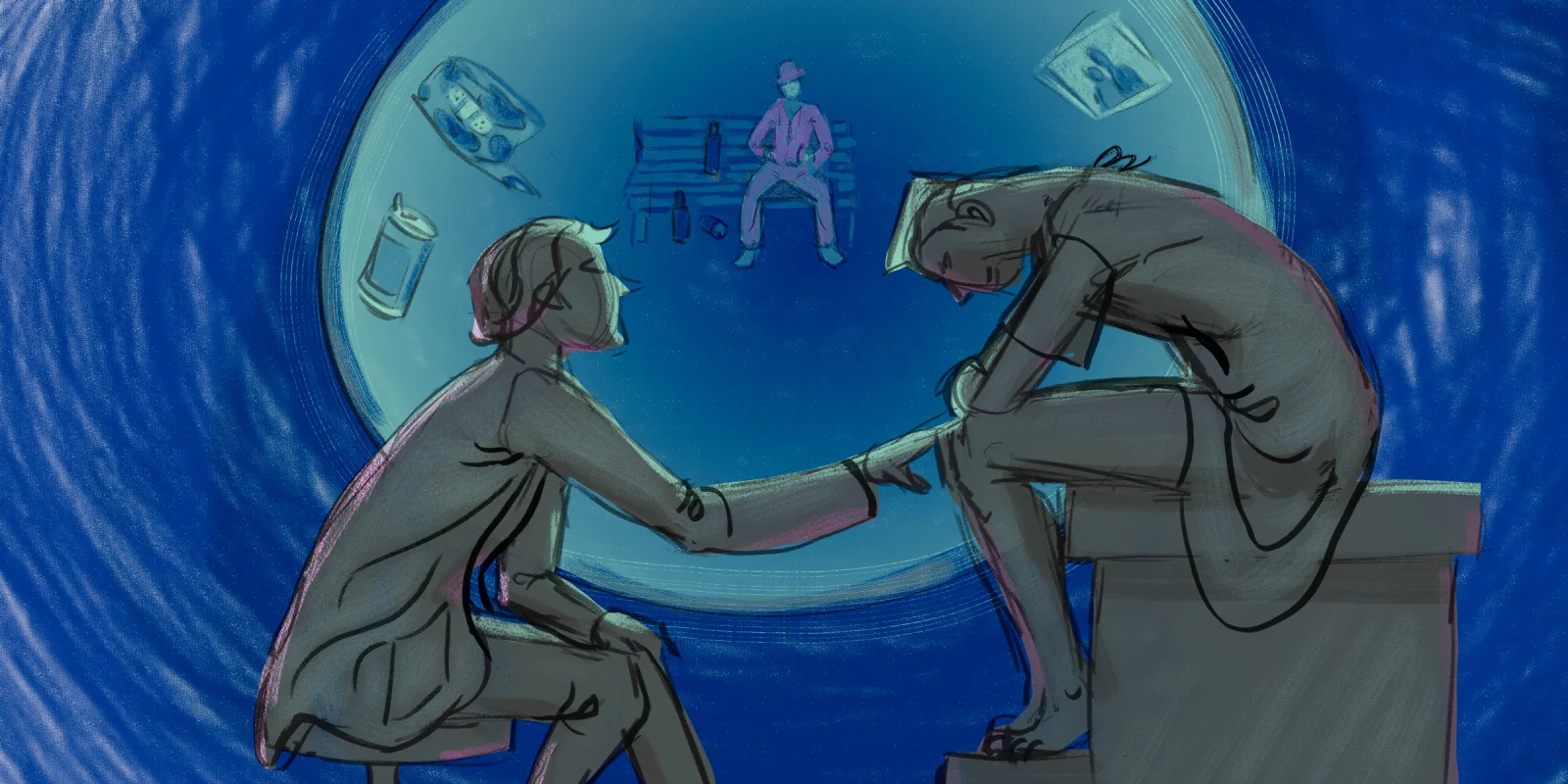

Illustration by Jennifer Bogartz