Fresh out of nephrology fellowship at Wilford Hall USAF Medical Center in San Antonio Texas in May of 1981, I was assigned as the only Air Force Nephrologist to Clark Air Base, 11,000 miles and 11 time zones away on the island of Luzon in the Philippines. I was to start work at Clark in August of 1981 and was to be there until August of 1984.

There I had a six-day-a-week, 12-station dialysis unit to run solo, eight half-day nephrology clinics each week, and admitted every third night to a general medical inpatient service.

To say the least, it was busy.

But, there were some real pluses. My wife found a wonderful domestic helper who became a beloved member of our family, knowledgeably guiding us and dealing with an off-base environment where English was spoken when things were going well, and Tagalog suddenly became the only means of communication when there was a disagreement over prices or fees.

Despite the high work tempo, we thoroughly enjoyed most of our time there. But, the shadow of a growing plague began to fall across the place, its deadly effect corroding some of that enjoyment.

Shortly after arriving and settling in, I began to encounter a series of mystifying cases. Young sailors, arriving on ships that had stopped at various Southeast Asian ports — ports that harbored their own notorious fleshpots — were showing up at Clark on referral from Subic Bay with fevers, weight loss, lymphopenia with lymphadenopathy, rashes, and other symptoms. These findings were inexplicable, despite full workups available at that time. Even blood samples sent for tests came back “negative” or “non-diagnostic." Some troops wound up septic in the ICU with multiple organisms our microbiology lab had never encountered before, even when they could identify the multiple bugs simultaneously in the blood, which was a disturbingly frequent situation.

At one point in mid-1982, I remember getting on the military’s operator-moderated telephone system in the middle of the Philippine night and calling through several jumps back to the CDC in Atlanta. There, I spoke with an ID expert, echoing back and forth down the 11-time-zone telephone link, asking if any other military bases were seeing similar cases. No luck. No other military facility was reporting similar cases. I remember going back to bed thinking, “How can we be the only ones? What’s so unique about this place?"

Years later, as we watched the film “The Band Played On,” my wife reminded me of the night I had come home from the hospital almost in tears after losing a 20-year-old sailor to rampant Mucor sepsis. I felt overwhelmed and lost, facing what seemed to be an epidemic of implacable lethality that was taking out young military folks despite every antibiotic and antifungal I could throw at them.

One young troop had onset of nephrotic syndrome in 1983, and I did a kidney biopsy in an attempt to find the cause. Gowned in a lead apron, with the patient lying prone on a fluoroscopy table, a pillow-roll under his abdomen, I got two breath-held cores of his kidney with a Jamshidi needle, dropped them into a thermos bottle filled with liquid nitrogen, un-gowned, and rushed them to the flight line, where I found a crew preparing to take off for Hawaii via Guam. I instructed them that the bottle had to arrive at Tripler before the liquid nitrogen had evaporated, and if they were delayed at Guam they would have to call the military hospital there to get the liquid nitrogen refreshed. After handing it over to them, I waited anxiously for word.

Three days later, in the early morning hours, the base operator apologetically woke me up in my base quarters and informed me that a doctor in Hawaii was insisting on talking to me. I thanked her, took the phone, and was advised by the pathologist that, “This is focal segmental sclerosis (FSGS), but it is the weirdest one I’ve personally seen. The glomeruli look like they’ve just imploded on themselves. It’s like collapsing FSGS, but I’ve never seen one like this before.” I thanked him and arranged for the young sailor to be air-evacuated back to the U.S.

It would be 1986, two years following my return to the U.S., that I would encounter the same sailor in a hospital hallway.

“Hey Doc,” he greeted me, "Do you remember me? You did that kidney biopsy on me at Clark. It turns out I have AIDS."

I was stunned. Although by 1986 it was known that collapsing FSGS was a hallmark of HIV infection, when the puzzled pathologist and I had conferred over the phone in 1982, it was all still a set of unconnected strange facts that made no sense.

These memories, of being clueless in the face of a new and deadly condition, profoundly changed my prior sense of medical omnipotence. They are still strong today, 32 years later. Faced with something we could not identify, did not understand, and were utterly powerless against, I developed a sense of the fragility and incompleteness of our knowledge, and the way we could be just as helpless as the physicians in John Barry’s book “The Great influenza” in the face of rapidly-spiraling death.

It is a lesson not to be forgotten in a world where antimicrobial evolutionary pressures, random mutations of an influenza virus, or genetic-editing technology put to dark uses could once again place us in a strange and frightening place, face to face with an unknown emerging disease.

Dr. O'Neil is a nephrologist who spent 30 years in the Air Force, four years post-911 working as a Federal Civilian for DoD and 11 years at the James Quillen VAMC in Tennessee. He enjoyed assignments in the Philippines, Panama, and several locations in the States, and learned much from each one.

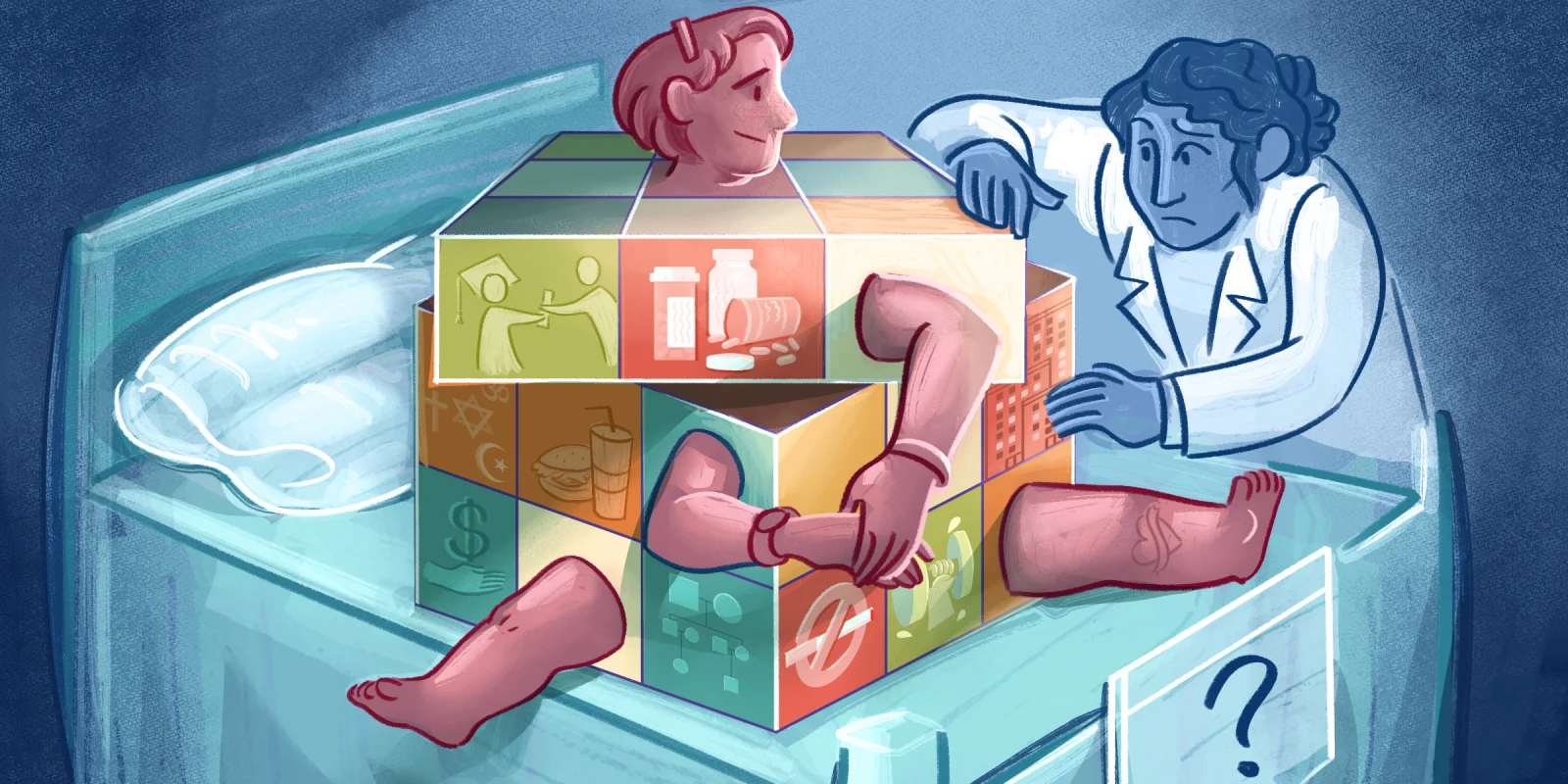

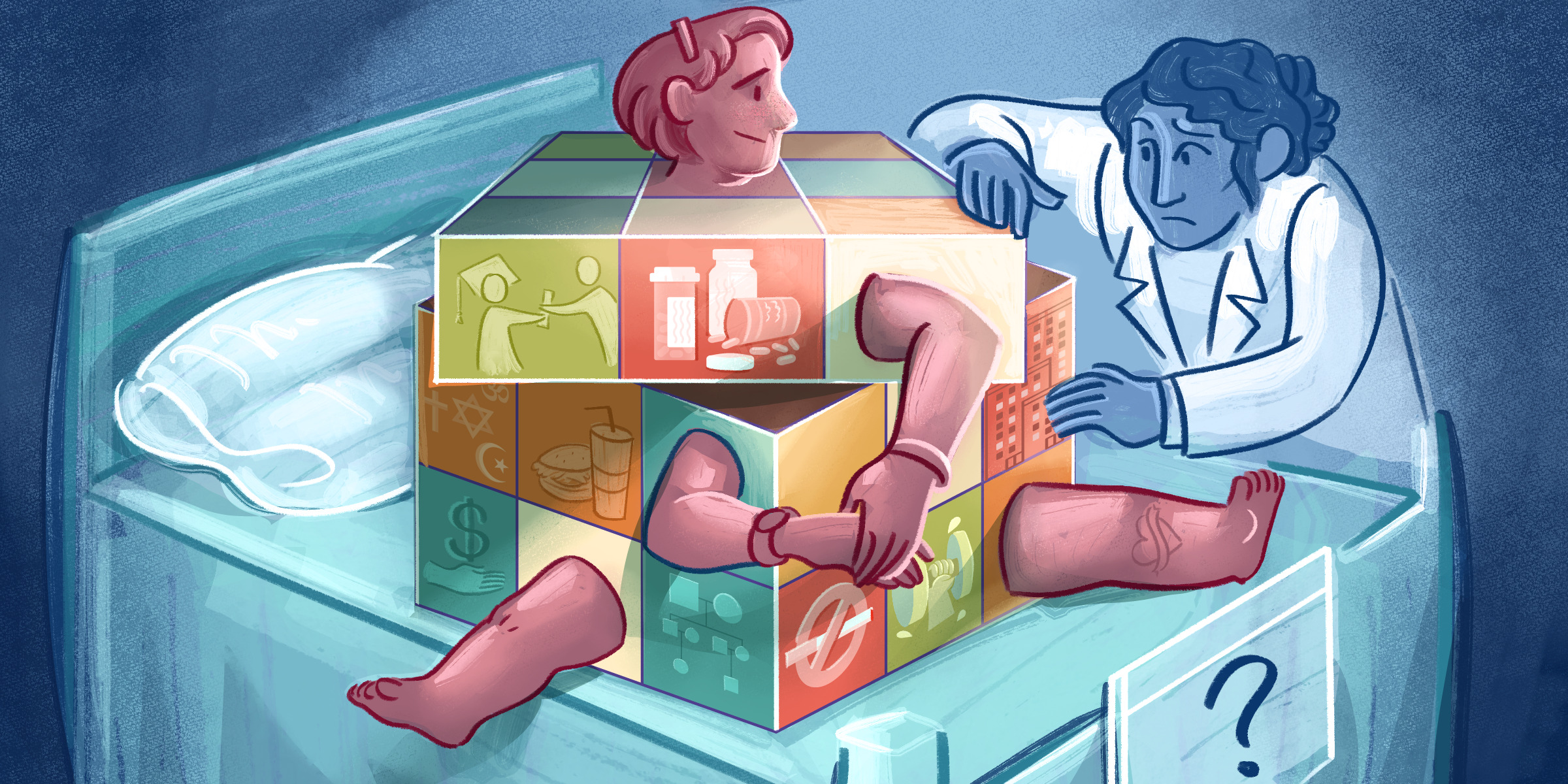

Illustration by April Brust