The head nurse came over to us in the hallway. Years of experience on the wards were evident in the wrinkles on her face that coalesced into a mildly jaded expression. I stood with a group of residents in the hall who were discussing a patient we had just seen. As a first-year medical student, I did not have much to add to the conversation. The nurse waited for the senior resident to finish his thought before saying, “The patient in bed five’s blood pressure is down to 30.”

The senior resident, my mentor, asked, “systolic?”

Without waiting for an answer, he briskly walked down the hall. We entered room five with another resident close behind. A small fleet of nurses also appeared. I walked to the far wall and tried to take up as little space as possible.

The patient was a middle-aged man who was HIV positive. He came to the hospital earlier that day because he was short of breath. He was presumed to have a recurrence of endocarditis stemming from a stent in his heart. He had already crashed once earlier that day. Now, his heart and lungs were being controlled by machines. His skin was pale and turned ashy gray at his hands and feet. His eyes were wide open. He had the pupillary reflexes of a dead man.

I had been in room five only an hour before. I watched a critical care fellow adeptly place a central line in the patient as he needed more ports to maintain the delicate balance of drugs that were keeping him alive. He was hooked up to various machines that beeped regularly, fading into the background.

Now, the monitors beeped louder, emerging from the background to make their urgency known. Young nurses swarmed in and out, retrieving things from the stockroom. One of them got the crash cart ready. The head nurse looked bemused, “What are you getting that for? It’s not going to do anything.” Then she rattled off some numbers and labs that I didn’t understand. Apparently, this man was toast, and everybody knew it.

When my mentor had previously asked the patient about his code status, the patient told him to do everything. So, even though it looked futile, the choice was clear: do everything.

The head nurse said, “Well alright then. Who needs to practice CPR?”

As the most senior doctor in the room, my mentor took the lead, charging people with various tasks. One person was sent to contact the family. Another, to prepare the defibrillator. Two others prepared to take turns doing compressions.

The crowd of nurses in the room had an oddly cheerful mood, cracking jokes and making light of the situation. The two residents would laugh too, but I detected an undertone of grave concern. It felt odd. In the movies, when someone crashes, everyone is on their toes. People are running around and barking orders, wearing solemn expressions. Apparently in real life, this was business as usual in the ICU.

I looked on in awe as my mentor called the shots. He conducted an orchestra, playing instruments of syringes and shock paddles. After the first shock, a horrible odor wafted through the room. People pinched their noses and grimaced.

“You shocked it right out of him,” one of the nurses chuckled.

It felt like God was making a really inappropriate joke.

After a while of seesawing vitals, my mentor called out, “OK, we’ll do compressions for 10 more minutes, and after that we’ll call it.”

All told, the man died. Well, he didn’t really actively die. Rather, they stopped trying to save him. Technically, his heart was still pumping and his lungs were still breathing, but all of that stopped with the flip of a switch. In a way, it was like he was dead the whole time, but we promised to “do everything” to save him. So, we did. We kept saving him until there was nothing new to try. Then, he was finally allowed to die.

After, everyone went back to their posts. Business as usual.

Kathleen Chung is a fourth year medical student at Alpert Medical School of Brown University. She is planning to pursue a residency in ob/gyn.

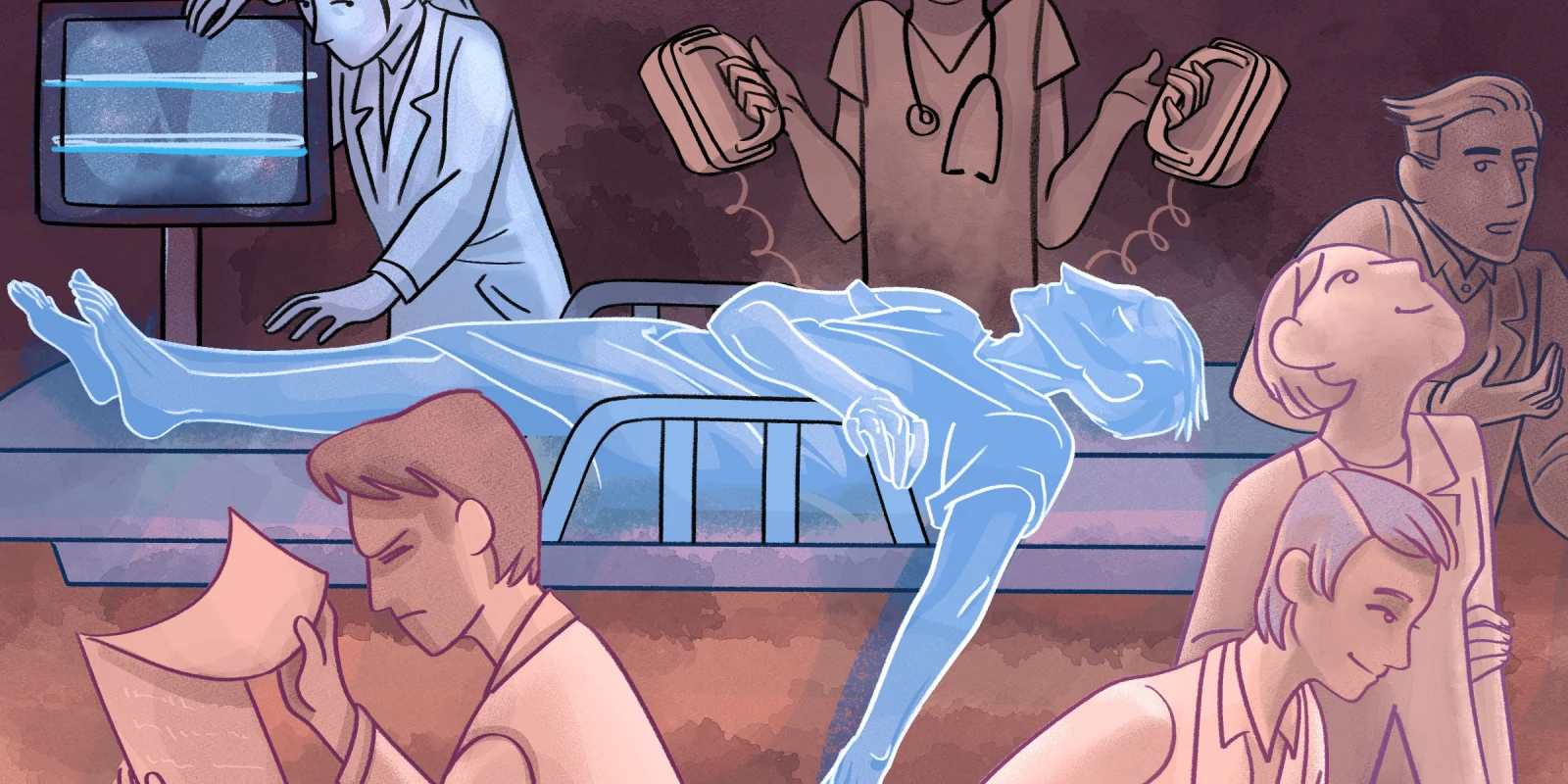

Illustration by April Brust