I first met Sophie during a routine physical visit. As with all my primary care patients, I asked her how the pandemic had impacted her life. She was a computer engineer who worked from home and felt socially isolated from the world, which worsened her depression. She had also had a few distant relatives pass away from COVID-19.

“I’m so sorry,” I murmured, “I can’t imagine what it’s like to have a loved one pass away.”

We chatted about her acute medical issues and medical history. Finally, we arrived at the preventative screening portion of the visit.

“Looks like you’re up to date on your cervical cancer screening, so no pap smear for you today. I see that you haven’t received your COVID vaccine yet. Are you interested in a referral to the vaccine clinic?” I asked.

“No, thank you,” she replied, “I’m not planning on getting the vaccine any time soon.”

Curious, I started to engage her in conversation about her reservations. Sophie is the daughter of Haitian immigrants and relayed stories of watching doctors experiment on her parents, and talked about how that generational trauma has persisted in her family. “I’ve never gotten the flu before. I had a bad reaction to the flu vaccine once so never got it again. I’m still wearing masks and socially distancing in public spaces, so I’ll hold off on the COVID vaccine, thanks.”

Although there are myriad reasons why a person may choose not to get vaccinated, many are rooted in misinformation or systemic oppression. In fact, there is a large overlap between our society’s marginalized individuals and the unvaccinated. Black, Latinx, Indigenous, LGBTQIA+, immigrant, and other communities have lost trust in the government and institutional medicine in response to historical and current events like the Tuskegee study, the AIDS crisis, and ICE’s enforcement and removal policies. Racism and classism play a huge role in vaccine choice, as does access to misinformation versus accurate scientific data.

Regardless of the reason someone remains unvaccinated, it is not the health care professional’s place to dole out judgement on who deserves medical care. Rather, we are trained to provide care that is clinically necessary. We only ever get a glimpse into our patients’ lives — I am barely able to spend 30 minutes with my primary care clinic patients! To understand the mental calculus that individuals take to arrive at their COVID-19 vaccination decision is asking clinicians to understand their prior lived experiences within the biopsychosocial model during a brief, sterile clinical interaction. Much as we shouldn’t deny medical care to the overweight person for developing diabetes, we cannot deny or ration care based on our limited understanding of a patient’s culpability. No matter the perceived moral failing that clinicians may secretly (or not so secretly) assign to their patients, we cannot ignore the structural forces, like poverty and racism, that contribute to disease.

Even with all of that in mind, it can still be difficult to provide medical care to unvaccinated patients when vaccines are available as a proven method for preventing COVID-19 infections and hospitalizations. To help me navigate my discomfort in caring for these patients, I have found the concept of harm reduction to be helpful. Even before becoming an addiction medicine doctor, conceptualizing patient care in terms of harm reduction helped me battle burnout.

Harm reduction is rooted in minimizing the negative effects associated with substance use (e.g., alcohol, opioids, cocaine, etc.) without requiring complete abstinence. Principles of harm reduction include respecting the patient’s choice, committing to social justice through collaboration with the patient, and avoiding stigma. Examples of harm reduction strategies in the addiction field include needle exchange programs; safe consumption sites; and providing free safe injection kits, medications for substance use disorders, and regular testing for HIV, Hepatitis C, and other infectious diseases. Harm reduction can be translated to other aspects of medicine, too. In the case of COVID-19, it can mean fighting misinformation, and providing free surgical masks, COVID-19 testing, space for social distancing, and patient-centered education about the ever-evolving pandemic.

I find the following steps helpful when discovering that a patient is unvaccinated (though, granted, I have the luxury of being able to have full-fledged conversations with patients who are not critically ill):

(1) Elicit the illness framework that the patient operates in. Attempt to understand the previous experiences that have led them to their choice. Express curiosity and reserve bias about why they chose not to be vaccinated. Avoid stigmatizing or judgmental language.

(2) Align the patient’s goals and values with your medical recommendations. Find out what they care about; it may be the health of their loved ones, living to see their grandchildren get married, or earning enough money to buy a house. Discuss the risks and benefits of the COVID-19 vaccine and how it fits with their goals and values.

(3) Discuss harm reduction strategies. For patients who are unvaccinated, emphasizing the importance of wearing masks and social distancing is key. If the patient is interested, provide education about the virus, the vaccine, and information about COVID-19 testing.

(4) Communicate an open-door policy. This discussion does not have to be one-and-done. For those who are on the fence about vaccination, ask if you can revisit the conversation at a later time.

Recently, I was caring for a patient in the addiction clinic. He was a white man who grew up in the Boston area with a personal history of complex trauma and family history of substance use. He had started using heroin at the young age of 13 and had not graduated from high school. During our conversation, he shared with me that his wife and children had all come down with a flu-like illness a few months ago. They thought it might have been COVID-19 (they never got tested), so the entire family self-isolated for two weeks. He had read online that “Big Pharma” created the vaccines to generate profit, and thought that he would be protected via natural immunity. In our visit, we discussed the importance of protecting his family with vaccines, and the CDC’s recommendation to get vaccinated regardless of natural immunity. He expressed hesitation and declined the vaccine. I applauded him for self-isolating, wearing masks, and keeping others safe. I let him know that we were happy to give him information about COVID-19 vaccine clinics if he decided to get vaccinated. Although I wasn’t able to convince this patient to follow my medical advice, we were able to have shared decision-making around harm-reducing strategies.

Everyone deserves a chance. When I meet a patient who has liver failure from drinking, I continue to offer medications to reduce alcohol cravings, recommendations for liver transplant when appropriate, and referrals to recovery programs. When I admit someone with endocarditis from injection drug use, infectious disease doctors, cardiologists, and cardiac surgeons will discuss the medical criteria for heart valve replacement surgery. When I meet a patient who is unvaccinated, I continue to deliver compassionate and harm-reducing care. Much like the stigma associated with people who use drugs, there can be stigma associated with those who are unvaccinated. We must continue to dispel this stigma while simultaneously advocating for widespread vaccination.

The next time I see Sophie, I will be sure to revisit our vaccination conversation.

How have you navigated conversations with patients who can’t be convinced to follow your medical advice? Share your stories in the comments.

Sunny Kung is an addiction medicine fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital. She completed her internal medicine residency at Brigham and Women's Hospital and medical school at the Pritzker School of Medicine University of Chicago. Originally from California, she is a Taiwanese first-generation immigrant interested in caring for minoritized populations, immigrants, patients with substance use disorders, and those experiencing homelessness. Sunny is a 2021–2022 Doximity Op-Med Fellow.

All names and identifying information have been modified to protect patient privacy.

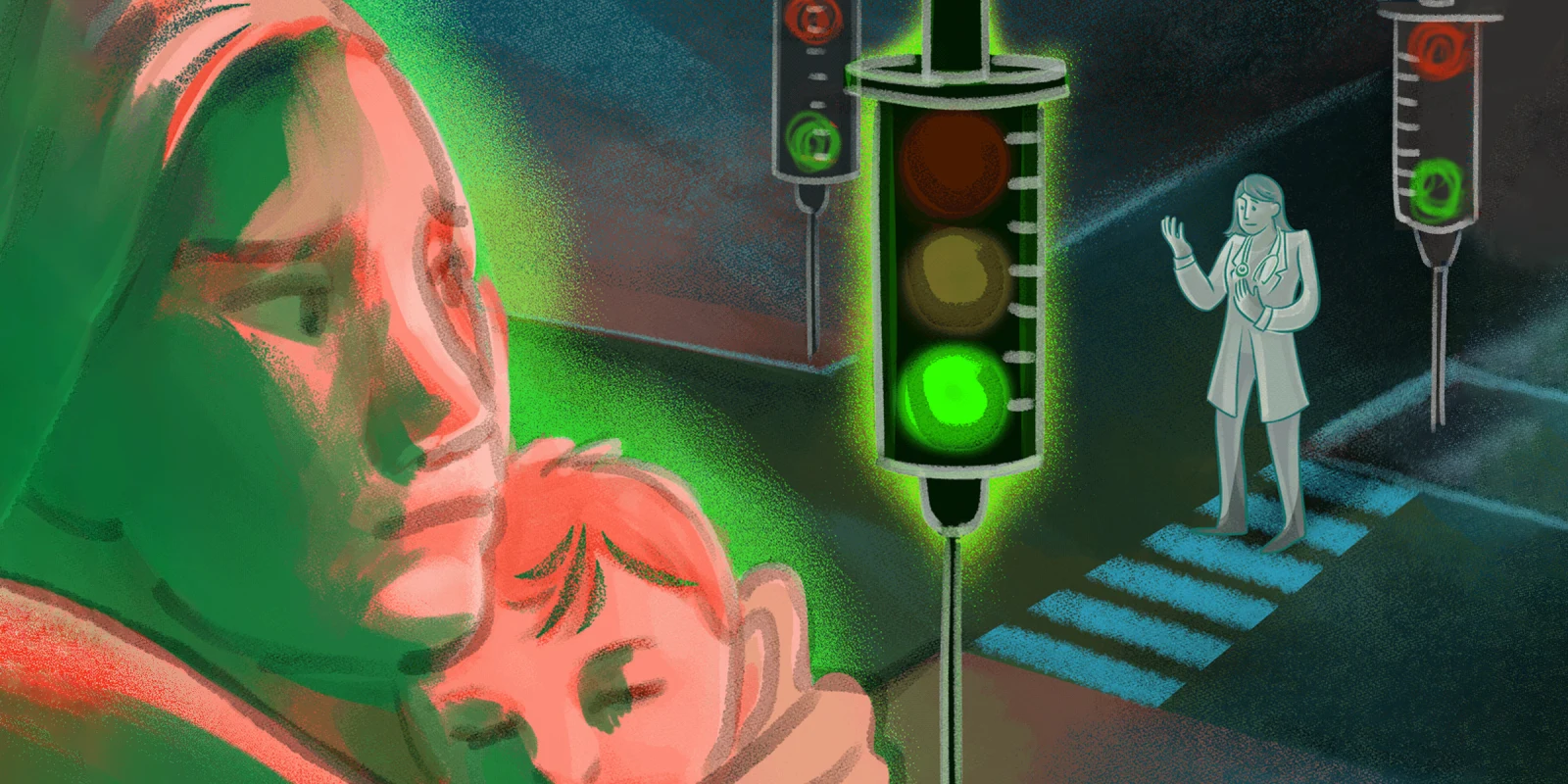

Illustration by April Brust