I dodged back to his room after noon conference ended. He had the perk of being in a corner room but he was too far gone to appreciate the light streaming through the window, sunbeams out of reach of the hospital bed, which was shrouded in shadow.

I dodged back to his room after noon conference ended. He had the perk of being in a corner room but he was too far gone to appreciate the light streaming through the window, sunbeams out of reach of the hospital bed, which was shrouded in shadow.

“I just removed his breathing tube a few minutes ago,” his nurse said quietly as I marched in.

I just wanted to ensure things were moving smoothly – that he was as comfortable as he could be for whatever time he had left. I didn’t intend to stay longer than necessary.

His chest was no longer reliably rising and falling. His breath was as ragged as he was – hair matted, skin swollen and bruised, eyes fixed on the ceiling unblinkingly. It was a pitiful sight, one I’d seen before. While I regretted that no family stood vigil next to him, I also knew how painful this may have been for them to see.

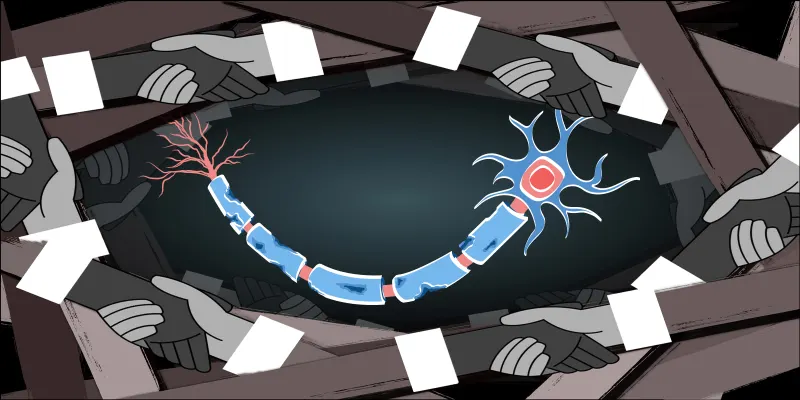

He’d arrived with impressive head injuries over a week before. While he was initially stable in the emergency department, he rapidly developed symptoms of lethargy and was found to have a massive brain bleed. Despite surgical intervention, his injuries were devastating and an ethics committee had decided to stop life-prolonging treatment after a week-long search for both improvement and family.

“We should go ahead and call the chaplain,” I told the nurse. The monitor bleeped with his rising pulse: 80, 90. Minutes to hours, I thought to myself. I’ve always appreciated the grey zones in medicine, those periods when nothing is absolute. The end-of-life has always felt like a grey zone to me. You can never predict just how long someone will make it.

A guard shuffled from the corner of the room, trying not to get too close. “Is he … ?” He made a slicing motion at his throat. His avoidance of the word “dead” seemed less jarring to me than the slicing. It felt crude and unnecessary.

“Not yet.”

He retreated back to his couch and his phone. I wondered who he could be texting.

I stood with my patient as his breaths became more shallow, as his heart began to slow. 80. 70. 50. Minutes passed, but it felt longer. The chaplain wandered in as his respiratory rate hit just five or so. He took his last breath as the last rites began. As the chaplain proceeded along the familiar words, I wondered if my patient had been a religious man. We turned off the monitor when the beeping of the alarms grew constant. It wasn’t long until I called time of death.

The guard wandered back in again. The commotion at the bedside had apparently renewed his interest. “So that’s it then?”

I felt anger welling in me, but I couldn’t quite place why. “Yes. Time of death 13:42.” I wanted to chastise the guard for fiddling on his phone instead of bearing witness to this man who was dying surrounded by strangers. I didn’t know my patient’s past, but surely we all deserve a moment of recognition when we pass. This was one aspect of end-of-life that wasn’t grey to me. No one should die alone.

Later I spoke with the medical examiner. I recounted to her the laundry list of injuries documented on arrival – cervical fracture, jaw fracture, orbital fracture – all head and neck. She asked if a cause for the injuries was identified. “Per report on arrival, the prisoner spat at a guard, who retaliated.” There was nothing grey about that.

Astrid Grouls, MD was an internal medicine resident in Houston,Texas when she wrote this piece, and is now a fellow in palliative and hospice medicine. She enjoys ethics, medical history, painting, cooking, snail mail, and spending time with her cat.

Image by VICTOR TORRES / Shutterstock