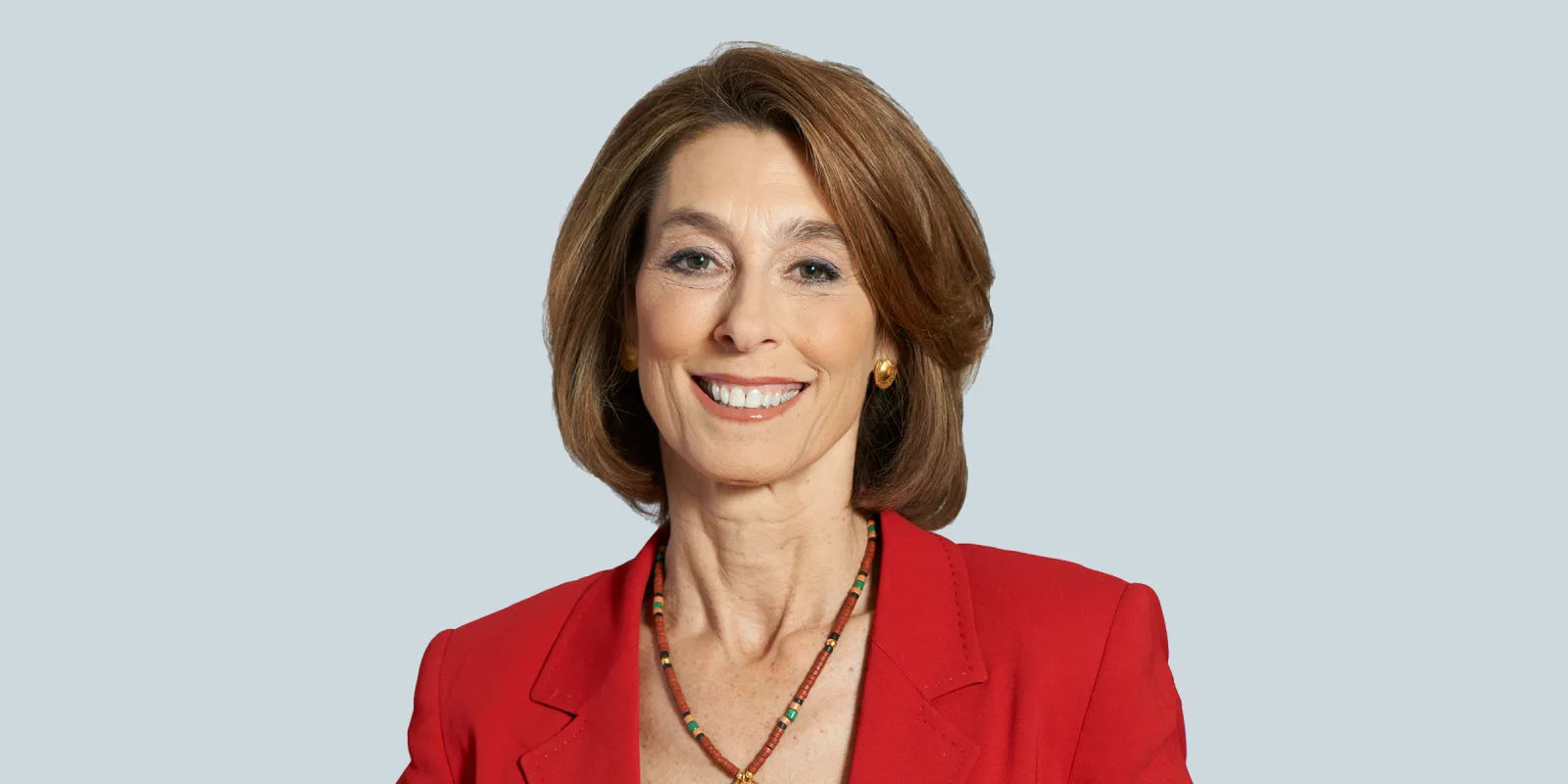

Dr. Laurie Glimcher is no stranger to forging her own path. A renowned immunologist, she became the first woman to serve as a dean of Weill Cornell Medical College of New York in 2012. Today, Dr. Glimcher is the first female president and CEO of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, the cancer research juggernaut. She’s also a mentor and role model for young researchers and for women in medicine.

Dr. Glimcher began her career as she was starting a family. “I will never forget when I became an instructor, even though I was supposed to be a full-time rheumatology fellow,” she said. “I had already gotten an R01 grant. I was 30 years old with two kids under three, and my first husband was a surgical resident. I was supposed to be seeing patients full time, and I also started my own little lab. It was probably the most exhausting time in my entire life. They were undoubtedly tough years. But you have to be an optimist to be a scientist, because a lot of things are going to fail, but ultimately some might succeed.”

Her commitment to her family and her profession were unwavering. She appreciated a quip from the former congresswoman Patricia Schroder upon being asked how she could be both a congresswoman and a mother. “I have a brain, I have a uterus, and they both work,” Rep. Schroder retorted.

“Having a high-intensity career while raising young children forced me to be unbelievably organized and highly efficient,” Dr. Glimcher recalled. “I would sit in the midst of the kids with the dog on my lap in the family room, writing a grant while they were talking and laughing and interrupting me. You have to have a huge passion for what you're doing.”

She was fortunate enough to have support from her nearby parents. “I wanted my kids to know that you can do this all. I wanted them to work hard and be really passionate about what they do and help people in one way or another. My daughter is a lawyer who was at the FDA for several years, my oldest son is a thoracic surgeon at Mass General, and my younger son, Jake Auchincloss, represents Massachusetts’ 4th Congressional District.”

Removing barriers for women in medicine is a passion of Dr. Glimcher’s. As a dean at Weill Cornell, she established a childcare center, paused the tenure clock for new parents, and instituted a paid parental leave policy. “Childbearing years intersect with early career, arguably the most difficult part,” she said. “I have spent quite a bit of time making sure that we put our money where our mouth is by providing more support for childcare needs. Why should women have to sacrifice their career when they decide to have a family? We need to make it easier for them to have both.”

In her own labs, she raised funds to create a program to provide postdoctoral fellows or graduate students who had primary childcare responsibilities with a technician to help with their experiments. “It makes a huge difference,” she said. “You don't always have to be doing the experiment yourself, right? If you want to go to a 5 p.m. junior league game to see your son or daughter, you’ve got the support of the technician who can keep the experiment running for you.”

In looking back on how she’s gotten to where she is today, Dr. Glimcher gives three main pieces of advice. One: Have an enormous amount of self-confidence. “Even if you don't feel self-confident, pretend that you do,” she said. “Don't give up, be stubborn. Figure out what you have to be a perfectionist in and what you don't. The data have to be incredibly rigorous and robust. They have to be 100%, but there are a lot of other things that can be 95%.” Two: If you have a family, hire people to help out if you can. “Get a housecleaner, get somebody who might make meals for you so that you can spend time with your kids. And don't worry if the sheets aren't folded.” Three: Stand up for yourself, especially if you’re a female physician. “You can be as demanding as your male colleagues are,” she said. “Don’t be afraid to speak the truth to people that are senior to you. Or to say, ‘I’ve gotten X number of grants, I’ve been really successful, and I'm an associate professor. I think you could increase my salary more. I'm ready for you to promote me to an associate professor. Here's my CV.’”

While health care can claim more gender parity than many other industries, there’s still a lack of representation for women in the C-suite. “I've been in countless meetings where I've been the only woman at the table,” observed Dr. Glimcher. “We need to focus on mentoring, recruiting, and supporting more women in science and leadership. Right now is an amazing time for science, particularly for cancer research. We can't afford to lose 50% of the brainpower of the workforce.” She suggests encouraging girls to pursue math and science fearlessly. Mentorship is critical, and it needs to continue as they progress through their careers.

There are a few qualities that a successful mentor should have, according to Dr. Glimcher: availability, critical feedback, and emotional support. When she ran a large lab, she met with her mentees individually every week. “I would not have more than 12 or 13 postdocs or graduate students so I could keep to that schedule,” she said. “It meant a happier lab and the people who needed help could get it.”

Dr. Glimcher thinks it’s important for mentors to be truthful when giving feedback about performance. Not every graduate student is going to end up running their own lab, and there are many other career options for scientists, like communicating about science or working in industry. “If somebody comes to you for advice on a career in academia or industry, you need to say they really have everything it takes, or they’re going to have a hard time because of their writing skills or efficiency,” Dr. Glimcher advised, “I think you owe it to them to be honest.”

Now at the helm of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Dr. Glimcher spends far less time in her laboratory. While she still considers herself a scientist, the majority of her time is spent on administration duties. “You have to know when you're ready to make that transition, to be able to put the institution's needs first,” she said. “And if you don't really take great pleasure in watching young people succeed, then you shouldn't be a dean or a CEO. When I pick up a science magazine and one of my former mentees has authored a great piece of work, I get as much satisfaction — if not more — as when my own lab publishes a paper.”

What mentor/mentee relationships have helped shape your career? Share your thoughts in the comments.

Which women in medicine would you like to read about? Share your suggestions or nominate someone.