Dara Baker is a 2020–2021 Doximity Research Review Fellow. Nothing in this article is intended nor implied to constitute professional medical advice or endorsement. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views/position of Doximity.

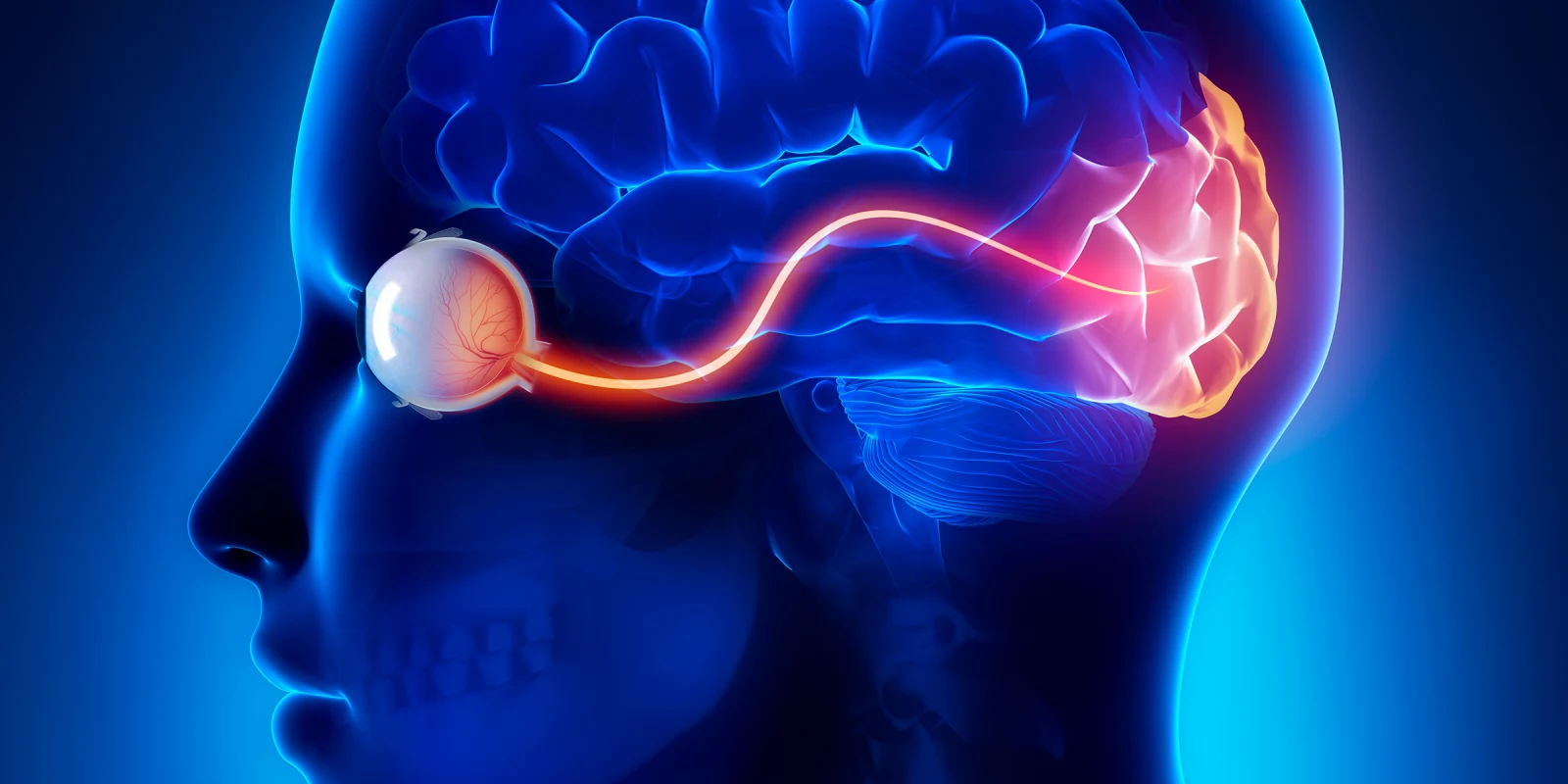

For thousands of years, certain types of blindness have been considered completely irreversible. However, recent breakthroughs in optogenetics, a neuroscientific technique that utilizes genetic therapy to control activity in specific brain cells using light signals, may soon improve the prognosis for patients with blindness.

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is one of many inherited retinal diseases that cause progressive blindness through loss of photoreceptor cells. It affects millions of people worldwide and yet, with the exception of a genetic therapy targeting an early-onset version of the disease, treatment is not available for most patients.

Recently, Jose-Alain Sahel and colleagues pioneered a method for stimulating previously defunct visual pathways using optogenetics. Specifically, Sahel et al. engineered a medical device — goggles — to translate objects into photopic pulses that, when applied directly to retinal cells, essentially perform the work of lost photoreceptors. By targeting retinal ganglia cells with an adeno-associated virus carrying the ChrimsonR protein (which responds to amber light), the investigators were able to induce expression of the protein in vivo and gain control of the neuronal pathways.

In the clinical trial investigating the safety and efficacy of this new therapy, the trial subject had been diagnosed with RP 40 years prior and had reduced visual acuity to light perception. The experiments were designed to compare monocular and binocular vision, with and without stimulation by the goggles. Additionally, visual therapy was instituted for seven months to rehabilitate the patient’s perception abilities.

Stimulating the patient’s monocular vision resulted in significant improvement in the patient’s ability to locate and perceive the structure of tested objects, as compared to unstimulated monocular or binocular vision. This finding was supported by EEG results, which demonstrated electrical activity in the region of the visual cortex corresponding to the stimulated eye, as well as by the patient’s subjective report of improved sight.

Overall, these results suggest that combined genetic and technological therapy for RP offers a novel method of addressing a previously insurmountable medical problem. More broadly, this approach may pave the way for the development of other joint therapies for other degenerative human diseases.

Dara Baker is a fourth-year medical student at GW SMHS, returning from her yearlong fellowship at NIH as part of the Medical Research Scholars Program, 2019–2020. She is an aspiring physician-scientist, excited about research in stem cell-based medicine, immunology, small molecule regulatory pathways, and genetics.

Image by CLIPAREA l Custom media / Shutterstock