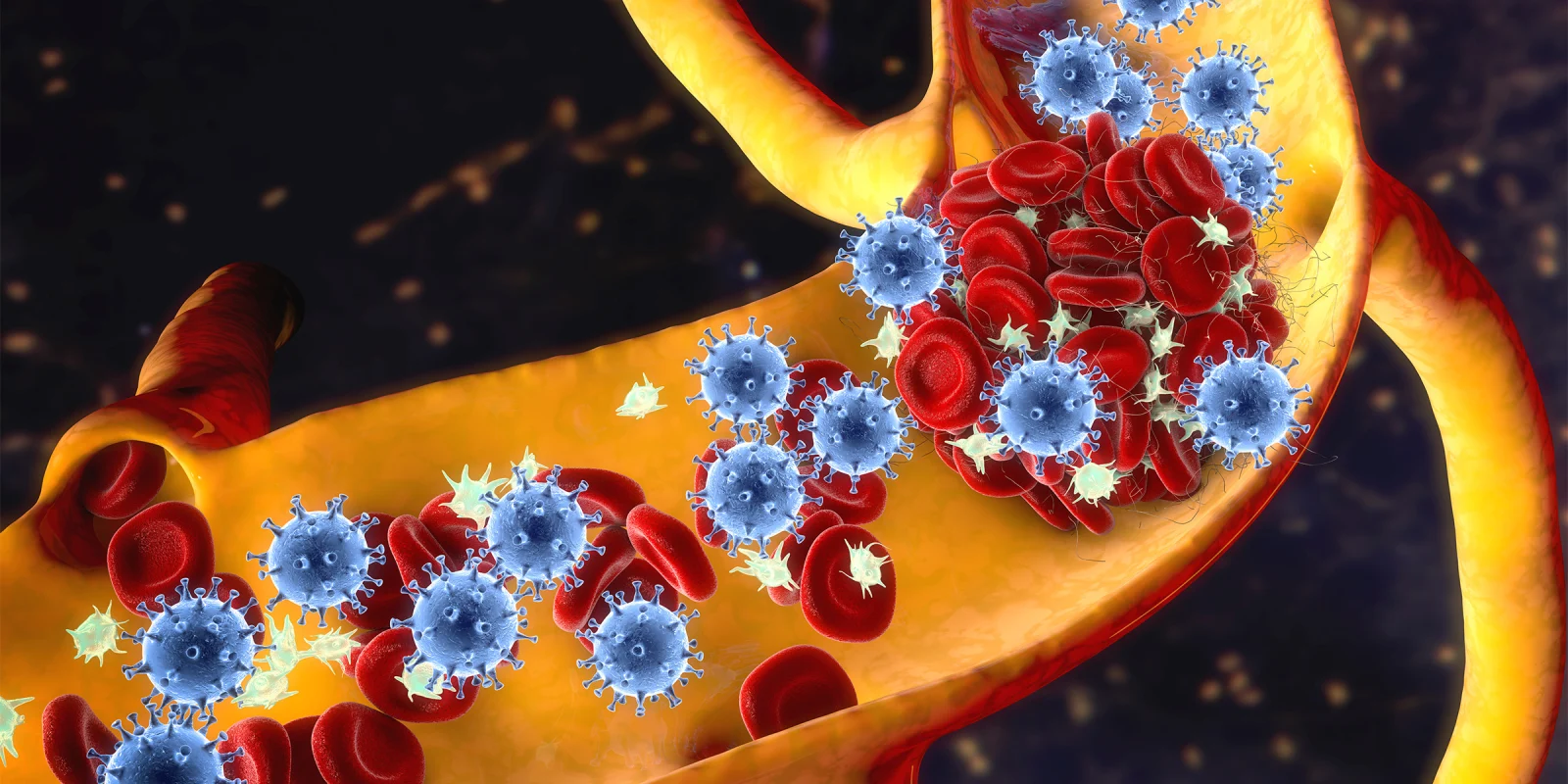

For the last 18 months, we have been struggling to understand the role of anticoagulation for patients suffering from COVID-19. Now, it is evident that COVID-19 is significantly associated with hypercoagulability. Increased incidences of macroscopic clot formation have been found in the form of DVT, pulmonary embolism (PE), and arterial thrombosis. Simultaneously microscopic thrombosis is also acknowledged. Unfortunately, what kind of treatment strategies should be obtained for microscopic thrombi in the absence of macroscopic clots is debatable.

Two recent multi-platform randomized controlled trials were published in the New England Journal of Medicine in August 2021. In critically ill patients, with COVID-19, defined as anyone required high flow nasal cannula oxygen, noninvasive ventilation (CPAP/BIPAP), vasopressors or mechanical ventilation, an initial strategy of therapeutic-dose anticoagulation with heparin did not result in a greater probability of survival to hospital discharge or a higher number of days free of cardiovascular or respiratory organ support than did usual-care pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis. On the contrary, in non-critically ill patients with COVID-19, defined as no requirement of any organ support, an initial strategy of therapeutic-dose anticoagulation with heparin increased the probability of survival to hospital discharge with reduced use of cardiovascular or respiratory organ support (4% adjusted risk difference) as compared with usual-care thromboprophylaxis. This difference persisted irrespective of the D-dimer level. The risk of bleeding was not significantly different in the two groups, below 2%.

It is important to note that the advantage in non-critically ill patients was found with heparin but not with newer oral anticoagulants like rivaroxaban. In the ACTION trial, in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 and elevated D-dimer levels, in-hospital therapeutic anticoagulation with rivaroxaban or enoxaparin followed by rivaroxaban for 30 days did not improve mortality or other meaningful clinical outcome and increased bleeding compared with prophylactic anticoagulation.

A similar advantage of heparin was not found for the primary outcome of a composite endpoint of adjudicated venous or arterial thrombosis, need for ECMO or mortality in 30 days was not found with intermediate-dose anticoagulation strategy compared to standard thromboprophylaxis in another randomized controlled trial known as INSPIRATION trial.

These studies raised several questions. Proposed questions and speculated/hypothesized (not scientifically proven) answers are as follows.

- Why did Heparin AC work for the non-critically ill but not for the critically ill?

One speculation is that in critically ill patients, it is too late, and interventions are not likely to work. Also, in critically ill (possibly later in stage), clots are organized, and not possible to improve with therapeutic anticoagulation. Therapeutic anticoagulation may cause more harm during that stage than help.

- Why was the positive effect seen with heparin only but not with novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) like Rivaroxaban?

Heparin does have possible antiviral and anti-inflammatory action, which NOACs do not have.

- How long was the anticoagulation continued in non-critically ill patients?

In the study, therapeutic anticoagulation was continued up till 14 days or till discharge or till one day after oxygen requirement was no longer present.

- What should be done if a patient was non-critically ill, started on therapeutic anticoagulation and then worsened, became critically ill, and required organ support?

In the original study, they continued therapeutic anticoagulation as the results of these studies were not available at that time. Based on the analysis of critically-ill patients, investigators advise stopping therapeutic anticoagulation if the clinical condition deteriorates.

Dr. Dalal is employed by Beaumont Health, he has no conflicts of interest to report.

Image by Kateryna Kon / Shutterstock