“Ok, sweetie, you’re going to feel a little bit of pressure.” In retrospect, I found this statement to be laughably under-representative of what was about to happen to the woman lying on the operating table in front of me with a sea of blue drapes encircling the object of our interest: her stomach.

I was standing, legs shoulder-width apart, hands buried up to my knuckles in this woman’s suprapubic incision, grasping at the slippery fat along her abdominal wall, her blood coating my gloves. On the word “pressure” it was my cue to pull, to sink my weight into the floor and use all of my strength to tear this woman’s abdomen apart.

It ripped. A quote from MacBeth describing a cesarean section immediately entered my head: was from his mother’s womb untimely ripped. I shuddered at Shakespeare’s acuity, though the flesh and blood in front of me were the reason I had left a career in theatre for medicine. I had craved real people over characters, wanted to witness real human experiences, trade in words for action, and assist the human experience in a tangible way. But this particular view lent a whole new definition to Operating Theatre.

This was my first day of my first clinical rotation. It was the evening of July 4th and within 5 minutes of arriving at the OB ward I was delivering a placenta as fireworks blasted outside. Now it was 2 in the morning and I was entering my first C-section.

This particular case was upsetting to me. I had triaged this patient. She was friendly and funny and made me laugh. When asked who would be with her in the C-section she had stated the child’s father, adding darkly, “or he better be. I will kill him if he doesn’t show up.” And she had waited, patiently, for him to come. And he had not. And breathing heavily, begging the OB team for a few more minutes to stall, we wheeled her back to the OR unable to wait any longer. Her baby was breach and had proceeded to decelerations on the monitor. And he still hadn’t come. And she was alone in this struggle with no one to hold her hand or comfort her besides us.

The anesthesia team administered the potion which placed her into a semi-daze. With the first cut of the knife she winced, saying she could feel it. I felt dizzy. More drugs flowed through her IV. The scalpel sliced skin, fat, fascia, and mucosa horizontally above her pubic bone. It exposed the rectus abdominus muscle. Then my hands were on the side of 5-inch incision and she was being called “sweetie” and I was being told to pull with all of my strength. She moaned loudly. I gritted my teeth because I hated that she could feel anything and hated more that she had no idea how little she felt compared to what it looked like.

I yanked apart her body, sacred in its ability to serve as life force for herself and this unborn being, butchering it like an empty carcass now discarded to expose the uterine sac underneath.

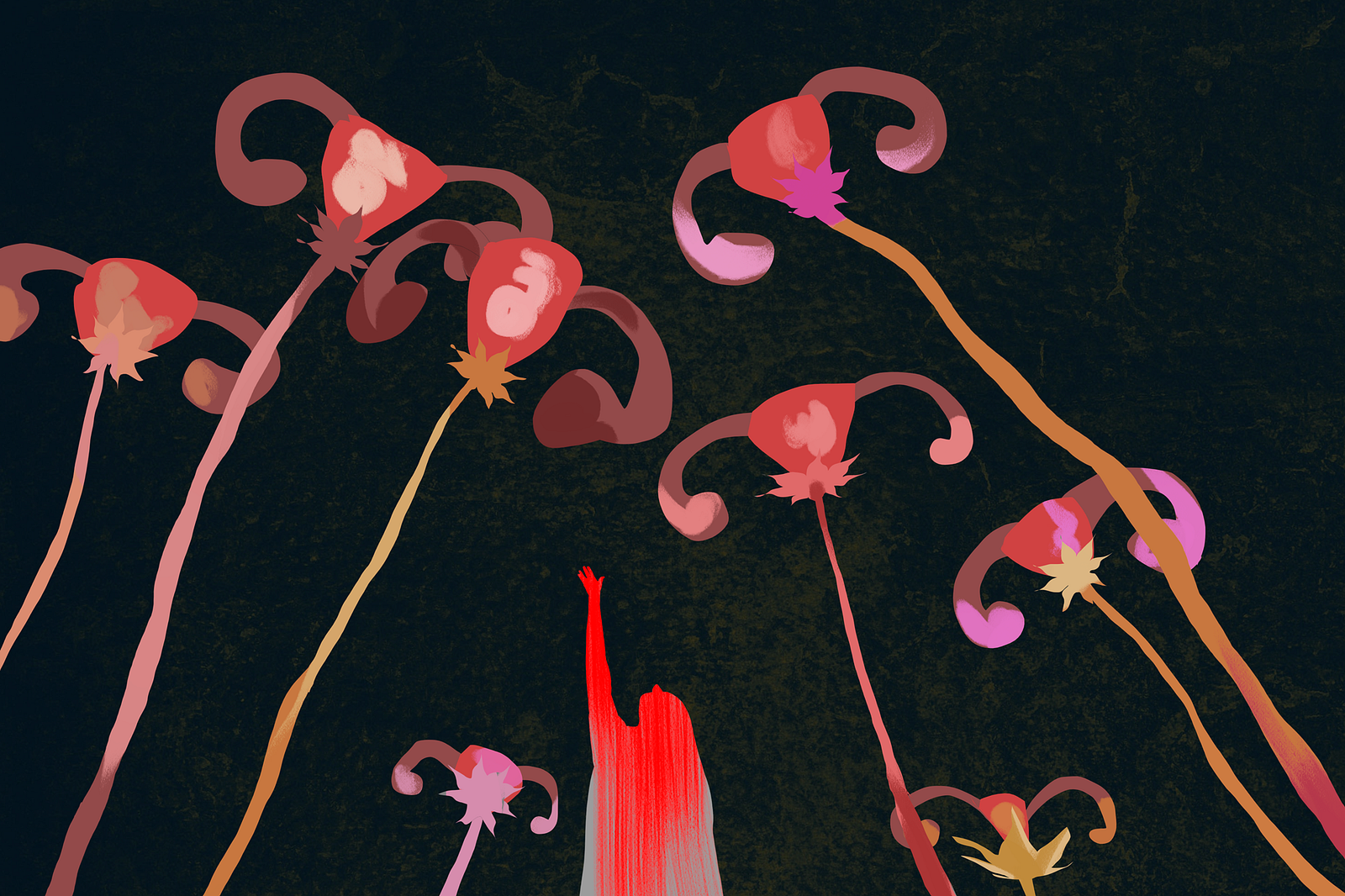

I thought about how unfair the female experience is. Biologically we, as half of the species, were disadvantaged from the beginning of time, sacrificing our bodies to gift human life to this planet, dying to preserve our species. Men would subsequently treat women inferiorly for millennium, often citing the female body’s miracle-making capabilities as an excuse for why. But looking at this woman splayed in front of me, it was clearer than ever that they missed something key: the power within a woman, her strength, power, and resilience.

The patient had sunk to a primal place within her moans as her body performed the miraculous. In the center, like a sacrificial act to humankind, we circled her, all women, physicians, nurses, techs, completing the sterile séance blending medicine with nature. Like the end of a dance, she opened like a chasm, her innards exposed and glistening in front of us.

I slipped aside. The resident sliced across the uterus, and the amniotic sac erupted splashing up like a fountain. The resident’s hands were inside grasping onto the slippery form, and pulling it out from its depths onto the mother’s stomach. Suctioning the nose and mouth elicited a cry.

“Is he crying?” the mother asked groggily. “I can’t hear him, is he alright?” We assured her he was robust, and from behind that blue curtain I heard the anesthesiologist comforting her as best she could through the barrier of a surgical mask, promising she would get to see him soon.

The mother was sewn back together, piece by piece and was handed her final part, the child. She gazed at him with an immediate bond so intense I couldn’t stop looking. It was a display of pure emotion. It was a look which completed an intricate and complicated puzzle of pain, love, and hope. It was a look which a thousand actors I know would do anything to be able to achieve on stage. But this was life, not the mimicry of it.

Thinking back on my first clinical night, it would stand like a Fellini film in my head with whirling colors and the musical lilt of labored screams, the characters all basted in fluid spilling from every orifice, mingling sweat, secretions, saliva, and tears. But this woman would stand out. She would insist upon a place in my memories like the heroes of plays and books I looked to in an effort to explain the intricacies of humanity. She would imprint on me her emotional complexity and physical capability and force me to appreciate the human spirit in a new way.

Lauren is a 4th year medical student at Georgetown University, SOM. She had a career in theatre before switching to medicine, and still enjoys writing, acting. and all things art in her spare time.